For Brazilian governments, irrespective of their political leaning, the Amazon is an ‘empty space’ whose development is essential for the country’s economic growth.

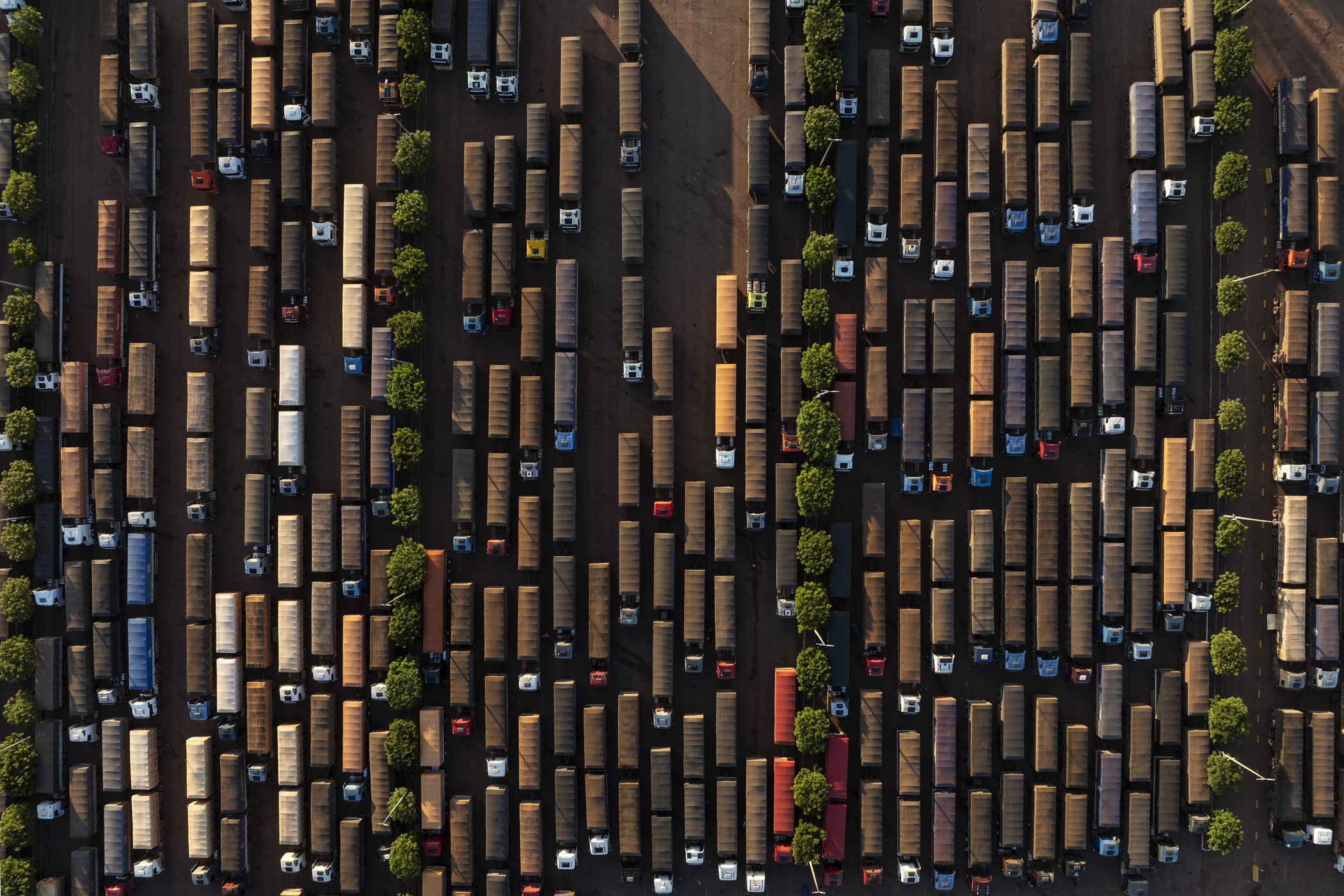

Itaituba, Brazil. May 3, 2025. Trucks loaded with soybeans are parked at a gas station at the junction of BR-163 and Transamazônica highways, near Miritituba, Pará. Miritituba will be the final stop of Ferrogrão, a railway that will be used to transport grains from Mato Grosso, the country's main soybean-producing region, to the Tapajós River.

