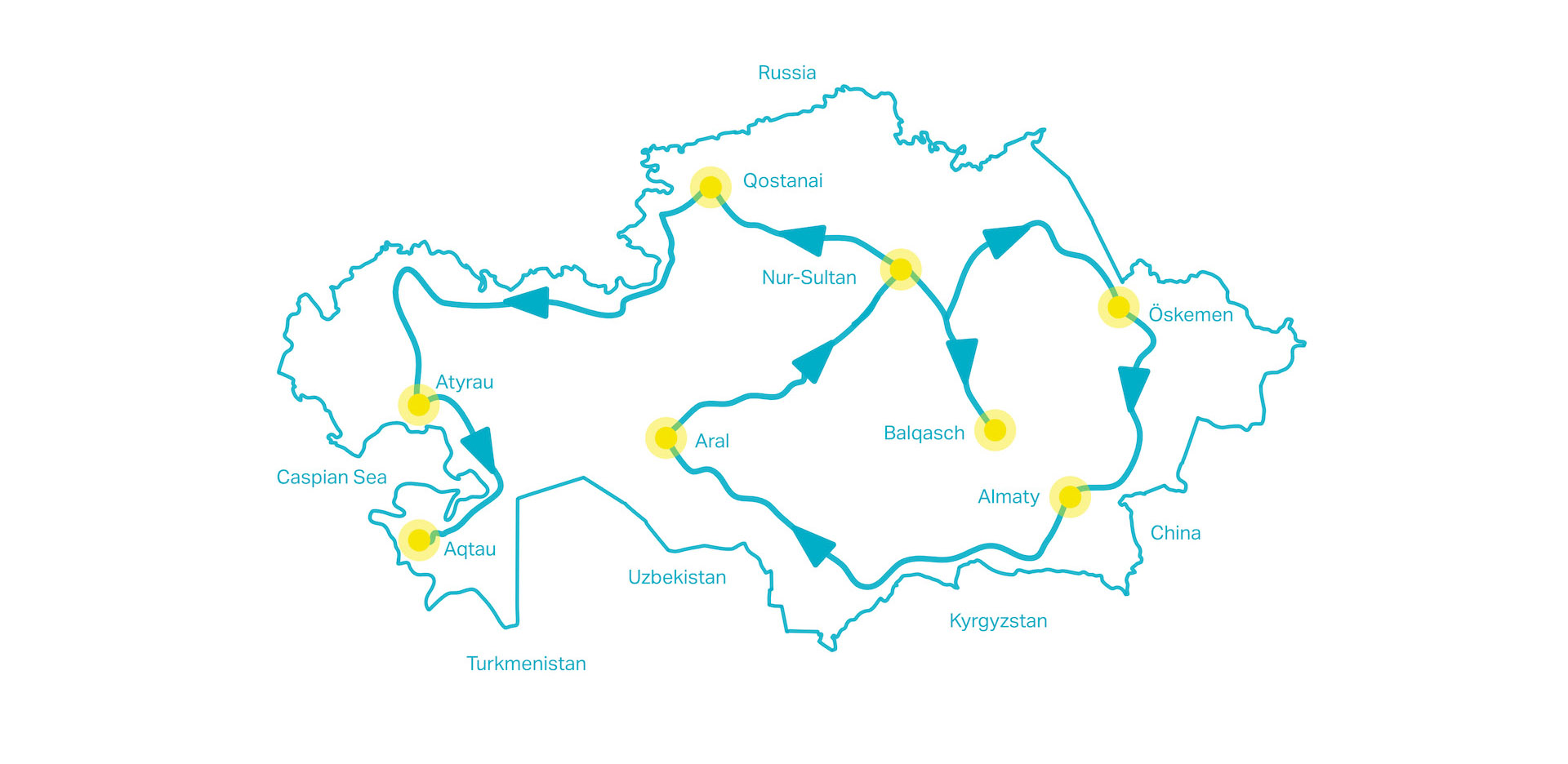

In advance of the 30th anniversary of the independence of Kazakhstan from the former Soviet Union, Mario Heller took a 7,500km train journey around the country spending 225 hours over 16 days on Kazakh railways.

The monotonous rattling of the train travelling straight ahead accompanies us through the steppe of Central Asia. The air that travels with us smells of cooked food and the exhalations of dozens of passengers. Sounds drift over to me from various corners of the wagon: A sawing snore, children’s screams, folk music and a hyperactive radio voice, just across from my neighbour. Lying in my upper bunk bed, I seek body contact with the cooling plastic wall because of the summer heat. I am in a twilight state between shallow sleep and nervous glances at my mobile phone: still no reception.

