Fascism says nothing’s true, your daily life is not important, the facts that you think you understand are not important, all that matters is the myth—the myth of one nation that’s together, the mystical connection with the leader.

When we think of post-truth, we think it’s something new … actually what post-truth does is it paves the way for regime change. If we don’t have access to facts, we can’t trust each other. Without trust, there’s no law. Without law, there’s no democracy. So, if you want to rip the heart out of a democracy directly, what you do is you go after facts. And that’s what modern authoritarians do.

- Timothy Snyder, author of On Tyranny. Excerpt from The Daily Show appearance, 2017

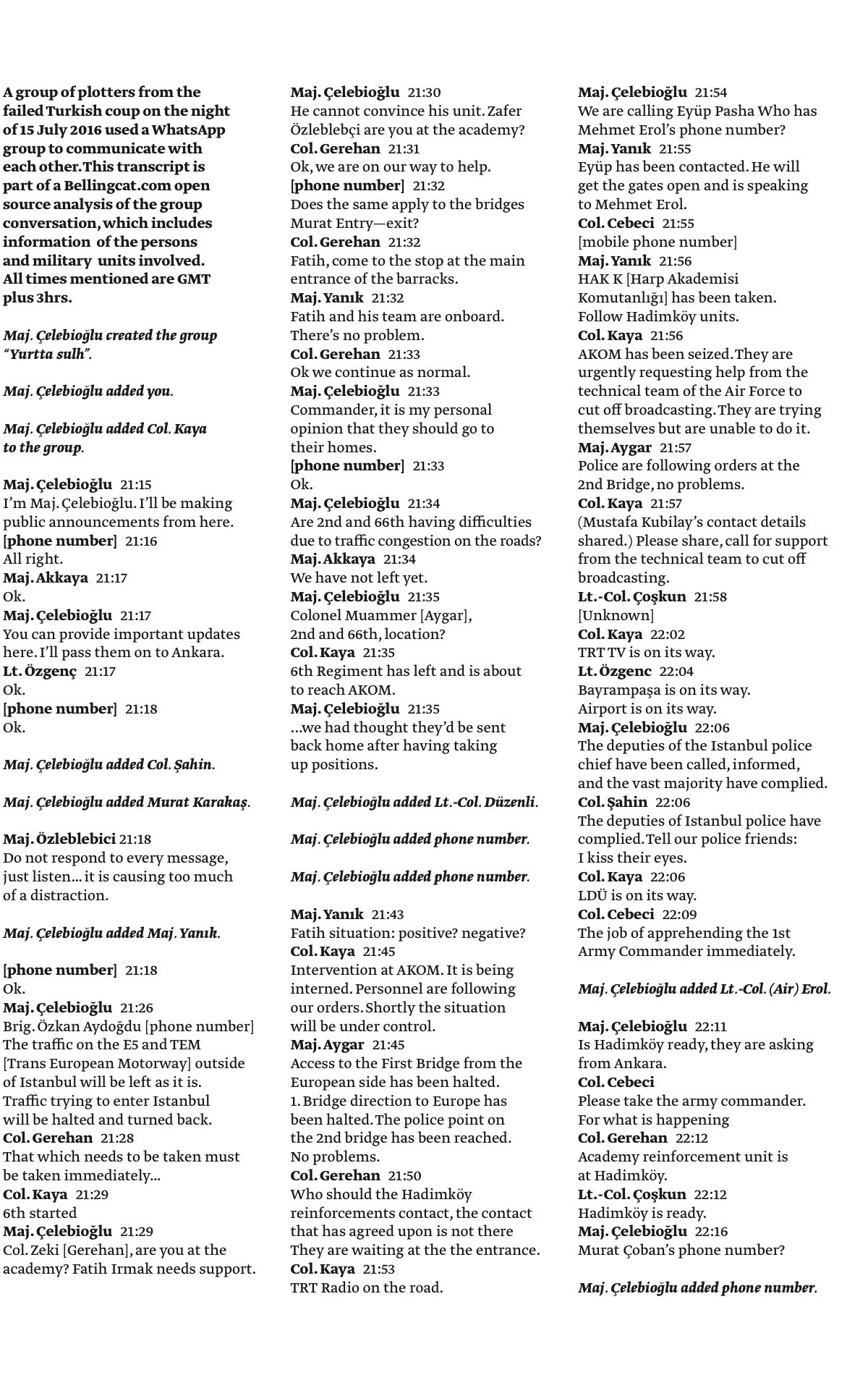

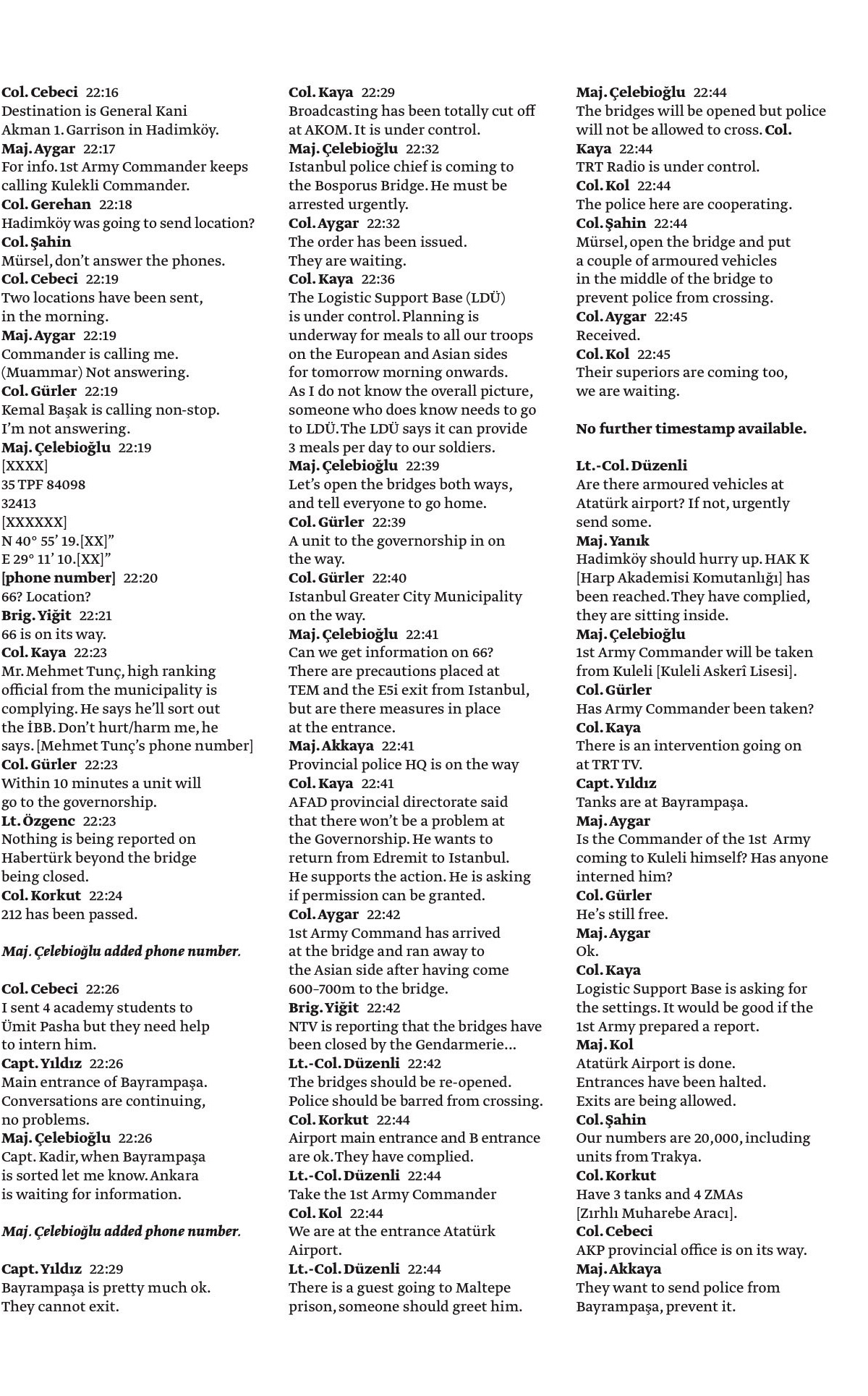

‘The parallel state’ is a term hijacked by Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and turned on its head, a rebranding, essentially, of the better-known ‘deep state.’ The modern Turkish deep state origins lie in the early days of the cold war when clandestine ‘stay behind’ units formed the foundation for a resistance movement in the event of an invasion and occupation by communist forces.

These forces were collectively called the OHD (Special Warfare Unit) and its members were all highly trained in intelligence gathering, tradecraft, assassination, sabotage, propaganda and other covert activities to destabilise a hostile regime. The communist invasion never came, but throughout the next sixty years, these units morphed and integrated into the police, judiciary, civil service, military and media.

At a raucous televised congress of the AK Parti (Justice and Development Party) in the southern town of Kahramanmaraş, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was asking the crowd for support of Turkish troops in on-going military operations. A six-year-old girl dressed in military uniform suddenly caught his eye and he called out to her, ‘Look, look, look, what is there? Girl, what are you doing there?’

