The Roots of Destruction

by Matthew Smith

Genocide is never spontaneous. It requires planning, coordination and decisions by people in power.

Above all, genocide takes time. It doesn’t happen overnight.

A dominant narrative about what occurred in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine State in 2017 suggests that the Myanmar army spontaneously attacked hundreds of thousands of ethnic Rohingya Muslims in response to militants who killed a dozen police officers on 25 August 2017.We now know that during the weeks and months before those Rohingya militant attacks, the Myanmar authorities made extensive preparations to commit mass atrocity crimes against indigenous Rohingya civilians.

The Myanmar authorities systematically disarmed Rohingya villagers, confiscating household items that might be used as weapons or in self-defence. Myanmar soldiers tore down fencing and other structures around Rohingya homes, providing a greater line of sight on those civilians. Soldiers trained and armed local non-Rohingya communities in Rakhine State—communities whose anti-Muslim animosity was carefully cultivated, effectively preparing them to kill their Rohingya neighbours, which is precisely what they did.

The government blocked both lifesaving humanitarian aid and access by aid workers to Rohingya villages, physically weakening the civilian population ahead of the attacks and removing monitors from areas where the military would later burn villages to the ground. Myanmar’s latest attempts to destroy the Rohingya unfolded as planned.

The ‘Rohingya crisis’ in Myanmar didn’t begin with these preparations. It didn’t begin when the ragtag militants killed those police officers on that fateful day in August or when Myanmar army soldiers and their extremist civilian subordinates brutally massacred Rohingya men, women and children in villages throughout northern Rakhine State. It didn’t begin when more than 800,000 civilians fled for their lives across the border to Bangladesh—weary, traumatized and, in many cases, bloodied

and wounded.

Rather, Myanmar’s destructive, genocidal steam engine started in motion towards the Rohingya decades ago. It was arguably

a speck on the international horizon in the late 1970s, inching closer and closer year after year, unmitigated, despite mounting evidence and warnings from the Rohingya themselves, human rights groups, journalists and others, until finally it rolled over the Rohingya with a dull and ferocious clamour in 2017.

And it continues to roll.

Most Rohingya do not idealize their past, but there was a time when they had access to full citizenship in Myanmar. There was a time when Myanmar society was not disputed; when the Rohingya ethnic identity was not contested, let alone rejected outright as it is today.

In 1977, when most Rohingya had equal access to full citizenship in Myanmar (when the country was still called Burma), the Myanmar military initiated operation Naga Min (Dragon King), ostensibly to scrutinize and ‘register’ residents of three states and two divisions—now called ‘regions’—in the country as either citizens or foreigners. It was a violent ‘census.’ The exercise eventually made its way to Rakhine State in February 1978, targeting the Rohingya. Strikingly similar to the most recent attacks, army soldiers razed entire Rohingya villages and raped and killed civilians, forcing more than 200,000 people across the border into Bangladesh.

Mirroring today’s rhetoric, the Myanmar authorities at the

time denied any allegation of wrongdoing, instead blaming the situation on ‘wild Muslim extremists’ and ‘rampaging Bengali mobs.’

News coverage was sparse but prescient: The Far Eastern Economic Review reported on 14 July 1978 that the attacks constituted ‘Burma’s brand of apartheid’ against the Rohingya and suggested the ethnic group ‘could well turn out to be Asia’s Palestinians,’ facing protracted statelessness and displacement.

The Foreign Minister of Bangladesh visited Myanmar in July 1978, and soon after, Myanmar President Ne Win agreed to repatriate the Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh. Bangladesh then forced back to Myanmar—specifically to northern Rakhine State—hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who had just fled their homeland.

Why would Myanmar support the coercive return of a group of people it had just attacked and forced out of the country?

This, too, turned out to be calculated.

Three years after the Rohingya refugees returned to Myanmar, the military government passed the 1982 Citizenship Law, stripping the Rohingya of their citizenship. Now the authorities could ‘prove’ the Rohingya didn’t belong in Myanmar, and they proceeded to use the legal exclusion to tack on a cascade of other violations and daily indignities against the Rohingya.

Overnight, Rohingya civil servants lost their jobs and pensions, and all Rohingya lost their nationality. General Ne Win described the controversial law as a way to ‘clarify the position of guests and mixed-bloods.’ He explained that ‘foreigners who had settled in Burma [Myanmar] at the time of independence have become a problem’ and that those who could demonstrate long-term residency would be given ‘associate’ citizenship under the law, which would still prevent them from obtaining any role in government, among other positions. Most Rohingya individuals would be denied even that status.

The 1982 Citizenship Law soon became the world’s most effective tool in creating statelessness. And Myanmar became host to more stateless people within its borders than any other country in the world.

As time would tell, the attacks of 1978 and the legal exclusion

of 1982 were precursors to another wave of violence in 1991.

Under the chilling names Operation Clean and Beautiful Nation, the Myanmar military embarked on additional ‘clearance operations’ against the Rohingya, now in the context of a counter- insurgency operation. The New York Times reported ‘tens of thousands of fleeing in panic from Myanmar.’

‘They are fleeing the Burmese army,’ the paper explained in February that year, ‘which, they say, is raping and murdering, forcing men into press gangs and destroying mosques and schools, all as part of the military junta’s program of making all things Burmese.’

When all was said and done, Myanmar had again forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh.

And, like clockwork, the process was put on repeat.

Working in collusion with Bangladesh authorities—who made it clear

they did not want Rohingya refugees on their territory—Myanmar military officials again forced the return of tens of thousands

of Rohingya to Myanmar, this time with the cooperation of the United Nations.