But in spite of current President Lula’s election promises to reverse this trend and defend the Amazon the region is now threatened by colossal new infrastructure projects. This summer, under his leadership, the Brazilian congress voted through the now infamous ‘Devastation Bill’ following significant pressure from the powerful agribusiness, oil and gas lobbies. The bill relaxes and reduces environmental controls on development in the region encouraging further deforestation and the construction of large scale projects. What nearly all these projects have in common is their top down lack of concern for the needs of local populations.

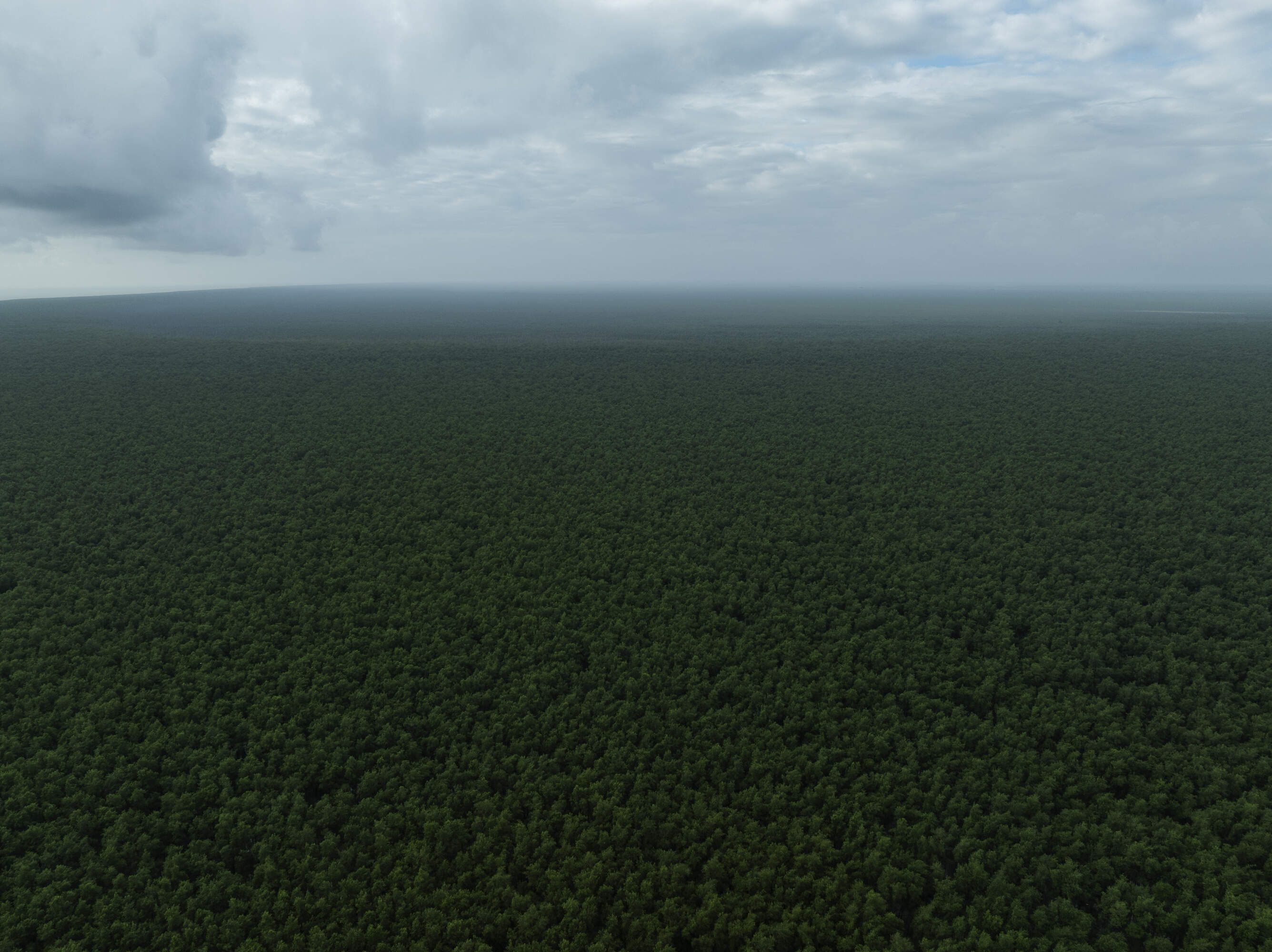

There are three major initiatives under way which have the potential to wreak environmental devastation: paving the 400km middle section of the BR-319 highway connecting Manaus to Porto Velho; constructing a 933 km railway from the Mato Grosso to Itaiuba popularly known as the Ferrogrão (Grain Railway); opening up the northern Amazon basin to oil exploration.