I am trapped in the here and now. It is shortly after three in the morning. A few lights glide past the window, otherwise, it is pitch dark. It is the beginning of my almost three-week train journey across the endless expanses of Kazakhstan. Shortly before midnight, I board the night train in the former capital Almaty. At my side is Daulet as a translator for this expedition. The 26-year-old, well-fed Kazakh works for the country’s Geographical Society. I met him on Facebook only a few days ago. His sedate, almost phlegmatic manner has sedated me since our first meeting and gives me a sense of

calm. Daulet’s response to suggestions of all kinds: “Yes, why not? That’s how we do it.” Now he lies in his blue work jumper in the bunk bed across from me, snoring to himself. Outside, a whistle sounds, newly arrived passengers prepare their night’s lodging, and the train starts up again. We fall back into our monotonous rhythm. Gradually, sleep overcomes me, despite all the unfamiliar sensory stimuli.

A group of young people talk and share food and drink on a long distance train sleeper carriage. Over half of Kazakhstan's population is under 29 years old.

A view of the train tracks and the steppe landscape close to Kulsary.

A few weeks before, I was looking at a map of Kazakhstan and wondering how to get around in such a vast country. I soon found out that the state railway company is the country’s largest employer, with 146 000 employees. Nevertheless, the railway network is only 16 000 kilometres long – far less than in Germany, although the area of Kazakhstan is the same as Central Europe. The majority of the country consists of vast plains, sometimes merging into hills, and almost half is covered by sand or gravel deserts.

The only mountainous area is in the south-east, where the Tian Shan mountain range runs along the border with China and Kyrgyzstan. The snow leopard, Kazakhstan’s national animal, lives in the spruce forests. Among the country’s 48,000 lakes is the Aral Sea, which has almost dried up. It represents one of the greatest environmental catastrophes of the last decades, caused by the large-scale cotton cultivation during the Soviet era.

The following day I feel as if the ceiling of the wagon has fallen on my head. It is already light outside, and the steppe passes by continuously. I lazily roll out of my bunk bed and climb down. A few

fellow passengers are already waiting for me there, eyeing me curiously. Foreigners are a rarity on Kazakh trains. On my 7500-kilometre journey, I will meet only three western travellers.

Vegetarian probably, like all Europeans!

In the last carriage corridor, we meet Mayra, a 52-year-old woman who invites us into her compartment with an infectious laugh. Her friendly face and her esprit sweep away my tiredness. She offers us boiled meat from a plastic bag, which I gratefully decline. “Vegetarian probably, like all Europeans!” Mayra screeches indignantly and amusedly at the same time. “You can’t even defend yourself if you don’t eat meat.

Kazakhs are born to be warriors; that’s why they eat a lot of meat!” she explains and promptly challenges me to an arm-wrestling match. I accept the duel – not out of ambition, but out of friendliness – but must quickly admit defeat despite an honest effort. “Don’t take it so hard; we’ve already beaten the Germans once!” she calls cheekily with a wink and reaches for a piece of meat with her fingers again.

In Kazakhstan, food plays an important social role. In the train compartment, food is constantly shared between passengers, which is considered a sign of respect and hospitality. Tupperware, cups and pots are piled up on the small tables. Outside the windows, the monotonous steppe passes under a milky sky. “On a train journey, your thoughts are completely free,” Mayra explains and leans back with pleasure.

Even as a child, she was oIften taken along by her parents when another family reunion thousands of kilometres away. “In the past, there was a community between travellers. People shared their secrets with strangers. I started pen-pal relationships with some people; some continue to this day. Today, most travellers lie there like mute fish, staring at their smartphones 24/7.”

A woman watches a film on her phone during a long train journey while another woman in the compartment sleeps. In the small train compartments called Kupe, four complete strangers are brought together in the smallest space on each journey.

A police sniffer dog on a train shows its teeth during a search. Police check long distance trains in Kazakhstan on a regular basis, especially in areas with high crime rates.

Hot water is poured from a large urn to make tea in the restaurant carriage of a train.

Only on the lines between the retort capital Nur-Sultan and Almaty do newer express trains run. These are quite respectable next to the Swiss railways, and even the older trains are characterised by great comfort and high punctuality. Each carriage is equipped with three toilets and a kitchen, including a microwave. There is a

colossal water boiler in the corridor that can make tea around the clock – or Korean noodle soups, which are very popular among passengers. At least one train attendant supervises each wagon. Their tasks go far beyond checking tickets. As we are on our way to the capital Nur-Sultan, we meet the train attendant Marat.