With a fresh batch of forcibly returned Rohingya, the Myanmar authorities once more implemented discriminatory policies against the population they held captive. Through a series of policies and orders, the government confined the Rohingya to villages, denying them freedom of movement. The government enforced restrictions on birth—an act of genocide—as well as restrictions on marriage and other aspects of daily life, such as repairing one’s home. The Rohingya typically construct their homes with bamboo and other natural implements and, given the drenched monsoon seasons and the scorching hot seasons

of Rakhine State, home repair is an essential task for any family.

Over the years, the authorities in Myanmar also went to great

lengths to fuel animosity between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists. The latter represent the majority population in Rakhine State and enjoy full citizenship, but they, too, have lived under the boot of the Myanmar military for decades, enduring

a litany of human rights violations.

Tensions between the groups reached a boiling point in June

and October 2012. Following the rape and murder of Thida Htwe, a young Buddhist woman, allegedly by three Muslim men, deadly violence erupted between the Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims and quickly escalated into full-scale targeted attacks

on Rohingya and other Muslims, such as the ethnic Kaman, throughout Rakhine State. Soldiers and civilians razed Rohingya villages and opened fire on anyone who attempted to extinguish the flames. Just as before, there were massacres, mass rape and mass displacement. When the violence finally subsided, Muslim villages in 13 of the 17 townships in Rakhine State were in ashes.

In the predominantly Buddhist areas of Rakhine State, the authorities herded masses of internally displaced Rohingya into dozens of internment camps, confining approximately 120,000 persons in poorly equipped settlements—a situation that persists to today. Local and national authorities continue to deny the camp detainees the right to freedom of movement. Many are underfed and denied access to a livelihood, health care or other services, creating conditions of life designed to be destructive—another act of genocide.

Importantly, the 2012 violence took place, for the most part, in Buddhist-majority townships outside of northern Rakhine State, where the more recent attacks took place.

In 2015, many Rohingya put their collective fear of continued mass atrocities on hold in exchange for a much-needed dose of hope. The long-time opposition party, the National League for Democracy, won a landslide victory in national elections, ushering human rights icon and Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi to power. Through the constitution, though, the military barred Suu Kyi from becoming President, but a clever workaround provided her with a new position, State Counsellor, through which she became the de facto head of State.

While Myanmar citizens lined up to vote in 2015, my colleagues and I were with Rohingya communities as they lined up for meagre food rations in the internment camps in Rakhine State. The government of former President Thein Sein denied the Rohingya the right to vote in the elections. But most of the Rohingya we met on election day remained exuberant about Suu Kyi’s victory. Many had long supported her and assumed she would, in turn, support them. They believed a new day was dawning.

They were wrong. We were all wrong.

Suu Kyi’s administration has not only failed to prioritize human rights, but State Counsellor Suu Kyi has also become an authoritarian human rights violator. In a historic fall from grace, she has effectively overseen the Rohingya genocide.

Suu Kyi and her offices deny any wrongdoing by the Myanmar authorities in Rakhine State and have wilfully failed to prevent or remedy the military’s crimes. The Suu Kyi government has stoked anti- Rohingya sentiment with appalling propaganda, imprisoned journalists, denied UN investigators access to the country and failed to use their power in Parliament to repeal laws that contravene Myanmar’s human rights obligations.

What does this mean for the Rohingya?

Genocides are often considered primarily in the context of

the perpetrators and the dead. But genocide is also about the survivors—the living.

The survivors in these pages bore witness to the horror and escaped, and they are a testament to the enduring will to live and to the resilience of life.