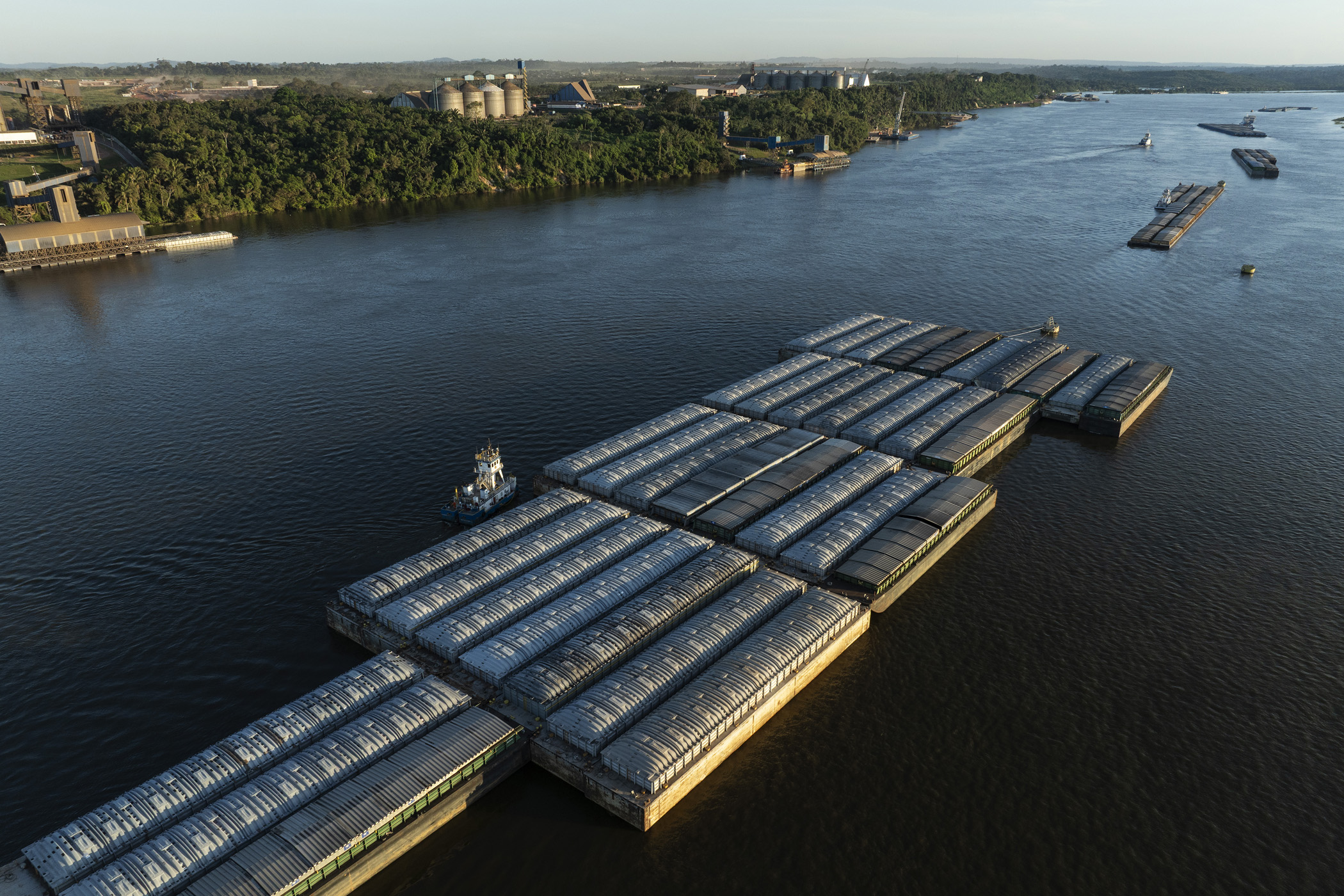

The Devastation Bill allows the government to classify projects as “strategic,” streamlining them through a one-phase, one-year review. The Ferrogrão railway will create an export corridor connecting Brazil’s largest soybean producing area to the port of Miritituba. Brazil is the number one producer of soybeans in the world boosted even further by Trump’s tariffs which have meant China now no longer sources soybeans from America and has switched to Brazil for its supply. Huge tracts of land reclaimed from the rainforest are given over to soybean production. The railway will follow the route of the BR -163 a highway that is no longer able to accommodate the expansion of the soybean industry.

“February and March on BR-163 is hell,” says Ilson José Redivo, president of the Sinop Rural Union. “Trucks line up endlessly.” Two to three thousand lorries a day travel on the BR 163 during harvest season. Even though the project has not yet left the drawing board the mere prospect of its construction is already driving deforestation to open up new areas for soybean cultivation. Indigenous lands, riverside communities and conservation areas along the route of the railway will be all be directly affected while none of the people in these areas have been consulted.

Novo Progresso, Brazil. May 01, 2025. Kayapó women from the Mopkrore village collect water from the Curuaés River, in the Menkragnoti Indigenous Territory in Novo Progresso, Pará. With the prospect of the Ferrogrão construction project, the Indigenous people are already feeling the pressure on their surrounding territory, driven by increased deforestation and the expansion of soybean plantations. For this community, which depends on river water for its survival, contamination from pesticides used in soybean cultivation could have dramatic consequences.

Humaitá, Brazil. Tree rows are burned in a deforested area near the junction of the BR-319 and Trans-Amazonian highways, close to Humaitá, in southern Amazonas. The opening up of new areas for soybean cultivation has been one of the drivers of deforestation in this region.

Humaitá, Brazil. September 11, 2025. Workers pave the BR-319 highway between the city of Careiro and the community of Igapó Açú, in Amazonas. The highway, which connects the cities of Manaus and Porto Velho, crosses one of the most preserved areas of the Amazon, and its paving could have tragic effects on the forest and traditional communities.