The young girl, giving a military salute, stood ramrod straight in the audience, but her lips were trembling. Erdoğan’s aides scrambled to help the girl through the crowd to the stage. ‘We have our maroon berets here, but maroon berets never cry,’ he said, referencing the uniform worn by the Turkish Special Operations Forces fighting Kurdish YPG units in Syria’s northern Afrin Region. His supporters cheered loudly, ‘Chief! Take us to Afrin!’

The girl, by then in a flood of tears, stood stunned next to the President, who kissed her on both cheeks. ‘She has a Turkish flag in her pocket too … If she becomes a martyr, God willing, she will be wrapped with it’ he continued, ‘She is ready for everything, isn’t she?’

The girl replied, ‘Yes.’

The President then kissed her face again and let her go. He continued his speech at the congress rally, promising to protect Turkey’s borders and crush terrorism. He recited Turkish poetry—conjuring glories of Turkey’s past, listed the number of enemies killed, and asked the crowd to send prayers to families of recent martyrs.

As Tayyip Erdoğan rose to power from the early 2000s, he was increasingly, and sometimes rightly, convinced that he was being undermined by followers of his former ally, Fethullah Gülen, currently in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania. Gülen, a cleric and preacher of a more moderate, inclusive and scientific form of Islam, fled Turkey in the late 1990s fearing arrest from the military rulers at the time.

By 2012 Gülen’s followers—now numbering in the millions—had infiltrated every institution within the Turkish State. To supporters of Erdoğan, this secret politicised, bureaucratic cabal, were all part of a traitorous ‘parallel state’ that could and would be blamed for any of Erdoğan’s mishaps and Turkey’s ills.

A once uniquely Turkish phrase, ‘the parallel state’ has become a byword for power grabs, populist rhetoric, and a police state on the hunt for an unfixed yet ever-present enemy, recalling Western politicians’ endless invocations of ‘terrorist’ forces at work. With factious political movements on the rise from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond, the work has taken on a particular potency in its focus on Turkey as a model for the ways in which authoritarianism might be sewn almost imperceptibly into the fabric of a society; the deliberate shattering of citizens’ sense of security, community, and ability to distinguish between fact and fiction ensures only one state-approved narrative prevails.

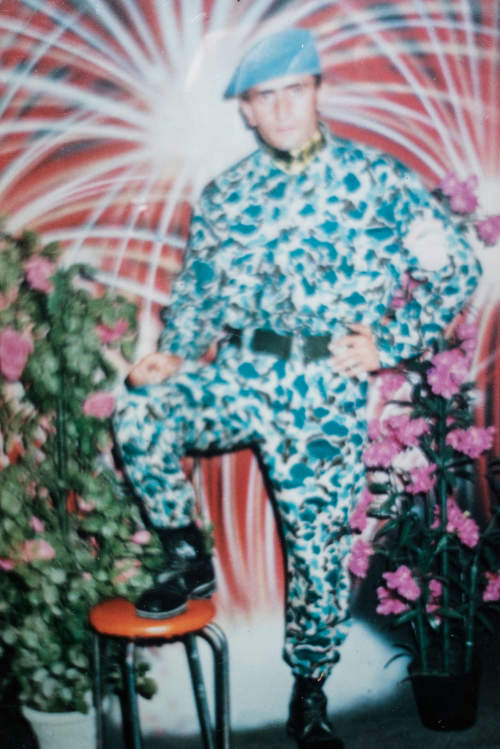

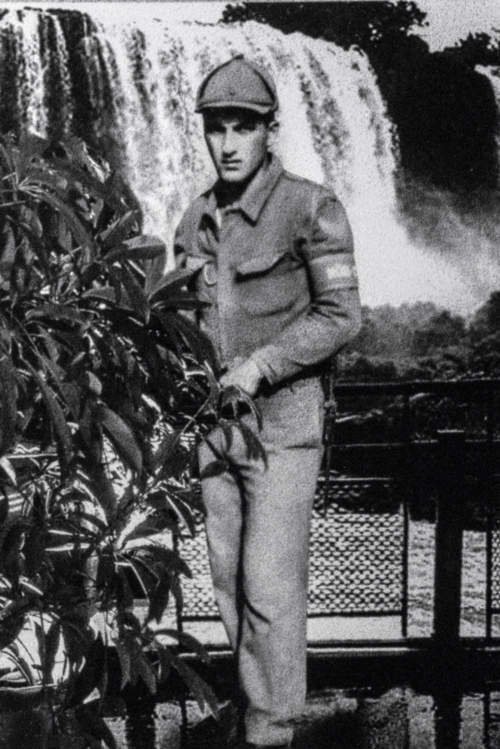

The Parallel State encompasses the idealistic Gezi Park protests of 2013 to the failed coup attempt in 2016 and subsequent purges—the government’s crackdown on suspected adversaries. Intermixed with photographs of those cataclysmic events are images from the sets of Turkish soap operas, houses of mirrors in which the country’s recent past occasionally comes into view.