Marat (63), a conductor, stands beside the train.

We interrupt him while he is washing up in the kitchen, and he asks us to come into his cabin for a chat. It is cramped and only suitable for sitting or sleeping. On the wall hangs his neatly decorated uniform, which Marat proudly puts on for our conversation. “My grandmother worked as a train conductor. As a child, I was sometimes allowed to ride along and watched her work with fascination,” the 63- year-old says excitedly. For 30 years, the moving trains have been his second home. Marat explains that he never feels homesick on the journey itself. For train conductors, he says, home lies in the constant movement. “Every time I leave my family behind, I know that someone is waiting for me. Being away from each other makes the bond between me and my family’s hearts grow even stronger.” A little later, the train pulls into the station with screeching brakes. Marat squeezes between the passengers who want to get off and opens the door. He helps them get off and then stands proudly in front of the train. Sometimes he feels like a psychologist, Marat says. You have to understand the passengers. Some are happy, others sad. Sometimes you have to give people advice. Sometimes you just have to listen and keep quiet.

A benevolent nature is a prerequisite for this job. But Marat never stops learning: “Sometimes I think I’ve already seen everything and then I’m surprised again. A few years ago, an older man fell off his bunk bed in the middle of the night and broke his hand. I bandaged his hand with cardboard, let him sleep in my cabin and accompanied him to a doctor the next morning at the first possible stop. There have also been women who have given birth to their child on the journey.”

Marat waves the smoking men on the track next door back into the train carriage. He is actually from Turkmenistan; shortly before the USSR collapse, he moved to Kazakhstan, together with his ten siblings. Soon he will retire. He doesn’t know what he will do yet: “Time will tell. With my nine children, eight of them daughters, it will hardly be boring,” he says with a smile and walks away.

Each terminus tears apart the moments experienced together. As the beginnings of the city of Atyrau slowly glide past the train windows in the early morning, drenched in golden sunlight, the mood in the carriages is already one of departure. All passengers neatly fold their bedsheets and blanket covers and press them into the train attendants’ hands. The compartments are left exactly as they were found. When the train finally stops, the last friendly looks are exchanged, and the passengers disembark. In Atyrau, we become spectators of a unique

spectacle: a crowd of people of all ages has gathered around the wagon. A newly married couple is returning home from celebrations. Excitedly, the waiting family members clap their hands; confetti flies through the air. The disembarking couple is congratulated with countless heartfelt hugs. Kazakh weddings are highly formal celebrations that follow strict, centuries-old traditions and last for several days. For our journey, stopovers are rather inconvenient – we usually rest for about twelve hours in run-down hotels near the stations before boarding another

train. Most of Kazakhstan’s cities are not particularly attractive. The former capital Almaty with its great cultural offer, is still the favourite city even among the locals and is also always the country’s economic centre. It is also extraordinarily green and surrounded by breathtakingly beautiful mountain scenery. Nur-Sultan, on the other hand, the capital, recently named after the recently deposed president, looks more like the playground of a megalomaniac despot: In the middle of the desert, futuristic buildings are lined up with dilapidated prefabricated buildings.

A long distance train waits on the platform to begin its journey. Most long-distance journeys in Kazakhstan begin and end in the former capital of Almaty.

Foreigners are rarity on Kazakh trains. On my 7500 kilometre jounrey I will meet only three western travelers.

A young woman walks along rusty train tracks in the Aral Sea region of Kazakhstan. The Aral Sea is one of over 48,000 lakes in Kazakhstan. It is almost dried up as a result of large-scale cultivation of cotton during the Soviet era.

Adylet (83) in winter clothing poses for a portrait in a train carriage.

The country’s fascination lies in the many scenic highlights – which we unfortunately only see passing by the window. At the railway station in Aralsk, an unusual figure catches my eye: An older man with a long white beard, grey coat, and black fur hat stand out clearly from the rest of the passengers on the platform. He is travelling alone with a massive suitcase that he is laboriously dragging along behind him. No sooner has the train departed than I set off with Daulet in search of the man. We find him in the second to last carriage and sit down opposite him and introduce ourselves. What happens then surprises not only the two of us but probably the whole carriage: the man starts talking without Daulet having to ask him a question. His statements are somewhat disorganised and confused – again and again, he slips in quotes from Kazakh philosophers – but by no means uninteresting. “Anyone who still mourns the Soviet Union today is out of his mind! There were no freedoms then; society was godless and lived under constant brainwashing,” he preaches angrily. The people on the train are all silent and stare at him. His whole body sways rhythmically back and forth as if he were saying a prayer. “When the Soviet Union was slowly crumbling, our family mostly ate only bread. We only survived because our ancestors had a farm built up through years of hard work! Today’s Kazakhs have all the opportunities, but all they do is complain all the time. It seems that hard work has been unlearned.” Today’s politics are not perfect either, and the outgoing president Nursultan Nazarbayev still promises, as he did 25 years ago, that the best times are yet to come. Still, at least now there is peace, open borders and enough food.