The prospect of paving the 400km middle stretch of the BR-319 highway could also trigger further occupation, land grabbing and deforestation in a largely preserved area of the Amazon. The original highway built in the1970s tore through a huge block of untouched rainforest but in the 1990s, lack of maintenance and extreme weather meant much of the road lost its paving and the land connection between the two major Amazonian capitals of Manaus and Porto Velho was abandoned. Repaving the road would reverse this process. Even before the arrival of asphalt, in the final years of Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, illegal secondary roads reaching into the forests accompanied by an explosion of deforestation were multiplying. All of which threatens traditional communities whose voices remain unheard and whose opinions are never sought even by the legal planners and developers.

Rorainópolis, Brazil. June 13, 2025. Cable launching area at the Manaus - Boa Vista power line construction site, within the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, in Roraima. During the construction of the power line a decisive change has occurred in the way a project of this size is executed in the Amazon within a recently contacted Indigenous territory: the Kinja ( as they call themselves ) have taken a leading role in overseeing the works. This model has not been seen in other large projects in the Amazon.

Oiapoque, Brazil. July 23, 2024. Mangrove in Cabo Orange National Park, Amapá. The region at the northern tip of the Brazilian coast, where Cabo Orange National Park is located, is home to one of the best-preserved mangrove forests on the planet. The oil exploration project in this region of the Brazilian coast puts traditional communities and the environment at risk. ( Photo: Lalo de Almeida )

Itaituba, Brazil. May 04, 2025. Barges used to transport grain on the Tapajós River are anchored in front of Miritituba, near the city of Itaituba in Pará, Brazil. Miritituba will be the final stop of the Ferrogrão railroad, which will be used to transport grain from Mato Grosso, the country's main soybean-producing region, to the Tapajós River.