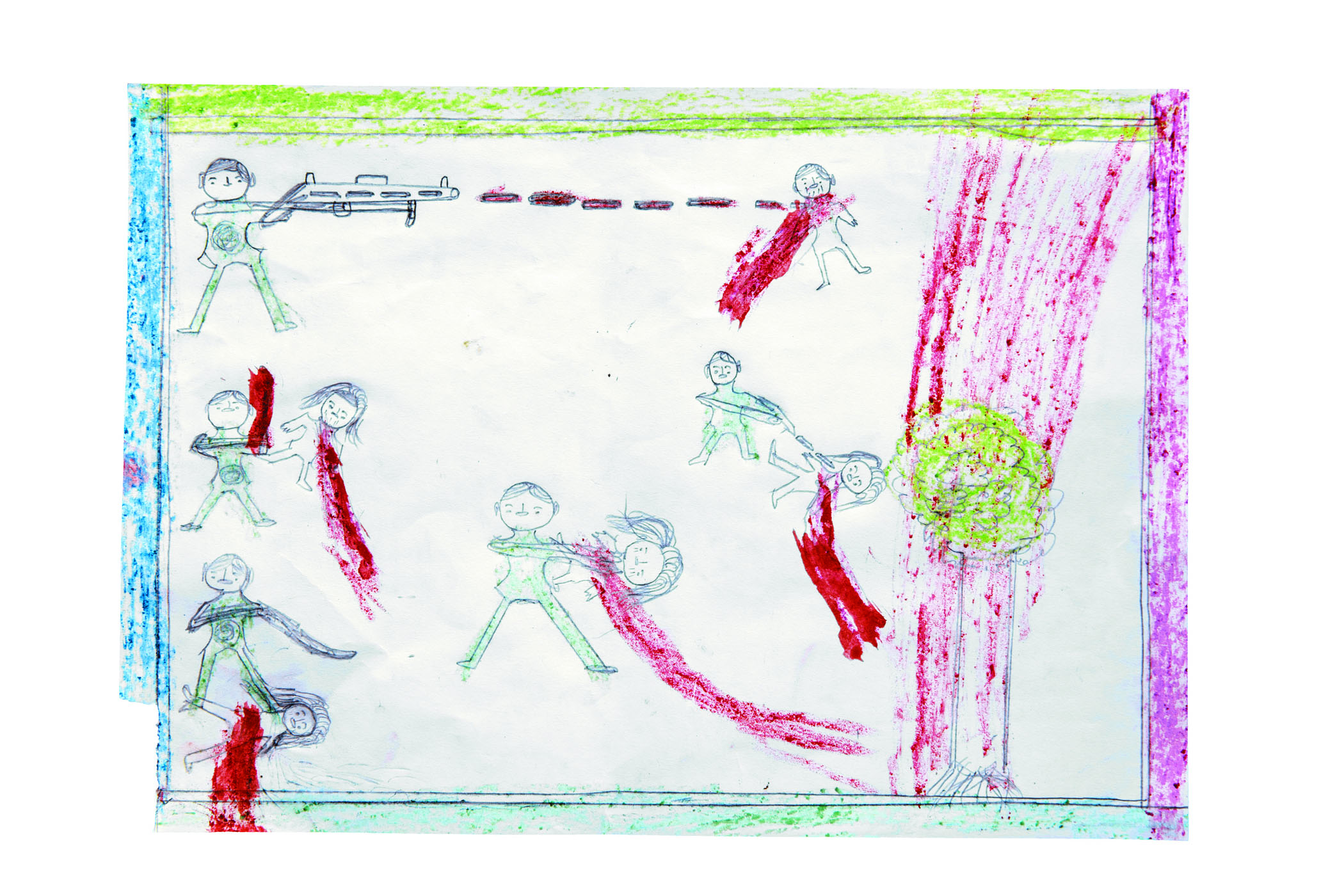

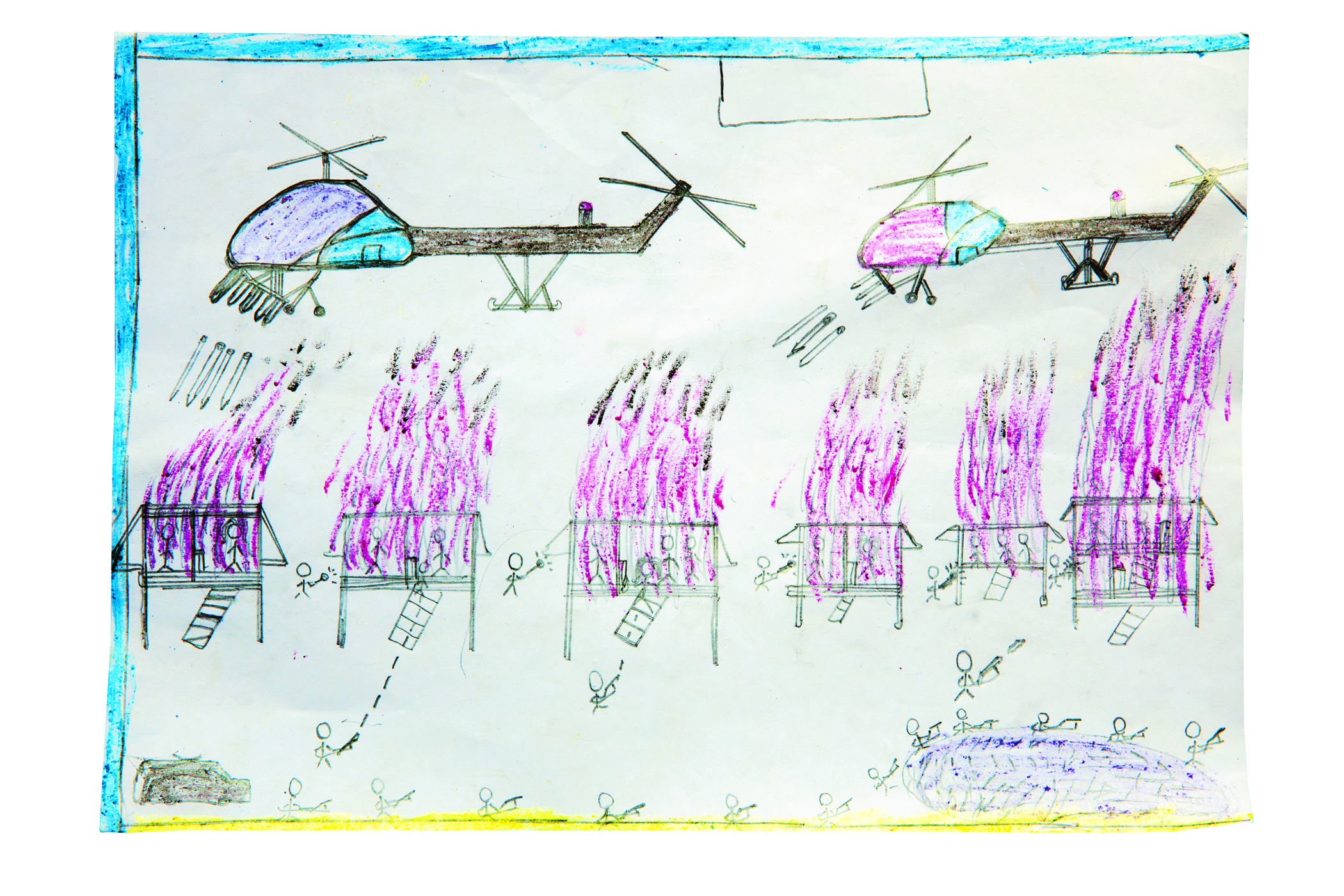

Children's Drawings

The drawings on the following pages shock with their simple representation of horrors witnessed by the child survivors of the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya population of Myanmar. Their style may be all too familiar from our own childhoods: stick-figure kids and square houses with triangle roofs, a round orange sun, windy paths. But these are not the drawings of a childhood of peaceful bliss—they document crimes against humanity.