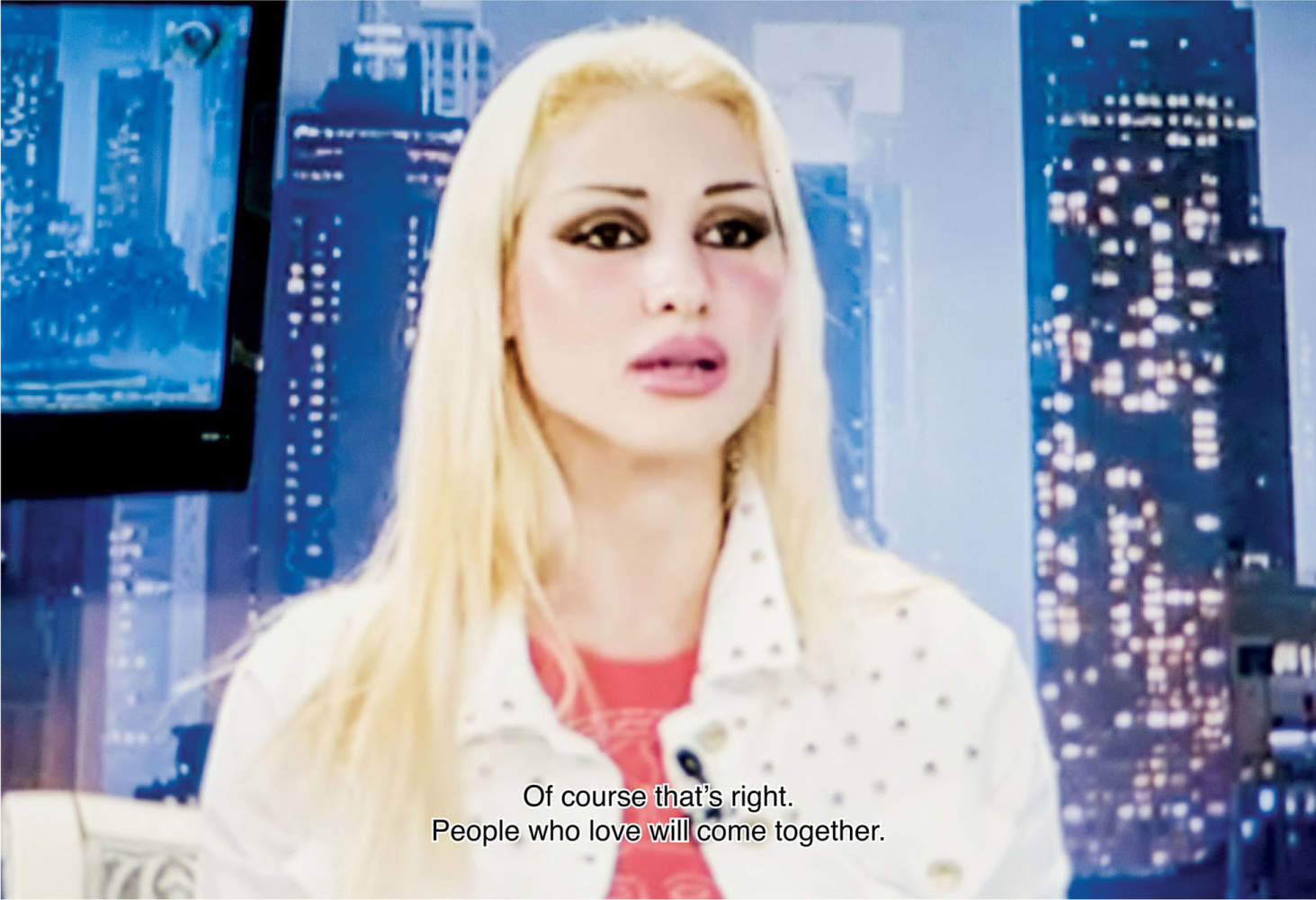

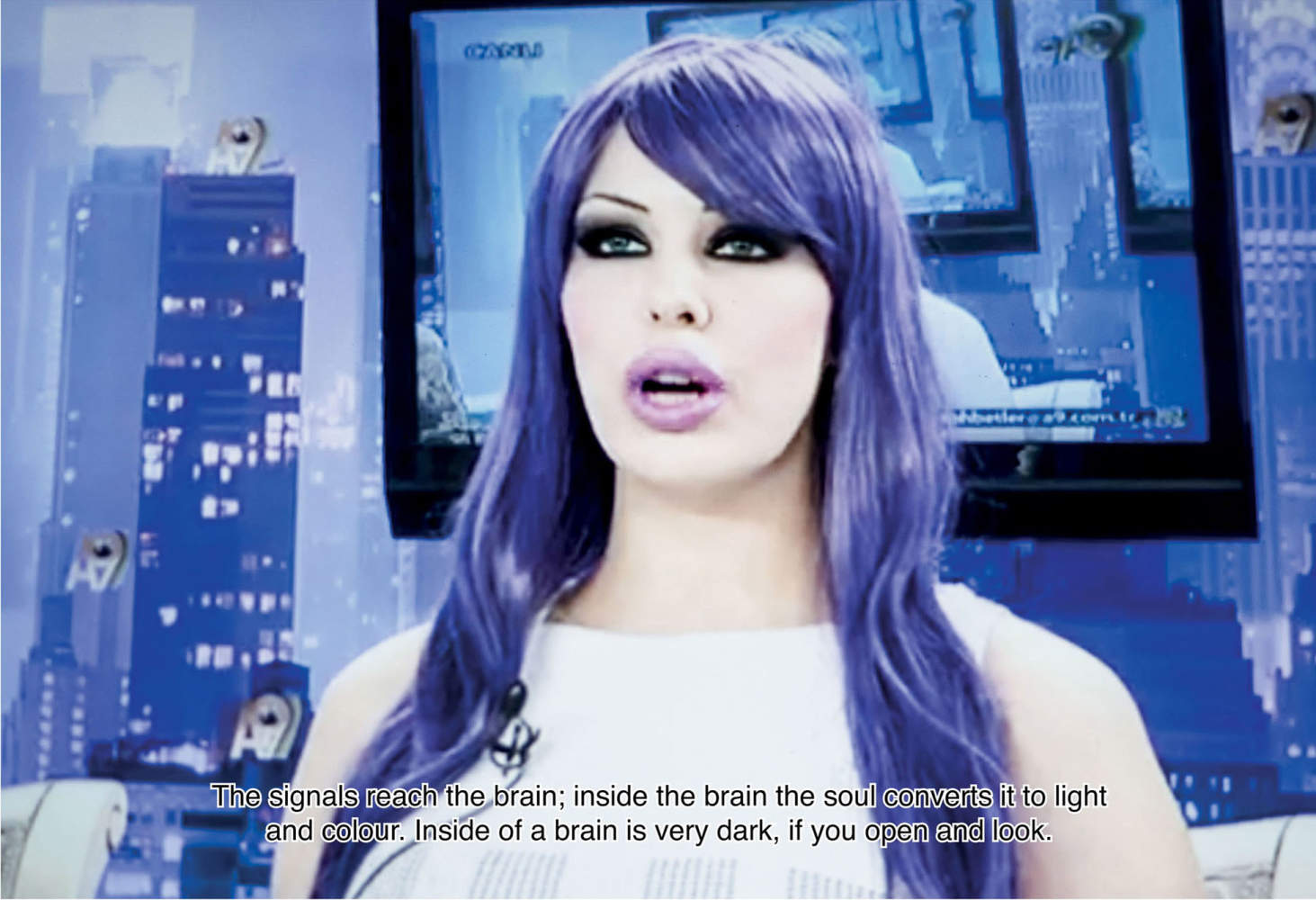

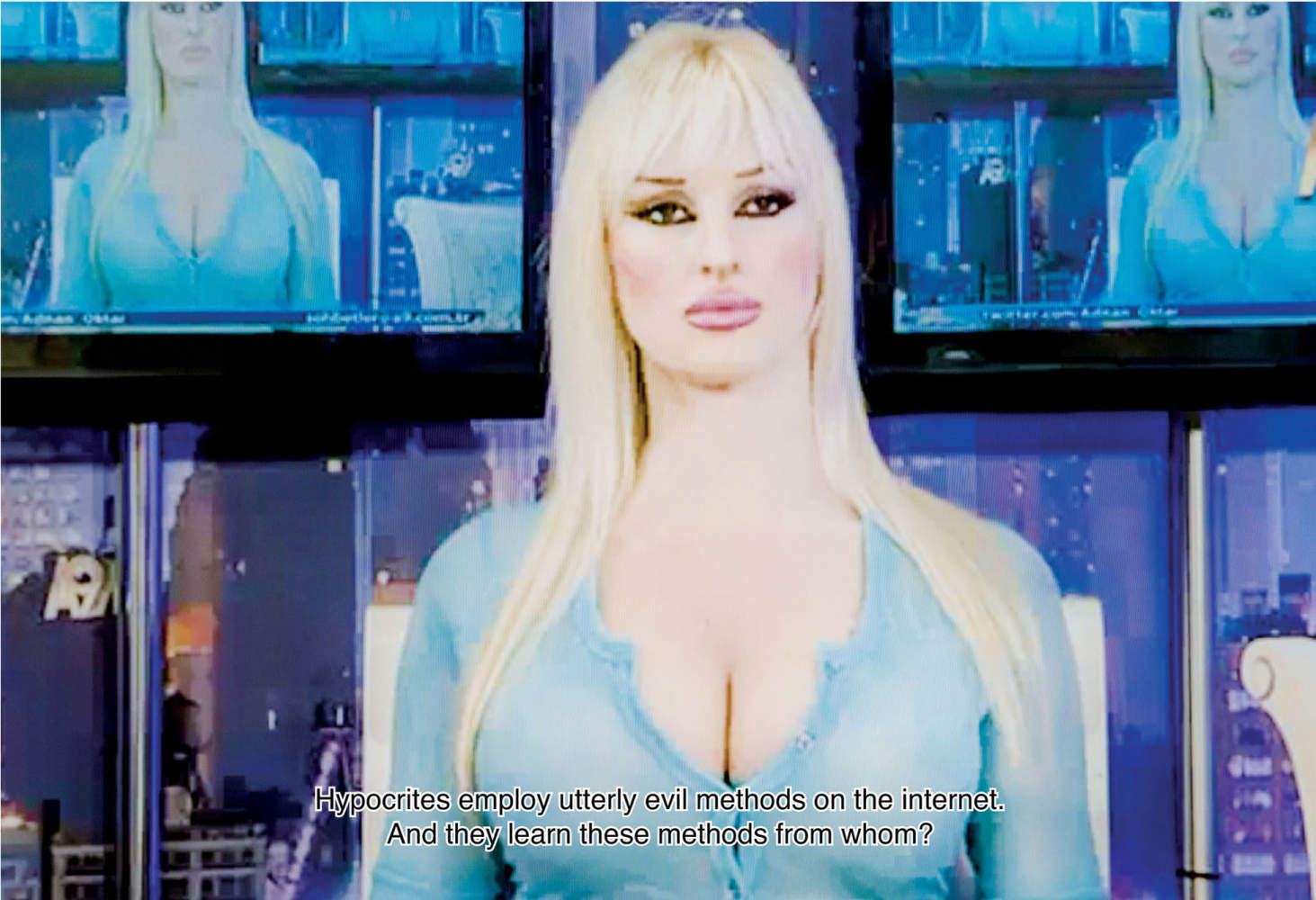

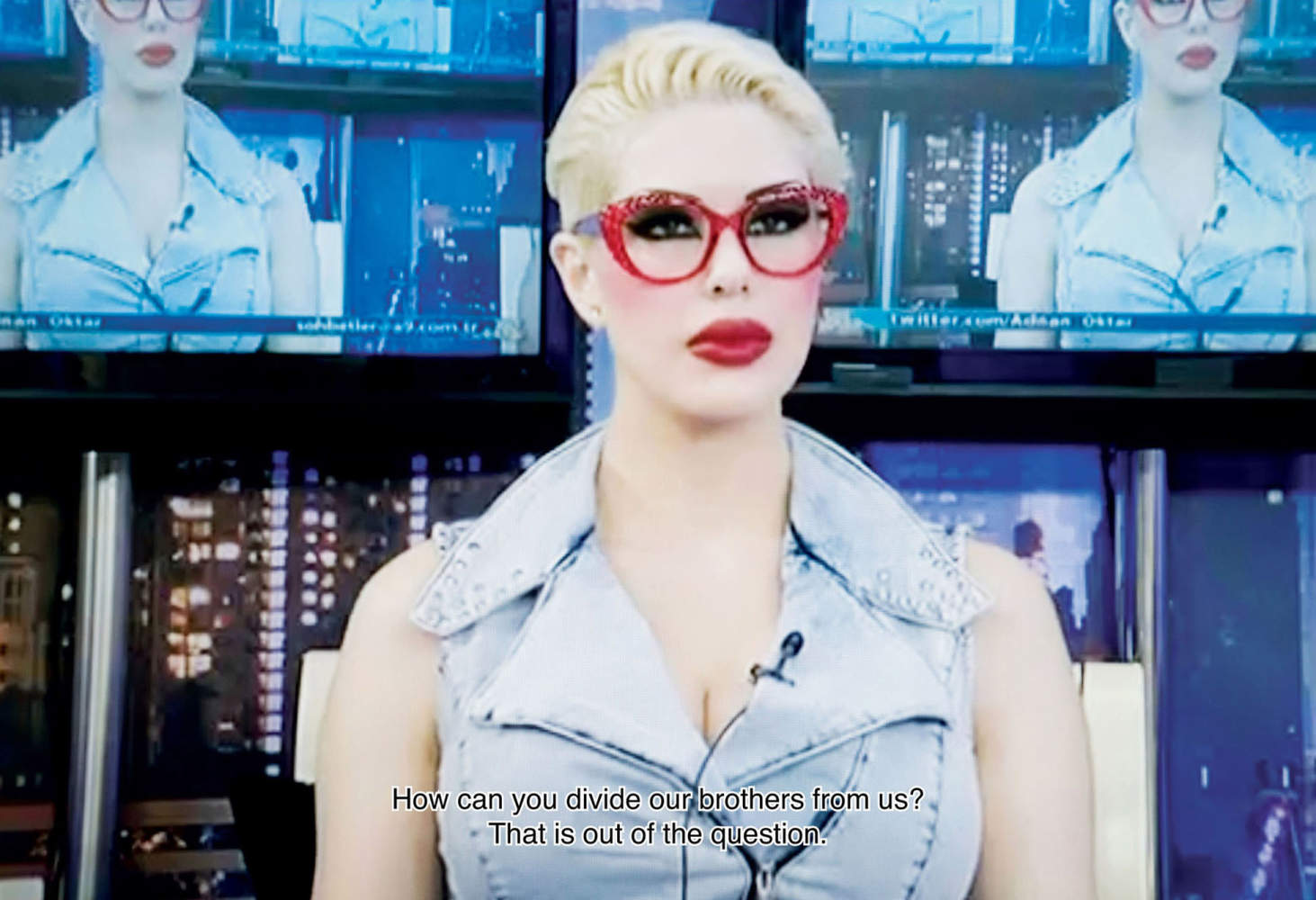

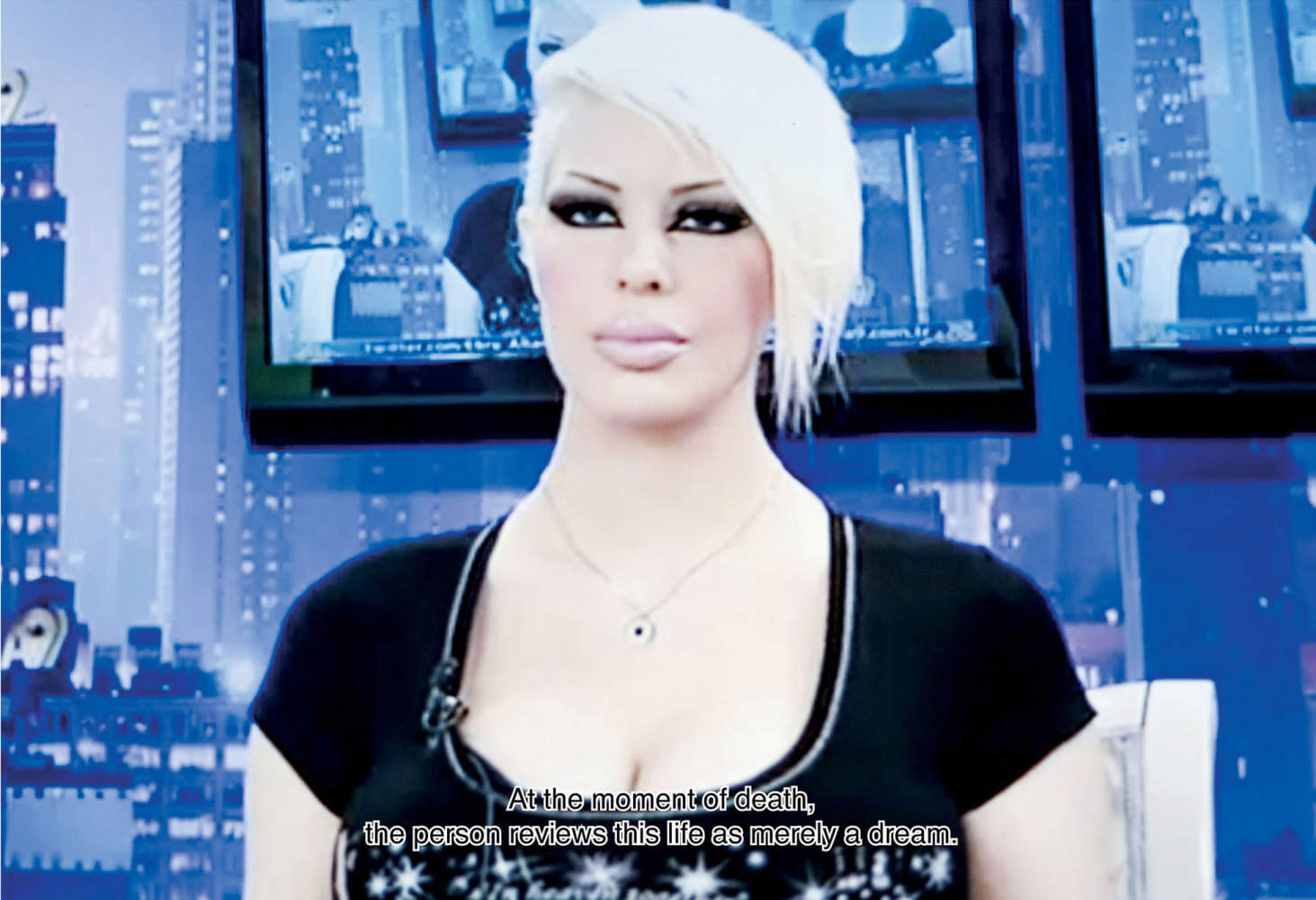

Adnan Oktar is the most notorious cult leader in Turkey. Beginning in the 1980s, the Muslim creationist introduced the world to his bizarre take on Islamic religion – including his fierce opposition to the theory of evolution – when he published his book The Atlas of Creation. Oktar refers to his cadre of devoted women as ‘kittens.’ At his behest, the ‘kittens’ shirk hijabs and traditional dress. Instead, they wear designer outfits, apply heavy makeup, and undergo plastic surgery. They also happen to be wealthy socialites. Oktar’s televangelism is a bewildering spectacle that challenges normal expectations of what the Islamic debate should be and has sparked ridicule and indignation in equal measure.

Critics call his broadcasts ‘a sexed-up Disney version of Islam.’ But what makes his shows so unique is the way he manages to use sex as a device to preach theories on Islam. Cosmetically enhanced, platinum-haired women swoon around him and refer to him as ‘master,’ while wearing tight t-shirts emblazoned with phrases like I read the Quran. Oktar and his followers are trying to usher in what they call the new face of modern Islam. With their own TV network, A9, they broadcast their views and through the network’s publishing arm, Oktar has published over 300 books, all written under his pen name, Harun Yahya. Many of the books argue that Darwin’s theory of evolution is at the root of global terrorism.

On the morning of 11th July 2018, Oktar and 155 of his ‘kittens’ were arrested by officers from the financial crimes branch department of the Turkish Police. The charges put against them included the formation of

a criminal gang, tax fraud, terrorism and sexual abuse. Ammunition and more than fifty guns were seized during the series of raids. Before being led away in handcuffs, Oktar told journalists that the allegations made against him were lies and ‘a game by the British deep state.’ He added ‘… British intelligence has long wanted an operation to be launched on us. A delegation was sent to Turkey in this regard. This request was conveyed to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during his recent visit to the UK.’

As of the date of this publication, Adnan Oktar was still in prison and one of his ‘most senior kittens’ has agreed to cooperate with prosecutors in a plea deal.

TV shows that previously exported a simultaneously nostalgic and socially progressive vision of Turkey across the Arab world—with tales of sultans, harems and star-crossed lovers—have since refocused their storylines to emphasize Turkish military and political power plots by deep state operatives, collusion by foreign powers, and terrorist attacks by the Kurdish PKK and Islamic State.

History is not connected with events, but with processes. Processes are things which do not begin and do not end but turn into one another … There are in history, no beginnings and no ending.