Novo Progresso, Brazil. Kayapó women from the village of Baú travel along a stretch of the Baú River by boat to access the cumaru seeds collecting area in the Baú Indigenous Territory, in southern Pará. The Baú Indigenous Land is the Kayapó territory closest to the Ferrogrão railway planned route, about 30 kilometres away. The Indigenous people are already feeling the impacts of the project on their surrounding territory, such as deforestation and an increase in soybean cultivation.

Oiapoque, Brazil. Children play in a canoe in front of the village of Santa Isabel in the Uaçá Indigenous Territory, in Oiapoque, Amapá. Around 12,000 indigenous people live in three territories in the Oiapoque region. The oil exploration project in this area of the Brazilian coast puts traditional communities and the environment at risk.

Now on the eve of Brazil hosting the COP30 talks in Belem in November President Lula has come under fire after the state oil company Petrobas was granted permission to begin drilling in the Foz de Amazonas region after a five year battle. The concession is off shore at the northern tip of the Brazilian coast where the Cabo Orange National Park is located, home to one of the best preserved mangrove forests on the planet. Any oil spill and contact with the coast would be disastrous causing irreversible damage to life in the area. Once again even before prospecting has taken place waves of migrants are arriving and settling in squatter settlements on the outskirts of Oiapoque on the edge of the park. While the drilling is yet to commence in the Foz de Amazonas gas exploration is already a reality in the centre of the Amazon. In Silves near Manaus a gigantic natural gas venture is booming. As with other major infrastructure projects in the region the expansion of gas and oil extraction in the forest ignores the existence of the existing communities.

Silves, Brazil. June 23, 2024. Opening of a natural gas well near Eneva's Azulão Gas Treatment Unit, located in the municipality of Silves, Amazonas. The expansion of gas through the forest is in full swing, with new wells being drilled for prospecting, pipelines being laid in different parts of the jungle, the gas pipeline taking shape in different sections of the forest, roads being opened for the movement of workers, and the consolidation of the project.

Silves, Brazil. June 25, 2024. Natural gas extraction well next to Eneva's Azulão Gas Treatment Unit, located in the municipality of Silves, in the state of Amazonas. The company, which owns the largest private oil and gas exploration project in the Amazon, has obtained licences to drill 29 gas wells in blocks in the region between the municipalities of Itacoatiara, Silves and Itapiranga, in eastern Amazonas.

Silves, Brazil. June 23, 2024. Gas pipeline under construction near Eneva's Azulao Gas Treatment Unit located in the municipality of Silves, Amazonas. The expansion of gas through the forest is in full swing, with new wells being drilled for prospecting, pipelines being laid in different parts of the jungle, the gas pipeline taking shape in different sections of the forest, roads being opened for the movement of workers, and the consolidation of the project.

Silves, Brazil. June 27, 2024. Workers involved in the construction of the Azulão field, the main natural gas exploration project in the Amazon, board a ferry to cross from the city of Silves (located on an island) to their workplace. The expansion of gas through the forest is in full swing, with new wells being drilled for prospecting, pipelines being laid in different parts of the jungle, the gas pipeline taking shape in different sections of the forest, roads being opened for the movement of workers, and the consolidation of the project.

Itaituba, Brazil. May 03, 2025. Entrance to a gas station on the Trans-Amazonian Highway, near Miritituba, Pará. Miritituba will be the final stop of the Ferrogrão railroad, which will be used to transport grain from the Mato Grosso region to the Tapajós River.

Humaitá, Brazil. September 13, 2025. Burnt Brazil nut tree in a deforested area on the banks of an illegal branch road leading off the BR-319 highway in the district of Realidade, in Humaitá, southern Amazonas. The prospect of the BR-319 being paved has fueled illegal land sales, land grabbing and increased deforestation rates in the region.

Sinop, Brazil. April 29, 2025. Trucks carrying soybeans travel along the BR-163 highway near Sinop, Mato Grosso. Most of the soybeans produced in this region travel north along the BR-163 highway to the port of Miritituba on the Tapajós River, where the grains are loaded onto barges and transported to the Amazon River, from where they are transported by ship around the world.