Helicopters in the sky rain bombs and bullets onto villages, setting them afire as their populations take flight. Armed uniformed soldiers with automatic weapons murder children, their blood spilling everywhere. In one complex drawing, with green mountains in the background, soldiers stream out of an army camp to attack and burn down a Rohingya village, while other Rakhine villagers join the attack on their neighbours. Red is often a dominant colour, representing rivers of blood and the fire consuming their homes.

These are not imaginary scenes. In interview after interview I conducted with adult survivors of these attacks, they described having their Rohingya villages attacked by army troops, often supported by military helicopters, the massacres that ensued and the burning of their homes as they fled. Many survivors described in the most painful detail how their relatives were killed in front of them—at times, children were beaten to death and thrown on fires, sometimes even alive. Women were raped, often before being beaten unconscious and left crumpled in a house that was then set on fire, leaving the survivors, the ones who regained consciousness and managed to escape, with extensive burns.

Even after two decades as a human rights investigator, the sheer barbarity of the atrocities committed against the Rohingya villagers shocked me to the core. My notebooks are stained with my own tears, as I often found it impossible not to cry along as survivor after survivor recounted the horrors they had witnessed.

Of course, we need to be careful when interpreting children’s drawings. They are, after all, still children who might be easily influenced by the drawings and accounts of other children and the counsellors helping them work through their trauma. Their drawings may not always represent what happened in their village but, rather, they may be a collective memory of what they and their peers experienced, blending their experience with those of others. The drawings may represent more the collective memory of a community. But that doesn’t detract from their relevance or importance.

For those of us who documented these atrocities and witnessed first-hand the haunting impact on thousands of Rohingya children, we will forever be affected by the severity of their trauma. Many have simply gone mute, staring into the distance and incapable of communicating their hurt. They are children who witnessed their parents and siblings murdered with utmost brutality—their childhood innocence ripped from them.

In the Rohingya crisis and in these children’s drawings, we confront the depths of human depravity towards fellow human beings. What these children have witnessed will leave them forever haunted. But it should haunt us all.

Peter N. Bouckaert, 2018

Nur Mohamed, the uncle of missing 13 year-old girl Rupchanda Begum, points her out in family photo. A young girl in a turquoise skirt stares out from a faded colour photograph. Holding a small child in her arms, she stands among a group of adults and children posing in what appears to be a family portrait. According to Nur Mohamed, a Rohingya refugee living in Hakimpara camp, the girl pictured in the front row is his niece, Rupchanda Begum, then 10 years old.

‘She was a pretty girl, and intelligent too,’ says Mohamed. ‘She never got in trouble.’

Listening to the conversation are Rupchanda’s two younger brothers, Yasin, 9 and Ali, 7. The two boys were the last to see Rupchanda before she vanished one day last September. The three siblings were living with an aunt in Kutupalong camp at the time.

They had come to Bangladesh only weeks earlier as orphans, after their parents and four brothers and sisters were killed during the wave of violence that swept their home state of Rakhine. That morning, the three children had gone to join refugees waiting in line for snacks distributed by an NGO.

‘It was very crowded. People were pushing each other,’ recalled Yasin. Suddenly, their sister was nowhere to be seen. ‘We were crying – we had no idea where she had gone.’ Public announcements were put out on loudspeakers, but to no avail. Rapuchandra had disappeared. ‘I think someone took her,’ says Mohamed’s wife, Rahiema. The couple now look after Yasin and Ali in addition to their own six children. ‘It is difficult to

look after so many,’ he says. ‘But what else can we do?’

Simon Ingram, 2018

Almas Kahtun

Almas Khatun, 40, survived the Tula Toli massacre. Her six children, husband and father were among 22 family members who did not.

‘The military used to come to our village and take anything they wanted. Silver, gold, tools, utensils, chili, rice or furniture. They chased us and beat us. They tore down all our mosques and did not allow us to pray. If we cultivated food, the Rakhine would come and snatch our crops as well. So we had to work very hard to survive.

On the morning of 27 August, we woke up to pray, and I cooked chicken for my children. I could not feed them. The soldiers came, and we had to start running. They were shooting and burning houses, and when we ran down to the river bank they surrounded us on all sides. Then they started slaughtering people. They did not say anything and did not spare anyone. My husband, Noor Kabir, was stabbed, like we cut a watermelon. I watched with my children as he was killed.

They killed my children by throwing them on the ground and hacking them into pieces, one by one, then they threw them into the water. My youngest was just 3 months old. He was resting on my lap, he cried out. How could they kill them all?

When they were done, they dug pits and splashed petrol on the rest of the bodies to burn them, making sure nothing remained. After that, some soldiers went around the village torching homes. They even killed our animals with gunshots.