– R.G Collingwood

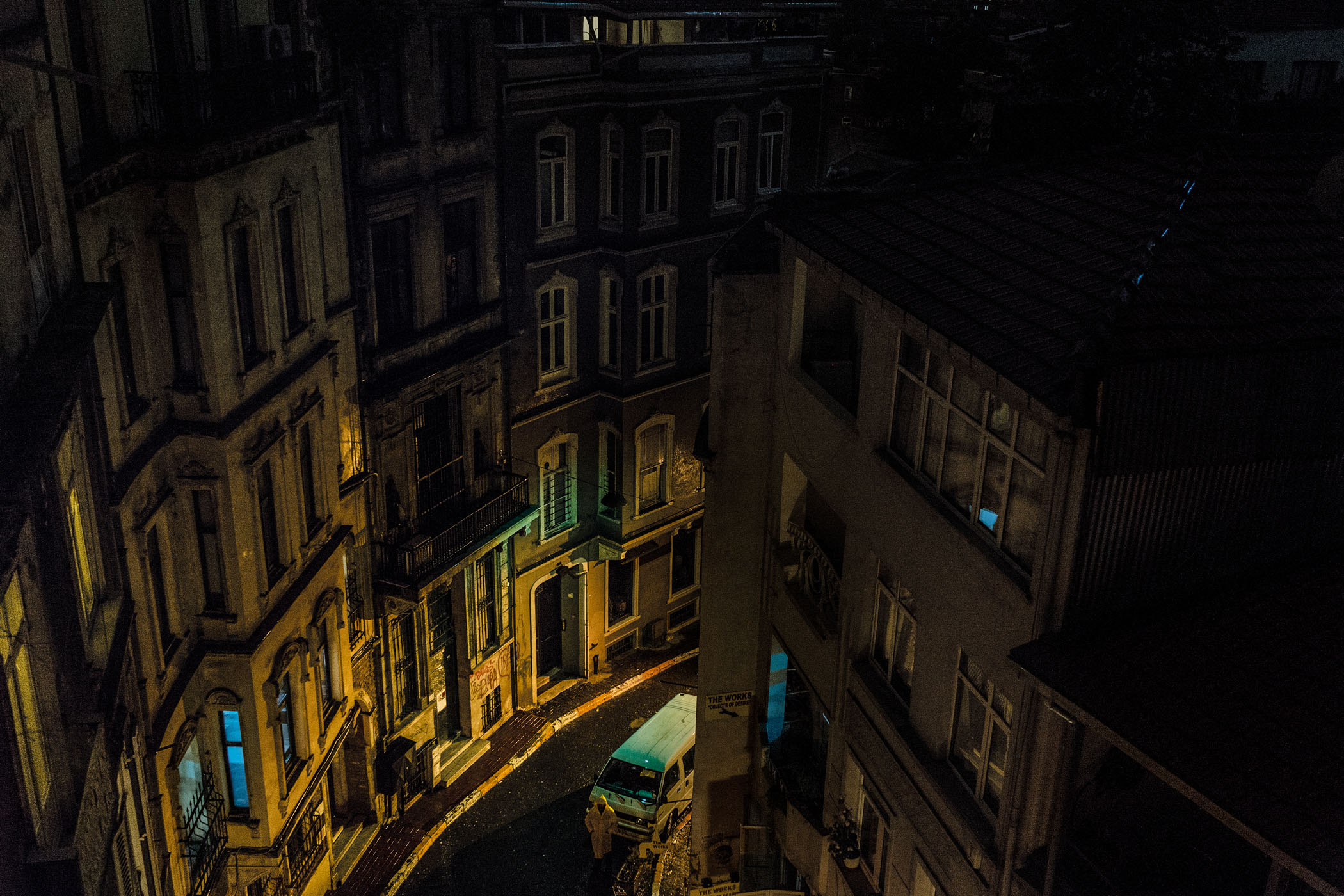

I was in Turkey to reclaim some semblance of normalcy after months of operations and rehab following a near fatal accident caused by an explosion while working in Libya. A friend’s offer of a flat in downtown Istanbul was the lifeline I needed. In Istanbul, some friends offered to help me get on the set of a popular Turkish TV soap opera. During my time working in the Arab world, I had long been fascinated by these extravagant shows – adored everywhere from the Balkans to Indonesia. I was only supposed to shoot one day, but ended up staying for nearly two years. I revelled in my new-found ability to film inside homes – in living rooms and bedrooms. I was able to photograph women in situations that had always been off-limits to me. I was getting to know a country through its drama and fictional storylines instead of its conflicts.