Itaituba, Brazil. May 3, 2025. Trucks loaded with soybeans are parked at a gas station at the junction of BR-163 and Transamazônica highways, near Miritituba, Pará. Miritituba will be the final stop of Ferrogrão, a railway that will be used to transport grains from Mato Grosso, the country's main soybean-producing region, to the Tapajós River.

Humaitá, Brazil. September 13, 2025. A truck travels along the unpaved section of the BR-319 highway between the community of Igapó Açú and the district of Realidade, in southern Amazonas. The highway, which connects the cities of Manaus and Porto Velho, crosses one of the most preserved areas of the Amazon, and its paving could have tragic effects on the forest and traditional communities.

Novo Progresso, Brazil. April 30, 2025. A line of trucks carrying soybeans travels along BR-163 near the Mato Grosso -Pará state border. During harvest season, between 2,000 and 3,000 trucks carrying soybeans travel daily along BR-163 highway between the producing regions in Mato Grosso and the port of Miritituba on the Tapajós River.

Manicoré, Brazil. The number plate of a truck stuck in the mud on the unpaved section of the BR-319 highway between the community of Igapó Açú and the district of Realidade in the south of the state of Amazonas. During the Amazonian winter, the rainy season, the road becomes impassable, making land connections between Manaus and the rest of the country impossible. The highway, which connects the cities of Manaus and Porto Velho, crosses one of the most preserved areas of the Amazon, and its paving could have tragic effects on the forest and traditional communities.

Itaituba, Brazil. May 02, 2025. Workers Carlos Henrique Ramos Silva (white shirt), Daniel Oliveira Ribeiro (shirt on face), Delson Andrew (red cap) collect soybeans from a truck that had an accident on BR-163 highway in the section that crosses the Jamanxim National Park, in Pará The three men make a living recovering cargo from trucks that crash along the BR-163 highway, especially during the soybean harvest period when between 2,000 and 3,000 trucks travel daily along BR-163 between the producing regions in Mato Grosso and the port of Miritituba on the Tapajós River.

Humaitá, Brazil. September 15, 2025. Gold miners observe destroyed mining rafts on the banks of Humaitá, in southern Amazonas, during a Federal Police operation to combat illegal gold mining on the Madeira River. The city of Humaitá is located at the intersection of two important Amazonian roads, BR-319 and Trans-Amazonian highway.

Humaitá, Brasil. September 12, 2025. Sign advertising the sale of land along the BR-319 highway near the district of Realidade, in Humaitá, southern Amazonas. The prospect of the BR-319 being paved has fueled illegal land sales, land grabbing, and increased deforestation rates.

Humaitá, Brasil. September 12, 2025. An illegal branch road leads to a recently deforested area along the BR-319 highway, near the district of Realidade, in southern Amazonas. The prospect of the BR-319 being paved has fueled illegal land sales, land grabbing, and increased deforestation rates.

Oiapoque, Brazil. July 25, 2024. Aerial view of the Nova Conquista informal settlement, located on the outskirts of Oiapoque, in Amapá, formed by migrants who recently arrived from the states of Pará and Maranhão. Supported by Lula and politicians of different stripes, oil on the Amazon coast is already causing waves of migration even before any prospecting has taken place. In Oiapoque, migrants from various regions of Brazil, especially Pará and Maranhão, are settling precariously in squatter settlements on the outskirts of the city.

Careiro da Várzea, Brazil. June 29, 2024. ATEM petrol station in the city of Autazes, a company that acquired part of the blocks for oil and gas exploration in the region. In 2023, five blocks for oil and gas exploration in the Brazilian Amazon were offered by the National Petroleum Agency (ANP). On the path to what could be a new oil and gas frontier in the Amazon, if the companies that won the blocks go ahead with their exploration projects, there are conservation units and six indigenous lands.