Once all of the men were killed, groups of soldiers started taking Rohingya women into houses. As soon as I was inside, I was beaten and knocked out. They started hacking us with blades; some died immediately and some passed out. When I woke up, I was lying on bodies covered in blood. I did not move; it was like I was dead. There was another woman beside me, a relative. She called out for her husband, ‘Tuharni, Tuharni, Tuharni.’ Soldiers who had moved on to another house heard her and came back. They slashed her face and killed her.

Then they started setting the roof on fire. It spread fast, and we felt the heat coming towards us. I grabbed a piece of wood and stood up. I had deep cuts on my neck and hand, and it was broken. I went with another woman towards the bath house. On our way I picked up a child who was cut on its side, its intestines spilling out. I thought it was my child.

I went and hid under a mango tree with the dying child. But then I saw two soldiers coming back. They saw me and the bleeding baby in my arms, and I think they felt a little mercy, for they did not shoot us or cut us again. Slowly, I went to another house near my brother-in-law’s house and left the child on a chair.

Beyond the paddy fields in our village there are hills. With the help of a local boy and a crutch, I walked all night. My body was so full of pain. Insects and leeches were biting us, and it was raining as well. But we had to keep moving to escape the soldiers. Along the way, we met some other women with bad burns. We kept going until we reached the lowlands and spent another night there. I told the others that if the military comes back, we will not be able to escape. So we walked and walked for two more days and nights, until we reached Balukhali village.

A family started crying as soon as they saw us. They gave us clean clothes, some medicine, rice with chicken and a mat to sleep on. We stayed there for one night. In the morning, they carried four of us on stretchers to the seashore. The boatman cried, too, and I think he called the (Bangladeshi) border guard to explain our situation so we could cross over. He gave each of us 100 taka.

There were crowds of people on the shore when we arrived. Everyone gathered around us. They gave us snacks and juices and arranged a driver to take us to the hospital in the Kutupalong camp. I had to stay there for more than one month. Somehow, Allah stopped my bleeding.

When I was released, there was no one to help me, or hold me. I was dropped off in the market next to a jackfruit tree. I searched and searched, then I met a man from my village, and I started screaming. They found my nephew and that’s how I met my sister here. Now, if I need to do anything, I have to get others to do it. My hand is not healed, so my nephew goes to collect my rations.

My husband earned and took care of us in Myanmar. He was a very good man. He was fair, understanding and loving. That’s why I’m worried now. I don’t know that I’ll ever find another man like him. Several here have asked to marry me—today, one man was supposed to come. But I’ve rejected them all. Who will really take care of me?

My son was also a hard worker. He used to work in the paddy fields and help us. When my eldest daughter came home from school, she would work with him. This year she would be an adult, and next year I could find a bride for my son.

I keep thinking about my children, how I couldn’t save them. If just one of them had survived, I could convince my heart to go on. My house was so full of life, but they came and took that away.’

14 December 2017

Hasina Begum

Hasina Begum, 21, was held at gunpoint with other women in Tula Toli while soldiers executed men and boys, splashed their bodies with gasoline and heaped them into a bonfire. Clutching her baby Sohaifa, she and many other women were forced to watch while soldiers burned the bodies of those they had killed. ‘I was trying to hide my baby under my scarf, but they saw her leg,’ she says. ‘They grabbed my baby by the leg and threw her onto the fire.’ They then forced Hasina and her sister-in- law, Asma Begum, into a hut, where they were stripped, raped, beaten to unconsciousness and left to die.

When Hasina regained conscious- ness, the hut was on fire. Her sister-in- law was alive, too. As fire raged around them, Hasina and her sister-in-law punched a hole through the wall and ran away naked. The pair soothed their burns in the mud and were given clothes by a Rohingya family. It took them three days to reach the safety of Bangladesh. Hasina is tormented by nightmares of the child she lost.

3 December 2017

Hasina Begum and Asma Begum

Hasina Begum, 21, (right) and her sister-in-law, Asma Begum, was held at gunpoint with other women in Tula Toli while soldiers executed men and boys, splashed their bodies with gasoline and heaped them into a bonfire.

3 December 2017

Minwara Begum

Minwara Begum, 17, lost six family members in the attack on Tula Toli.

She was cooking breakfast when the shooting started and was hit in the thigh with a bullet. The soldiers who found her hiding in the bush blindfolded her, bound her hands

and legs with cloth and gang-raped her. She regained consciousness and burned off the cloth in order to crawl away. She spent the next five days walking through the jungle with a group of survivors to reach Bangladesh, where she was hospitalised.

‘I feel so restless and worried. People say they’re going to send us back to Myanmar,’ she says. ‘They did these things to us—they raped us—I’m not afraid to talk about it. I don’t feel ashamed to tell the world. I want justice, but I know the world cannot give me justice. If there’s anyone who could give us justice, it would have happened a long time ago.’

22 November 2017

Foruda Khatun

Foruda Khatun, 50, survived the massacre at Tula Toli village in Myanmar and arrived in Bangladesh with her sons and a neighbour. Her husband was killed during the attack on their village by Myanmar soldiers.

22 November 2017

Rashida Begum

Rashida Begum, 25, and her husband survived the massacre at their Tula Toli village. Their first child, born 28 days before the attack and not yet named, did not. Rashida and five women were dragged into a house by uniformed men. A soldier pulled the baby from Rashida’s arms and killed him in front of her. The men tore off her clothes, and one man sliced her neck with his knife as she fought back. She was beaten and raped alongside the four other women. As the men left the hut, they set it ablaze and left the women for dead. Rashida woke with her skin burning. She kicked her way out of the haze and hid, naked, in a nearby field, but she wishes she had not survived.