Three men talk and share food and alcohol on a train.

The mood in the Kazakh on-board restaurants is always cheerful. Peals of laughter and the smell of soup permeate the wagon, and the serving girls bring one bottle of vodka after another to the exclusively male guests. Three burly men invite us to their table. While Daulet plays the Muslim card to avoid drinking vodka, I settle for a few glasses. Before each toast, someone has to make a wish out loud. Smoked cheese and

salad are served with vodka. The three men quickly become affectionate, constantly wanting to shake my hand – and pouring me more and more. By the sixth glass, I’m shouting that we may all live happily and healthily forever. Daulet translates my wish, already slightly annoyed. Suddenly a young man at the table opposite intervenes and starts asking questions. What am I thinking, coming from prosperous Germany and spying on

the passengers here? My three new-found friends react with extreme anger and threaten to break his neck on the spot. A heated discussion ensues. Daulet tries to mediate and tells me again from the beginning why I am travelling through Kazakhstan by train. Before the mood ultimately tips over, we order our hosts a new bottle of vodka, as is proper, and leave.

Most long distance train journeys in Kazakhstan begin and end in the former capital Almaty. Late in the evening, the station is usually very busy.

A stall selling barbequed meat to train passengers at Khromtau station.

A long distance train with its lights on comes into Aralsk station in the middle of the night.

A man looks through a train window at night in Nur-Sultan, the capital of Kazakhstan.

Dina (79) sits in a train carriage by a table of food and drink. 'Certainly I have spent several years on Kazakh trains and made hundreds of acquaintances during my journeys. Now I am almost 80 years old. Although there are now affordable plane tickets, I prefer to travel by train. The time seems to stand still here. At my age, there is no hurry anymore and I fully enjoy these train rides.' 'Certainly I have spent several years on Kazakh trains and made hundreds of acquaintances during my journeys. Now I am almost 80 years old. Although there are now affordable plane tickets, I prefer to travel by train. The time seems to stand still here. At my age, there is no hurry anymore and I fully enjoy these train rides.'

Kamilla (19) stands in the train corridor. 'In Kazakhstan, it does not makes sense to follow politics. Everything is ruled by one man. I am concentrating on my computer science study in Nur-Sultan. This is the future of humanity. I am very privileged to be able to study in a good university. Compared to young people in Europe, we are maybe much less educated on average, but we are much more attached to our family and way more patriotic. I live in a typical Kazakh family. My parents think everything is good and we have to thank god for the great politicians and I often find myself debating with them.

As we are on our way back after more than two weeks, two particularly older women in a compartment catch our attention. Their faces show deep furrows. They move in slow motion but radiate inner contentment. Both women wear white headscarf. On the little table is a tetra pack of milk and a teapot. We sit down with them. Nubia is peeling an apple, which she, of course, offers to us immediately. Reyna sits cross-legged in her seat and looks at us curiously. Then the two women begin their story. Both are ethnic Kazakhs, but until eleven years ago, they spent their entire lives in Afghanistan: “We were among the children of

parents who were a thorn in the side of the Soviet state. People like us were appropriated and put in prison camps at that time. Our parents were aware of this and fled the country.” In Afghanistan, they grew up in Baghlan, near the Tajik border. The Kazakh community in Afghanistan today still numbers several thousand. An exact count is not possible due to the ongoing conflict with the Taliban. “Our parents taught us at home. We never had anything to do with Afghans ourselves; it wouldn’t have been possible purely in terms of language.” The two women returned to Kazakhstan together with all their relatives. When they set foot

on their homeland’s soil for the first time, they had mixed feelings. “Relief, joy and sadness were close together. We were finally home, but we had left all our friends and neighbours behind,” says Nubia. In the end, it was the right decision, Reyna reassures. Here in Kazakhstan, there is peace, and that is all you need at this age. Well, that and this train journey: “Travelling on rails is the most exciting adventure. You can drink tea all day, meet new people and watch the steppe from the train window. It enlightens my inner self,” Reyna concludes.