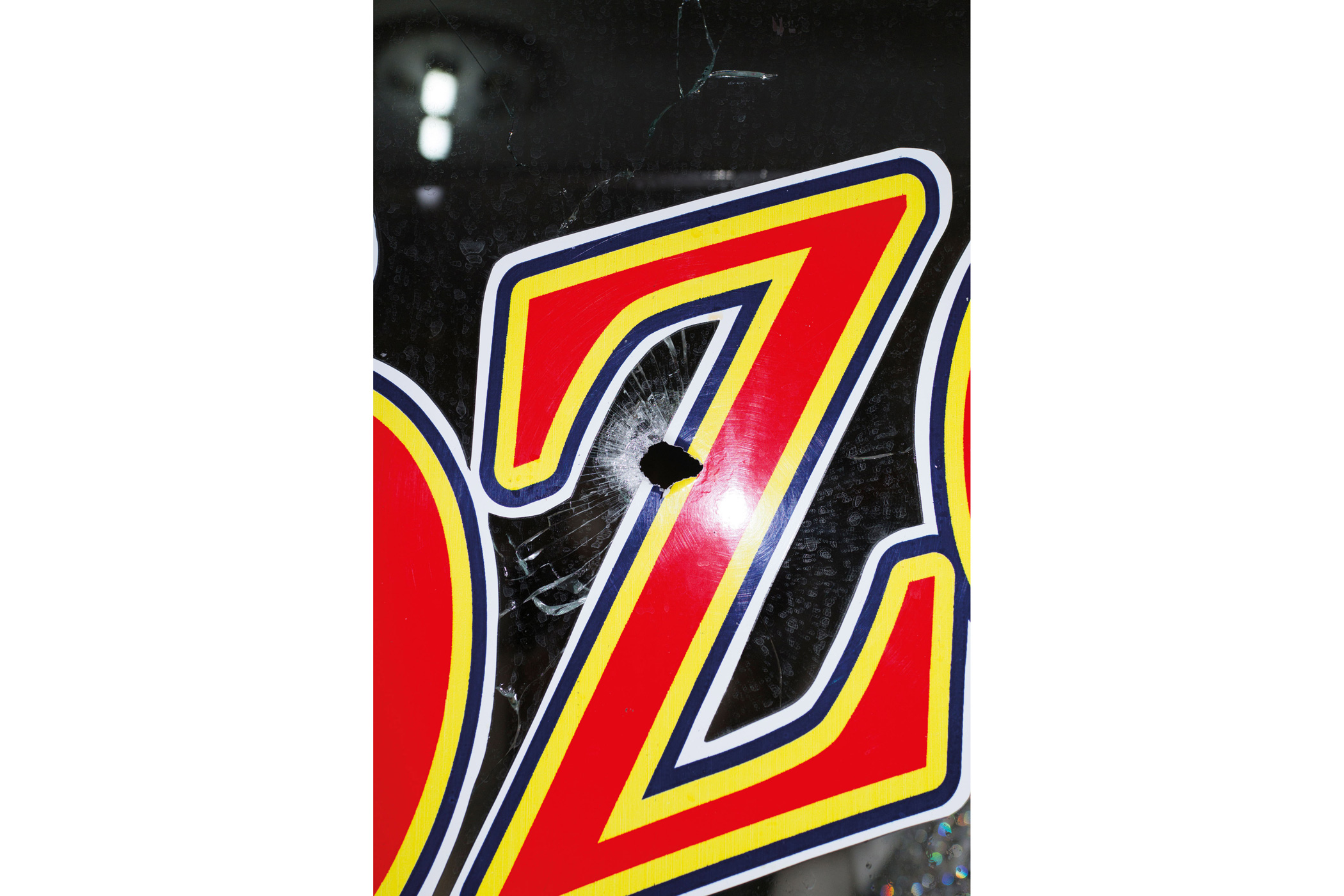

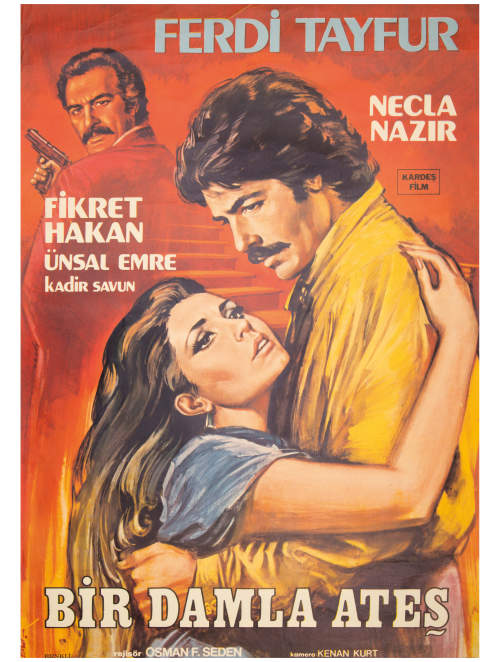

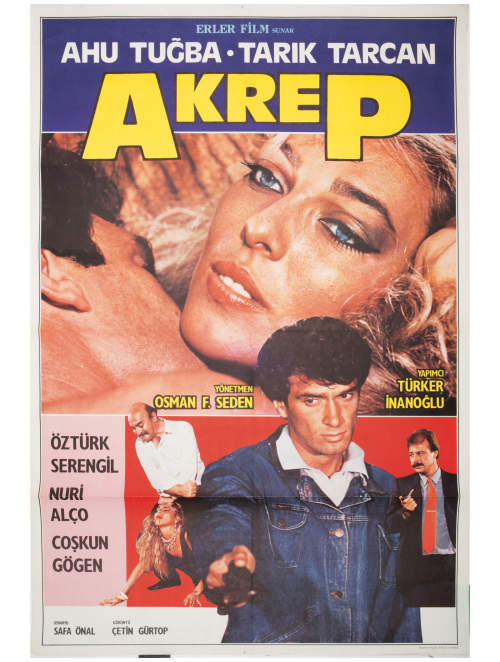

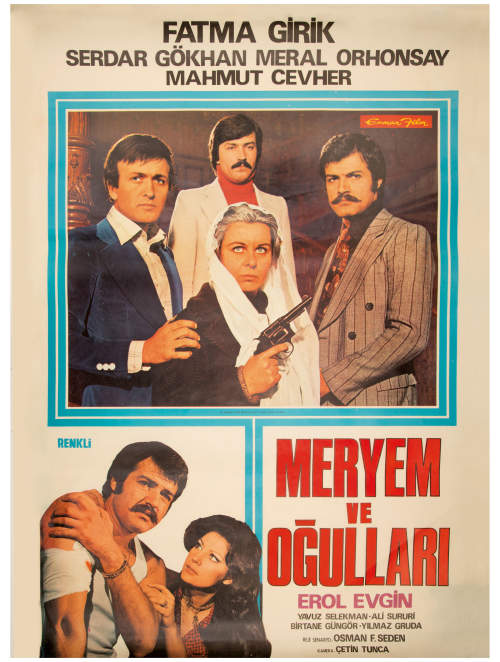

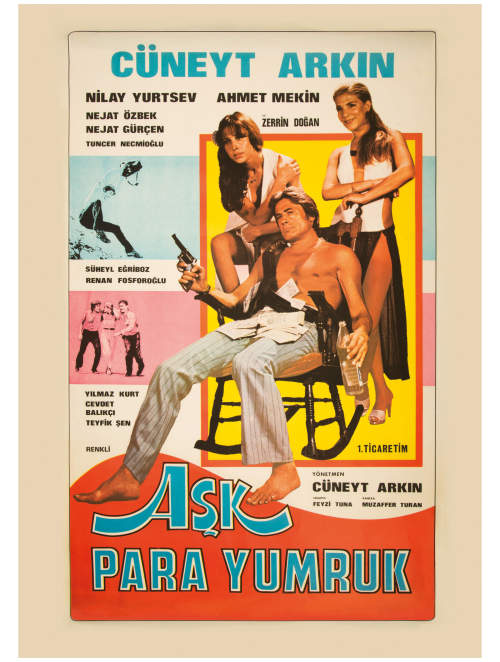

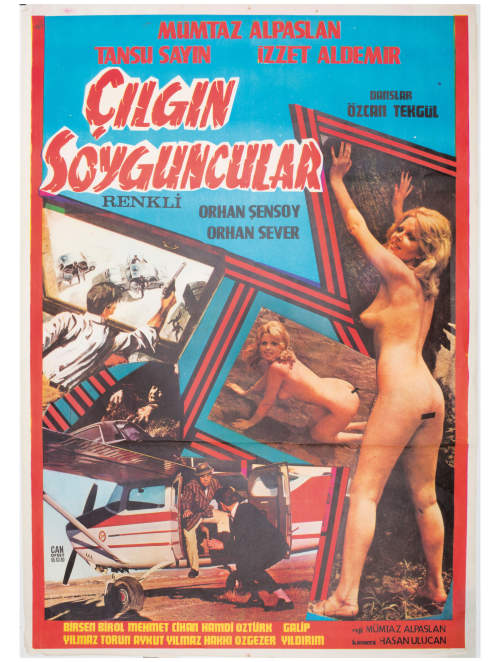

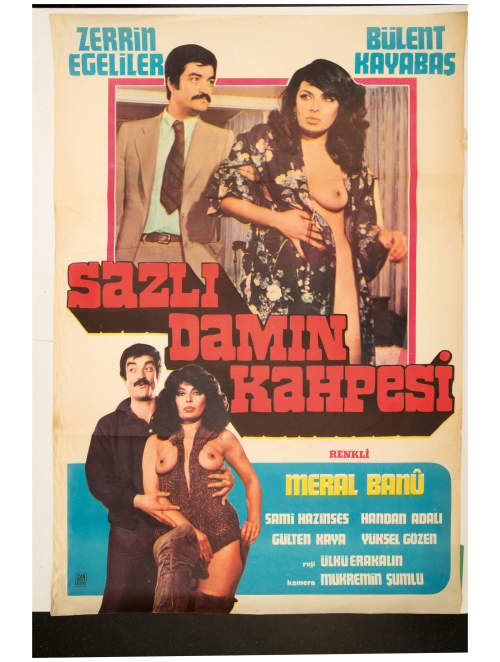

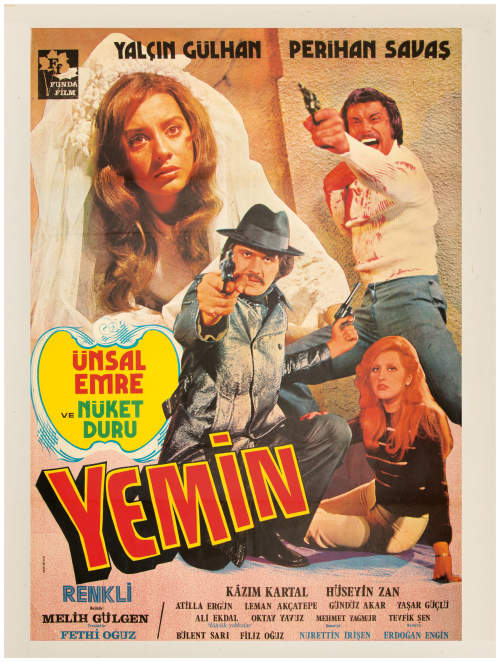

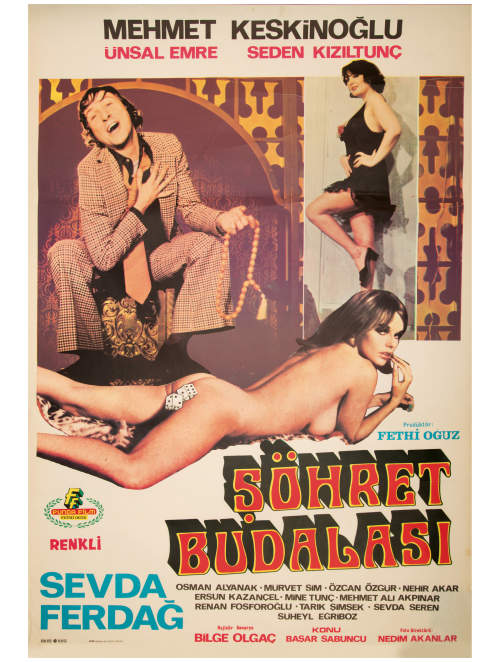

I was changing as a photographer too – immersing myself in a version of reality; a parallel state of mind. I found a new way to relate to the medium I loved by spending time in a fictitious world, full of fantasy and drama. But as the years passed, events turned darker and Turkey itself began to resemble a horror movie. The country was consumed with violence: fighting in the east, the rise of ISIS, the refugee crisis, suicide bombings in airports and on the streets. Istanbul was no longer the city of dreams it once was, but a city of nightmares. Each month brought a seemingly bigger and uglier event than the one before. During this time, I began collecting movie posters as I moved around the country. Some came from bookshops, some from markets and other times friends would tip me off about a particular rare poster owned by a friend of a friend.