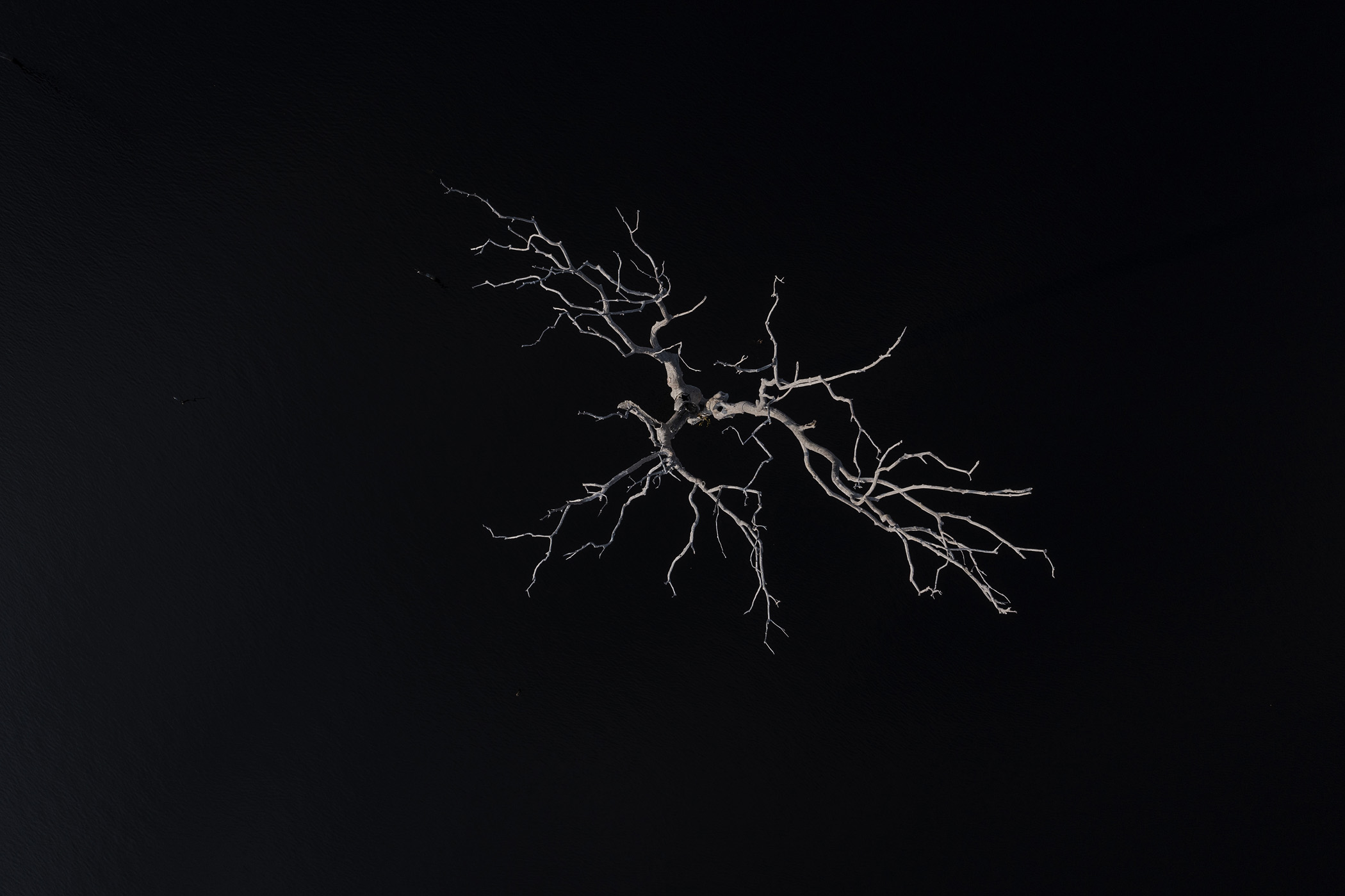

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. September 02, 2022. A dead tree in the area flooded by the Balbina hydroelectric dam inside the Waimiri-Atroari Indigenous Land. During the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964 to 1985), large-scale projects were carried out within the territory without any consultation with the Indigenous people, causing a drastic reduction in the Waimiri-Atroari population. A road tore through the territory, a hydroelectric dam flooded part of the forest, and a mining company polluted the rivers that flow through the villages. Only during the construction of the BR-174 highway in the 1970s, which cuts through their traditional territory to connect Manaus to Boa Vista, did the Kinja (as they call themselves) population decrease from 1,500 to 374 Indigenous people.