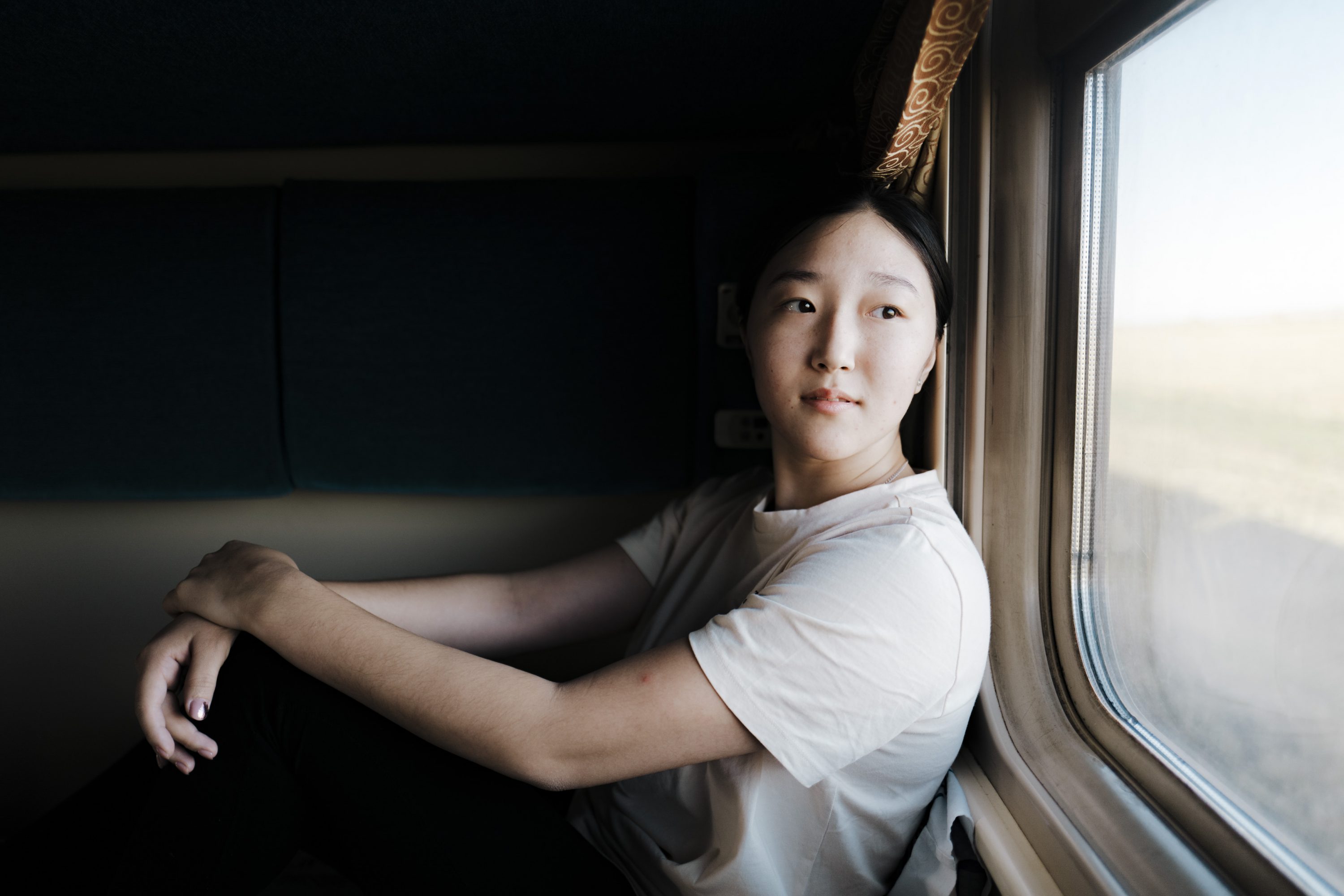

Aliya (20) sits by a train carriage window.

‘This train is now only a few stops from its destination. Most of the time the train runs on time, but every now and then it makes extraordinary stops, for example when people don’t live near a station. It’s the same in real life: you should always be ready to stop at the right time, even if it seems an unusual halt. There’s never a a direct route to your destination without stopping in between, just as a train never goes straight to the terminal.’

After two and a half weeks, we arrive back in Almaty late in the evening. In total, we have spent 225 hours on trains. Even nights later, I still feel as if I am gently rocked back and forth in my bunk bed on the train as we travel through the pitch darkness.