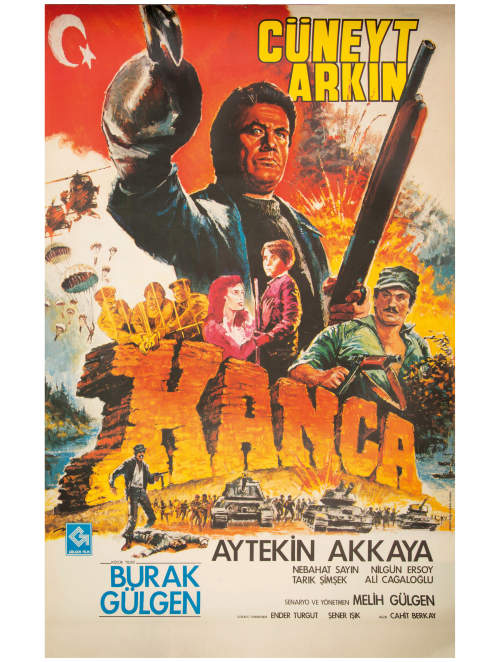

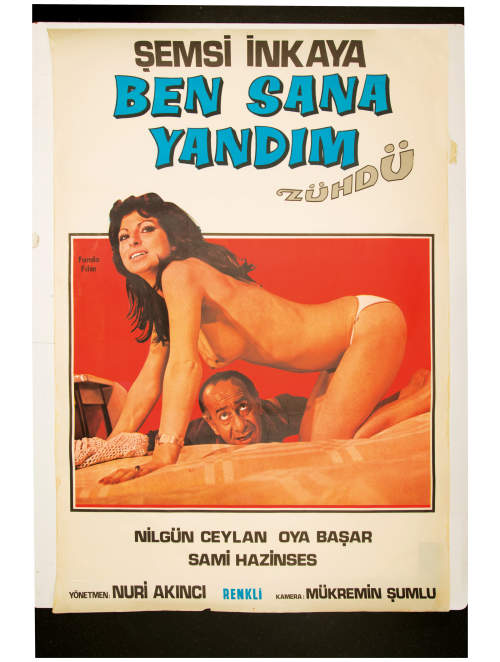

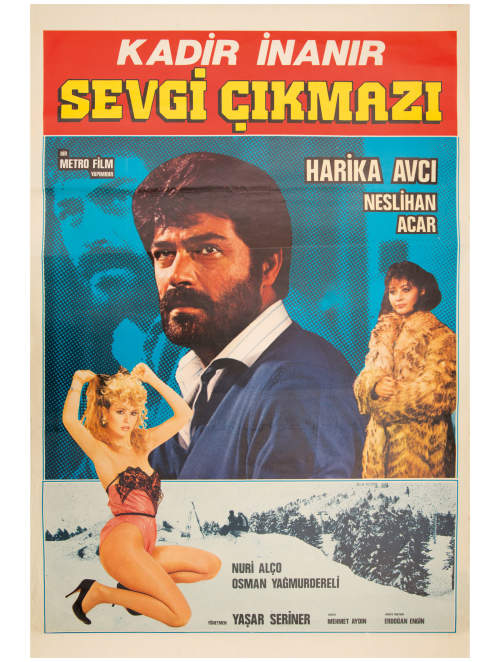

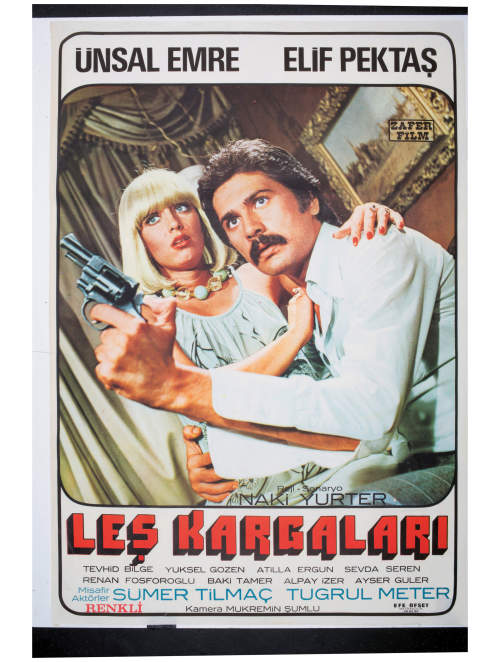

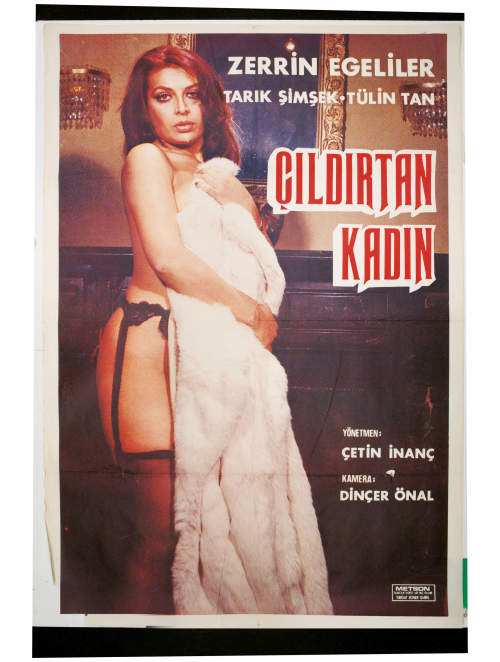

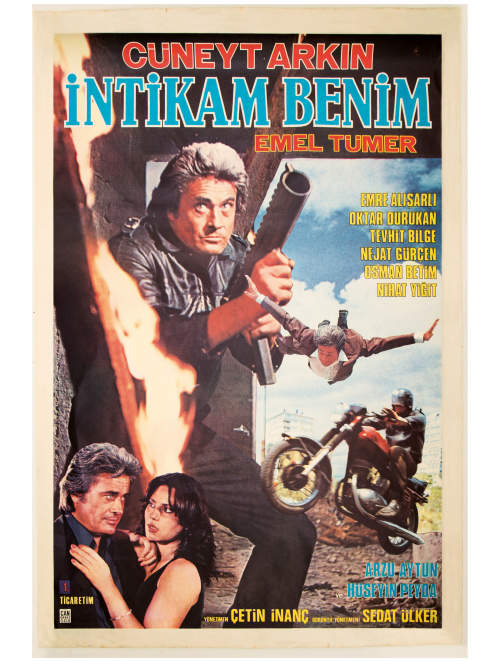

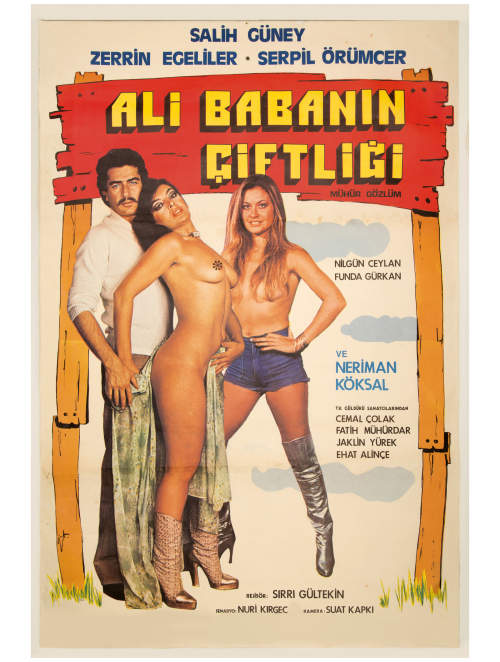

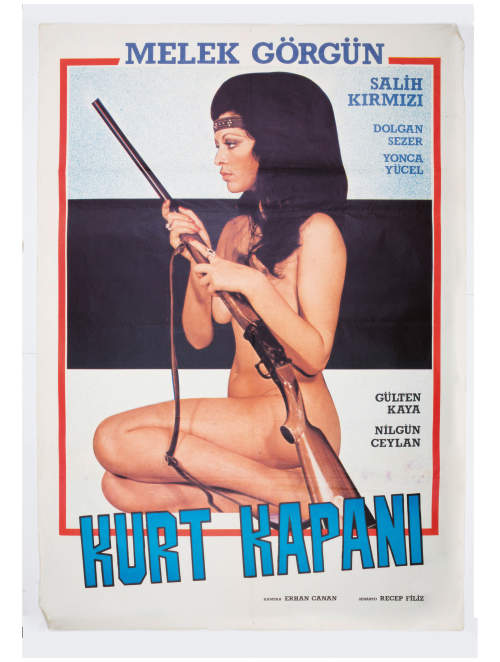

The movies in these posters were all made in the late 1970s and 80s, a period in which Turkey lurched from a political crisis to a military coup, to a purge and back into a political crisis. It was also a time when the country was wrestling with its own identity; was it secular? Was it left wing or was it right wing? Was it conservative? Was it a democracy? The movies reflected that quest for meaning. Often they were crass, low budget re-makes of Hollywood or Italian films. Action heroes, in the style of Sylvester Stallone, got a Turkish version, in the name of square jawed Cüneyt Arkin who saved Turkish cities from marauding terrorists and coup-plotting generals.

When looking at the current culture and politics of Turkey, the content of the posters was remarkable. The 1970s were a salacious time for world cinema and Turkey was no exception. A coup by Turkey’s military in the autumn of 1980 didn’t quite put an end to the risqué and erotic films that were being produced on Yeşilçam Street, but the subsequent crackdown of leftists and liberals certainly dented the output. Though the censorship put in place by the new military rulers was relatively tolerant of soft porn, it was far less lenient to anyone who dared create politically driven entertainment.

Outside of the film industry, during the 1980s, a new wave of liberal feminism arrived in Turkey reclaiming women’s sexual identities and desires outside the family home. Even so, it’s hard to look at these movies and see a correlation – women in Turkey clearly had a long way to go until their films showed more nuanced female characters: the victim, the siren, the arm candy, the mistress. Conservative, pious women were not represented.