‘It would be good if I, too, died because if I died, then I wouldn’t have to remember all these things. My parents were killed, too, lots of people were killed,’ Rashida told

a CNN journalist. ‘I constantly think about what happened. I can’t get

it out of my mind.’

20 November 2017

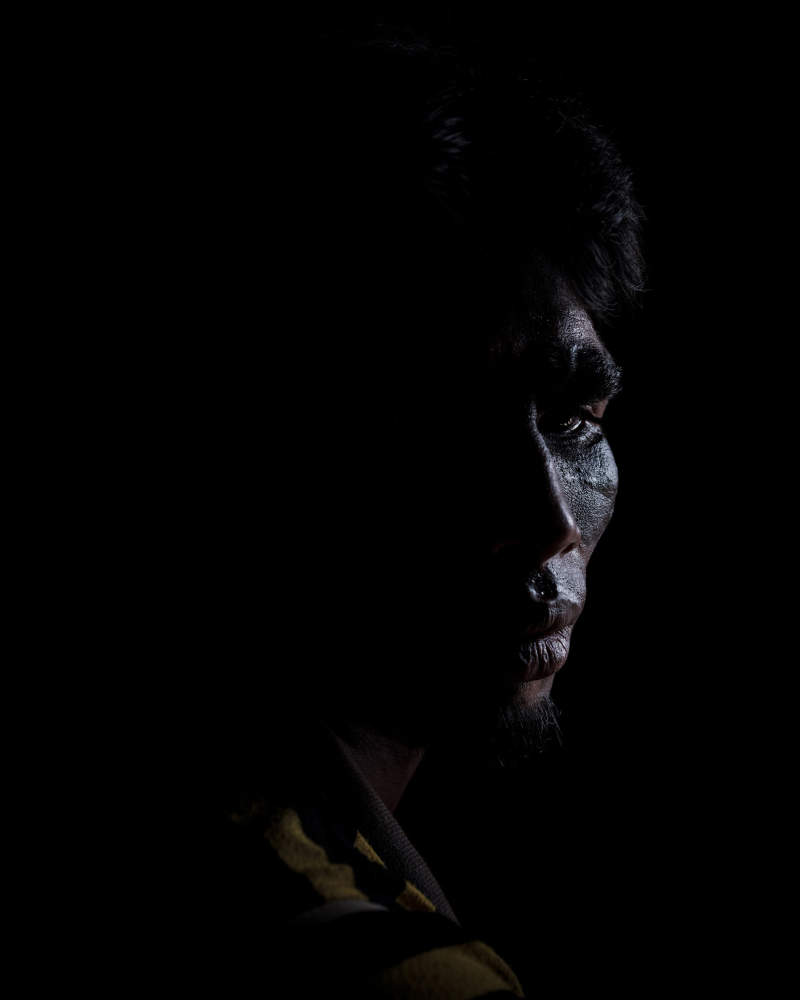

Nazmul Islam

After the [October] 2016 attacks, we heard that many people were slaughtered and raped. Police came and tore down our fences and looted our homes. We were not allowed to keep our tools. Aid rations were cut off for more than six months, and many of us didn’t have food in the village. We were also afraid something bad was going to happen to us.

On the afternoon of 27 August [2017], I was called to the Rakhine side of the village. I’m an influential person, and the chairman said he had something urgent he needed to discuss. As soon as I arrived, border police arrested me and took me to the small guardhouse next to the chairman’s office. I was told to stay put or I would be killed.

At around eight in the morning on 30 August, I heard lots of gunfire, bombs exploding. Soldiers attacked with guns and launchers and militia were chopping with swords and awls. Children were thrown in the fire. Some were lifted by their feet, smashed into the wall of a house and thrown into the flames. Everything was ablaze. I could smell burning flesh.

Then an army helicopter came with weapons and fuel. Administrators were called and told they needed 20 volunteers to dig graves and burn the bodies. A border police officer ordered his men to stay away from the riverbank. The soldiers were not from Rakhine; they were from Division 99. They said, ‘We are allowed to shoot and kill everyone.’

By noon, two-thirds of Tula Toli was burnt to the ground. The soldiers were bragging in front of me how they burned people alive, stole jewellery and raped women in groups. They had official orders to do this. I know, because I was in the army for many years. Nothing happens without the approval of commanders.

It started raining hard and lasted all night. The next morning, water was coming down from the mountains and dead bodies were floating in the river. I could see them there for ten days. When the rain stopped, the soldiers torched the rest of the village. They finished everything: people, buildings, dogs. Did they need to burn all the houses and kill everyone if they are not committing genocide?

Later they asked me if I was the man who left the army and converted to Islam. They told me that if I came back to Buddhism, they would take care of me. I was held for more than a month. The soldiers got drunk and danced and shot their guns. Whenever they walked by, they beat me and kicked me.

Finally, on 1 October, they had a meeting to decide my fate: Renounce Islam or they would kill me. I was thinking, I’m still alive without any hope. It’s like I’m already dead. I don’t know what happened to my family. What should I do?

On 3 October, they were busy preparing a meal for a festival the next day. I escaped by jumping into the river. They shouted after me and shot five times but missed. I ran and ran. In one village, I got a ride on a motorbike and made it to Maungdaw, where I borrowed money for the boat crossing. Then I came here and arrived by the grace of Allah. Allah is great.

Now I’m very sick. I don’t know whether I’m going die today or tomorrow. I’m not afraid of dying. But I worry about my children and other young Rohingya, they have lost their way. The world is talking a lot about Rohingya, but they should come and help us—not only with words but with support. We don’t have any light in our life. Everything is dark.