But there is a recent and unique example of the implementation of a major infrastructure project on indigenous land which demonstrates that there is a model that can take into account the concerns of local populations.

“The Waimiri Atroari people have never been at Peace. We have never been given the opportunity to think about things clearly.” in just a few sentences Ewepe Marcel Atoari, 52, sums up a common feeling of unease and alludes to the history of uninterrupted pressure on the territory of the Kinjas – the name the Waimiri Atroari use to call themselves. During the military dictatorship large projects were carried out within the territory without any consultation, causing a drastic reduction in the Waimiri-Atroari population. A roa d cut through the territory, a hydroelectric dam flooded part of the forest, and a mining company polluted the rivers that flow through the villages. Deaths occurred as a result of the Army’s offensive and diseases that had previously been absent from the territory, including measles, chickenpox and malaria.

Now a new project in the Kinja forest area has taken shape which is similar in scale to other major Amazon infrastructure intiatives – the construction of the power line between Manaus and Boa Vista - but with one major difference: the Kinjas have taken on a leading role in supervising the works, monitoring the movements of outsiders and, where possible, altering the route of the towers to reduce their impact on the forest.This is the first time, after a succession of large-scale projects in the Waimiri Atroari territory, that the Kinjas have participated in every stage of the physical works, in an attempt to reduce the damage.

Sadly this model has so far not been adopted in other large projects.

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. June 12, 2025. Workers assemble a tower for the Manaus - Boa Vista power line within the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, in the state of Amazonas. During the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964 to 1985), large-scale projects were carried out within the territory without any consultation with the Indigenous people, causing a drastic reduction in the Waimiri-Atroari population. A road tore through the territory, a hydroelectric dam flooded part of the forest, and a mining company polluted the rivers that flow through the villages. Only during the construction of the BR-174 highway in the 1970s, which cuts through their traditional territory to connect Manaus to Boa Vista, did the Kinja (as they call themselves) population decrease from 1,500 to 374 Indigenous people. Now, during the construction of the power line, a decisive change has occurred in the way a project of this size is executed within a recently contacted Indigenous territory: the Kinja have taken a leading role in overseeing the works. This model has not been seen in other large projects in the Amazon.

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. June 12, 2025. Construction drawings for towers on the Manaus-Boa Vista power line, being used on a construction site within the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory in Amazonas.

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. June 12, 2025. Workers assemble a tower for the Manaus-Boa Vista power line within the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory in Amazonas. As with all major projects in the Amazon, most of the workers who built the power line come from the poorest states in Notheastern Brazil, such as Maranhão and Piauí.

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. June 12, 2025. Workers assemble a tower for the Manaus - Boa Vista power line within the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, in the state of Amazonas.

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. June 13, 2025. Workers on the Manaus-Boa Vista power line attend an integration lecture at the Kinja Environmental Management Centre (PGAK) in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, in Amazonas. The purpose of this training is to instruct workers on the rules for working within indigenous land.

Rorainópolis, Brazil. June 13, 2025. Sawa Aldo Waimiri, Sanapyty Geroncio Atroari and Ewepe Marcelo Atroari, leaders of the Kinja Environmental Management Programme (PGAK), watch an operator use a drone to lay a cable at the Manaus-Boa Vista power line construction site in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory in Roraima. This is the first time that this model of monitoring a large construction project in the Amazon has been carried out by recently contacted indigenous peoples.

Presidente Figueiredo, Brazil. June 12, 2025. Workers assemble a tower for the Manaus - Boa Vista power line within the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, in the state of Amazonas.

Oiapoque, Brazil. July 26, 2024. Indigenous people row in the rain nearby the village of Santa Isabel in the Uaçá Indigenous Territory, in Oiapoque, Amapá. Around 12,000 indigenous people live in three territories in the Oiapoque region. The oil exploration project in this area of the Brazilian coast puts traditional communities and the environment at risk.

Humaitá, Brazil. August 12, 2018. Burned pasture along the BR-319 highway near Humaitá, Amazonas state. The southern city of Amazonas is at the junction of BR-319 with the Trans-Amazonian highway which is the region with the highest rate of deforestation in the state. Inaugurated in 1976, the BR-319 has almost 900 km and is the only road link from Manaus to the rest of the country.