14 December 2017

Islam passed away at an MSF clinic on 10 August 2018.

Syedul Amin

Syedul Amin, 30, lived in Tula Toli with his wife, Mohsena, and two children. He tried to convince his father to leave with them following the 25 August attack by the Rohingya militants on police posts, but his father refused to leave—community leaders said everyone would be safe. When the shooting started, Syedul and his family hid in the paddy fields. The army fired a continuous burst of fire towards the paddy fields. ‘Had we raised our heads (during the massacre),’ he says, ‘we would have all been killed.’

From his position in the paddy fields, Syedul watched the army carry out the massacre in the village. ‘The army forced the men to dig a shallow ditch’ Syedul tells. The men were then executed and thrown down into the ditch. ‘Then the helicopters arrived above us and unloaded jerry cans of gasoline near the ditch,’ Syedul continues. The army threw the jerry cans with gasoline into the ditch. ‘There was a huge explosion of flames.’ Children and infants were also thrown in, ‘often alive,’ says Syedul.

Syedul and his family escaped to Bangladesh and now live in a refugee camp outside Cox’s Bazar.

12 December 2018

Shafiqa Begum

Shafiqa Begum, 20, had married only three months before the Myanmar military attacked her Tula Toli village. The army and local collaborators burned down dwellings and unleashed a massacre, gunning down Shafiqa’s father-in-law and younger sister as they tried to flee. Before the attack, local authorities reportedly had ordered all boats be removed from the nearby river so that villagers could not escape. Shafiqa, her husband and other villagers stood on the riverbank as soldiers advanced towards them shooting, leaving them nowhere to go. “My husband was killed first,” Shafiqa told the USC Shoah Foundation.

Three months after the attack, Shafiqa lives as a widow in Balukhali refugee camp.

22 November 2017

Rajuma Begum

The military often came to our village. They stole chickens, vegetables, tools; we didn’t even have a knife to cut vegetables. If they found a long stick, they would take it. Any protest and you were beaten, arrested or money was extorted from you.

In the days before our village was attacked, every one of us stayed awake at night. We could see the huge flames nearby. As they burned and killed, I thought that soon they would do the same to us.

On Wednesday morning, we did not have time to eat. The military came from all sides, shooting and setting houses on fire with rocket launchers. I’ve never seen so much gunfire in my whole life. At that moment, I decided I must escape to save my life, along with my child. We ran down to the riverbank. Soldiers were rushing towards us, and we were trapped by the water.

First they killed the men. One of my relatives got shot twice. He did not die until he was shot a third time. Then he was hacked up with blades in front of our rice paddies. I didn’t know where my husband was, if he was alive or dead. People said, ‘We’ve never seen a girl who cries like you.’

A military helicopter landed and flew away again. It took several hours for all the men to be killed, their bodies destroyed. Only mothers and small girls were left. Groups of soldiers started taking them into a row of homes. My mother started crying and asking for forgiveness. My brother did also, then ran away. He was shot dead in front of my eyes.

My son, Sadiq, was on my lap. The soldiers grabbed me and threw him into a fire. He screamed, but there was nothing I could do. Many other children were burned, too. I felt like

I wanted to die.

When they took us inside the house I knew it was the end. Anyone who fought back was beaten brutally. They demanded our money and gold. I thought, ‘Why should I help them— they can take what they want after killing us.’ They hit me with a gun, and I fell unconscious. Then they raped us.

I was lying there, almost dead, until we could see the sun setting. Houses were burning around me. The soldiers closed the doors from outside and stood by as people were screaming. The fire was getting closer. I was in so much pain, but I fought out the back side [of the bamboo house] and ran towards the jungle.

In the morning, I met a lady and her daughter. We walked through the hills in the dark and tried to follow the route used by other people, looking for things on the ground. That’s how we reached Balukhali [camp]. From there, we were directed to the coast. Some men gave us hot water and medicine and arranged a boat to the other side.

It was the day of Eid. After reaching here, they took us in a vehicle to the MSF hospital, where I found my brother. He called my husband—he thought I was dead. My condition was almost like dead. Now I’m doing better thanks to him. He cooks me food and gets me medicine when he can. He loves me.

Living conditions in the camp are the worst. It’s hot, and it smells terrible. In one month I got sick four times. Recently, a lady came to see me who is 50 but she looks very young. Me, I’m just 20 but I look old because of all the stress. I don’t feel like doing anything, I have no peace of mind. When I see [Bangladeshi] soldiers here, I’m terrified and stay inside. I feel like forgetting this world.

3 December 2017

On 9 September 2018, Rajuma gave birth to a baby girl named Jamela (‘Beauty’). ‘What happened in the past,’ she says, ‘cannot be recovered by crying and crying.’

Machete, Sickle, Axe, Hoe

For generations, the Rohingya have used handmade tools to farm ancestral lands. In the months leading up to August 2017, their tools were taken and destroyed. Myanmar security forces went house to house across northern Rakhine State, seizing sharp and blunt objects and stealing food. An absence of tools and the ever-present threat of violence combined to interrupt the harvest cycle that sustained Rohingya villagers. Access to local markets was practically cut off, and gatherings were forbidden. As hunger gripped the countryside, the government moved to block UN food shipments.

When the military unleashed a genocidal fury, Rohingya villagers were defenceless. The soldiers and helicopters raining hellfire were backed by non-Muslim vigilantes, trained and armed by the government. The everyday tools stolen from the Rohingya were now wielded as weapons of war. ‘They had long swords, machetes and knives,’ says an eyewitness from Maungdaw Township. ‘The army shot us, and then the Rakhine hacked us,’ adds a massacre survivor from Rathedaung. ‘Some people were beheaded,’ another recalls, ‘and many were cut.’

The refugees flocking into Bangladesh bore the marks of savage, near-death encounters: deep gashes, broken bones, missing limbs. But in the camps that sprawl as far as the eye can see, machetes, sickles, axes and hoes have helped make life possible again. Every day, trees are cleared and terraces dug into hillsides to make space for shacks of split bamboo. Down in the ravines, barefoot men and women till small vegetable plots to supplement meagre aid rations. They pick up work at local rice paddies and in the markets. And when fatigue or sickness claim another life, they gather their tools. A hole is dug, a fence is built; and the dead are delivered back to the red soil.

No Place on Earth

by Patrick Brown

The Rohingya are a predominantly Muslim minority group from Rakhine State, in western Myanmar, numbering around a million people. Legislation adopted in the early 1980s stripped them of their citizenship. They lost their jobs, and thousands were herded into controlled settlements, their freedom of movement taken away as well. After decades of persecution and deprivation, violence erupted in Rakhine State on 25 August 2017 after a faction of Rohingya militants attacked police posts, killing one soldier, one immigration officer and 10 policemen. Myanmar security forces supported by groups of Buddhists, retaliated, attacking Rohingya villages and burning homes. Within two days, I was hearing reports from friends and colleagues in Bangladesh that Rohingya Muslims were flooding across the border with horrific stories of barbarity perpetrated by the military and vigilantes.

The stories were more than frightening, and I sensed this was the start of something big and terrible. Having lived for two decades in neighbouring Thailand, not far from camps of other ethnic refugees from Myanmar, reports of targeted ethnic violence were common, including the murder of men, the rape of women and the razing of villages. These reports were somehow different.

Access to Rakhine State has always been limited by the army—the Tatmadaw—and there was no information coming out that August. But the news from Cox’s Bazar, in southern Bangladesh, across the border from Rakhine State, made clear a mass atrocity was being perpetrated.

I was there within days but little prepared for the immensity of what I saw that first night and continued to see over the following weeks and months. Children had carried younger siblings through flooded fields. People of all ages lugged sacks stuffed with what remained of their possessions. Hungry people, who had walked for days through jungle, carried nothing, they had nothing other than the clothes they wore. It wasn’t long before the hundreds of desperate people became thousands, then tens of thousands and then hundreds of thousands.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called what took place in Rakhine State ‘a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.’ That word has always struck me as odd. There is nothing clean about ethnic cleansing—it’s murder, it’s rape, it’s people being slaughtered in the most systematic and evil way.

Euphemisms and diplomatic language can obscure the crimes carried out by oppressive regimes. Photography sees through the cold, clinical terminology.

It forces a confrontation, a reckoning, by putting a face—thousands of faces in this case— to the cruelty. There were witnesses, and they live on. Through the photographs of their survival, there can be no denying what ethnic cleansing really looks like.

As I was to discover, day after day, the cruelty doesn’t end when the oppressed escape. It travels with them. There were many incredibly hard moments in my following the Rohingya, but 28 September 2017 stands out. I had a phone call, a colleague telling me a boat carrying Rohingya had capsized just off the coast of Bangladesh, not far from where I was. It was early evening, but the sky was already black due to a massive thunderstorm rolling in off the Bay of Bengal. The fury was like nothing I had experienced before, and I could only think that anyone who would take to the waters in monsoon season must be running from something truly evil.

I would later learn more than 80 people had been on the boat and only 17 had survived. Many of the dead were women and children. When I arrived at the beach, cars blocked the road. I found a small mob of police, local and international journalists and fisherman who had helped carry 15 bodies up to the coastal road.

Amid the chaos, I looked at the bodies lit by car headlights and noticed how the rain had gently moulded the sarong fabric covering them along their individual features. There were small ears, delicate noses, tiny arms. The resulting photograph captures a stillness, but ultimately, for me, it is the image of ethnic cleansing.

It’s not that the photograph itself is horrific—it’s what it represents. These children have names, a mother, a father, brothers and sisters, grandparents. They fled their home in fear, braving the Bay of Bengal in the middle of a monsoon storm. The day after this picture was taken, I photographed survivors burying them in a mass grave. They’re just a small part of a much bigger story.

I’ve returned to the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar many times. It’s a city the size of Copenhagen and now more densely populated than Manhattan. Trapped on the edge of a foreign country and rejected by their ancestral homeland, the Rohingya have nothing there but their will to survive on whatever support we provide them. They are dependent for all basic necessities: clean drinking water, schooling, health care, jobs. Most of all, a safe and dignified place to call home.

No Place On Earth is the recipient of the 2019 FotoEvidence Book Award with World Press Photo.

The images in this book were made on various assignments for the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

No Place On Earth by Patrick Brown contains 98 colour photographs with the main essay by journalist Jason Motlagh, an introduction text by Matthew Smith, director of Fortify Rights. The book is designed by the renowned book designer Stuart Smith with photo editing by Gemma Gerhard and Claudia Paladini.

The Book Award is given each year to a photographer whose work demonstrates courage and commitment in documenting social injustice.

No Place On Earth was made possible with the support of the Grodzins Fund, World Press Photo, the Pulitzer Center, Fortify Rights and Fujifilm.

The book is available for purchase from FotoEvidence.