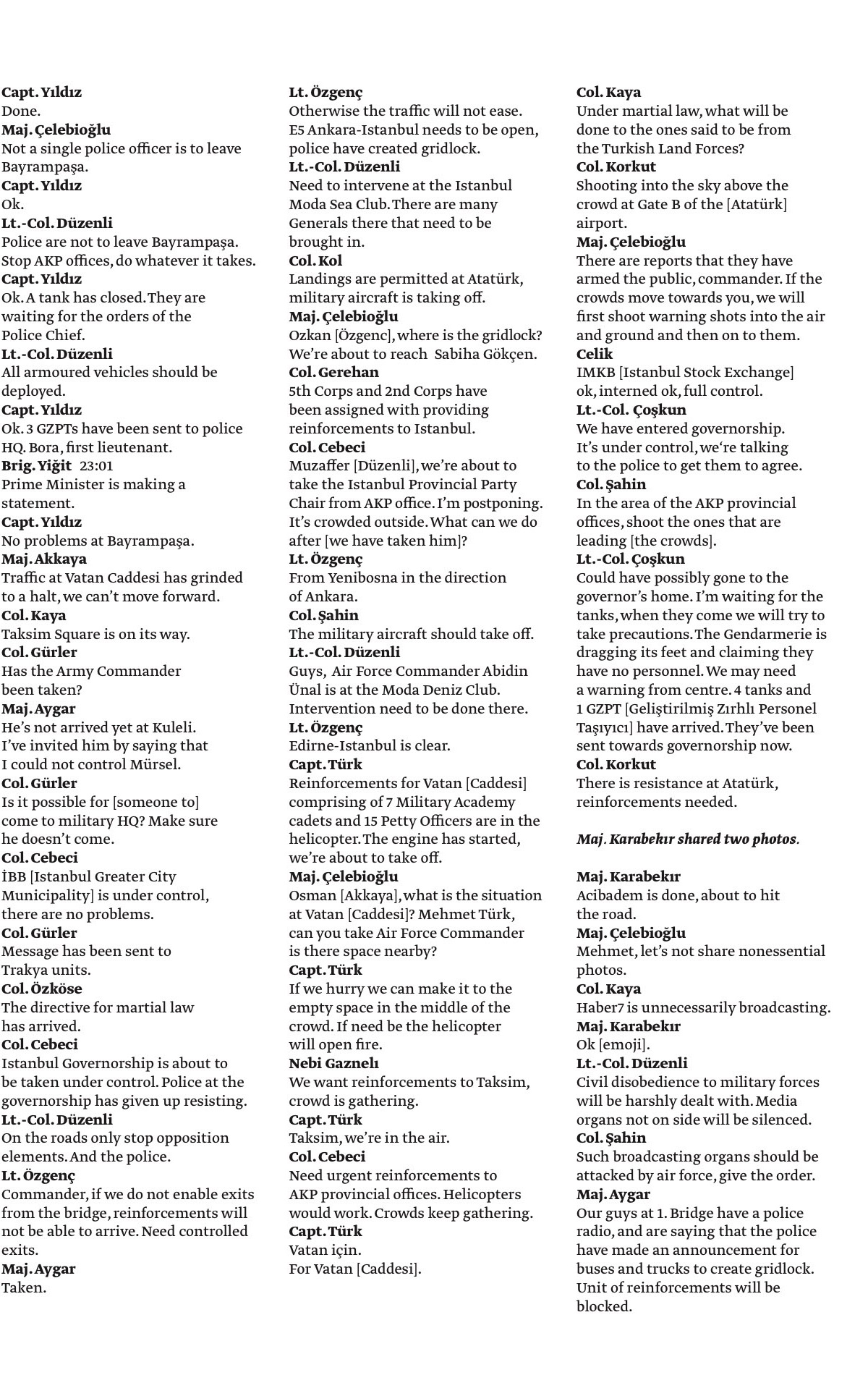

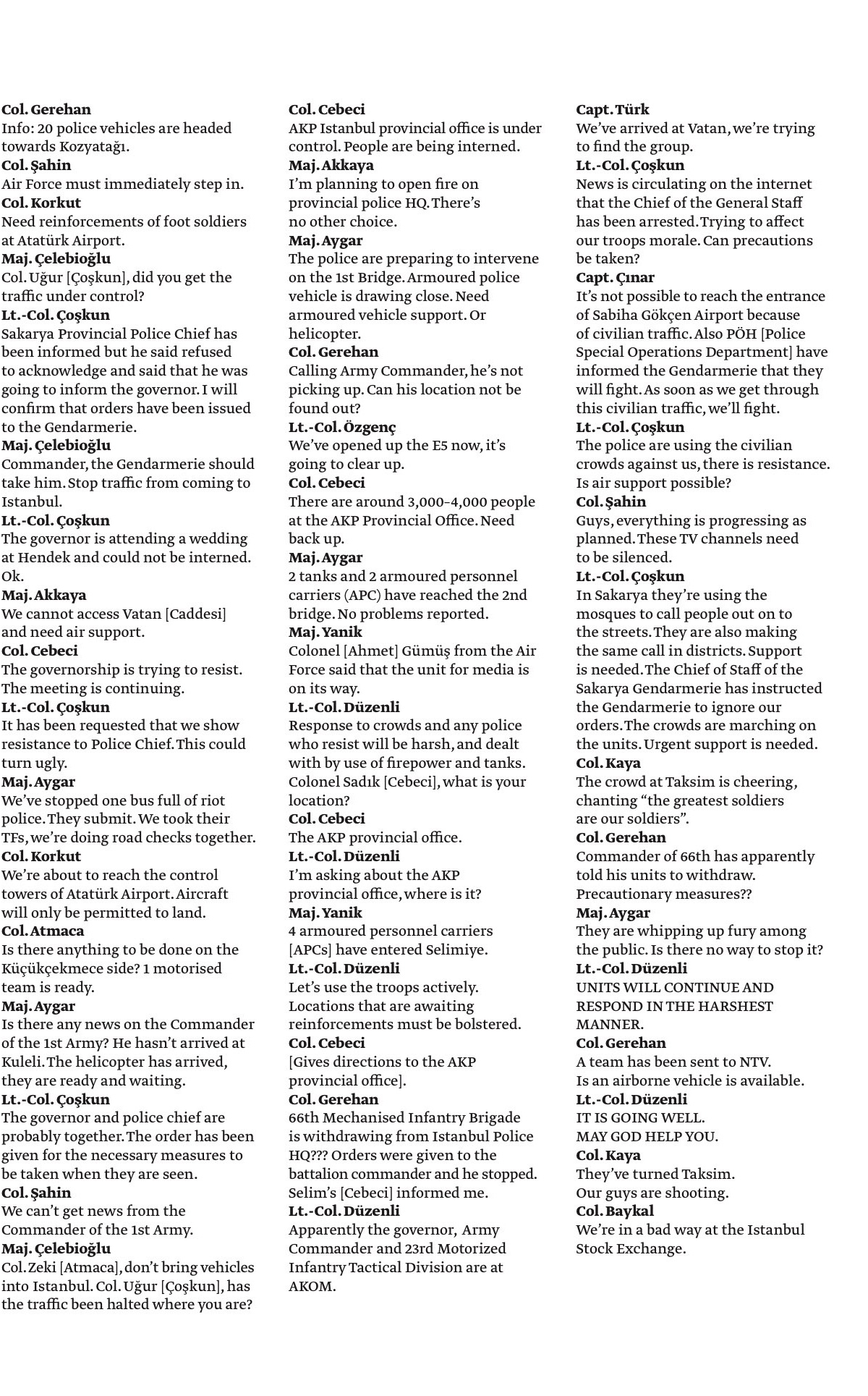

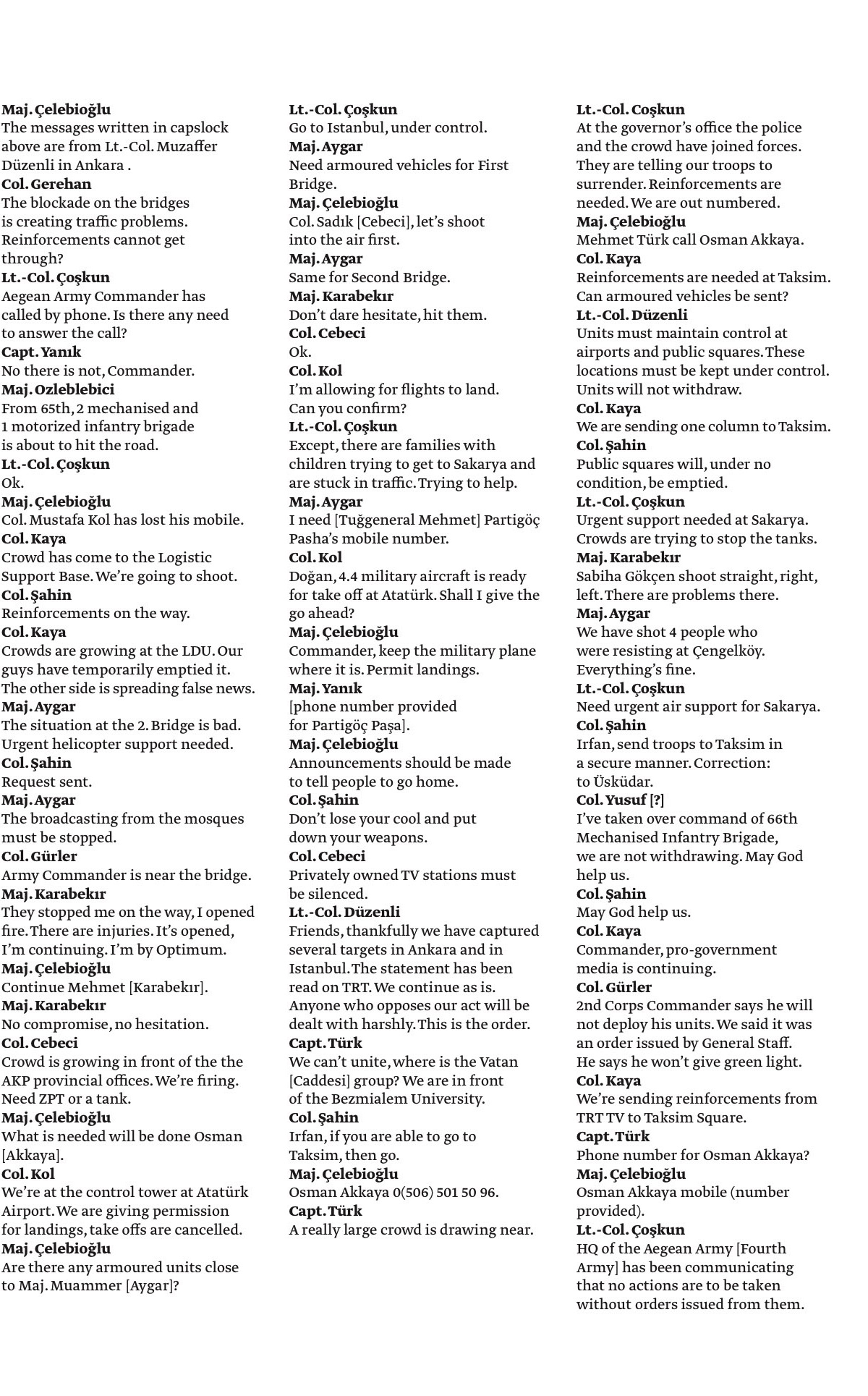

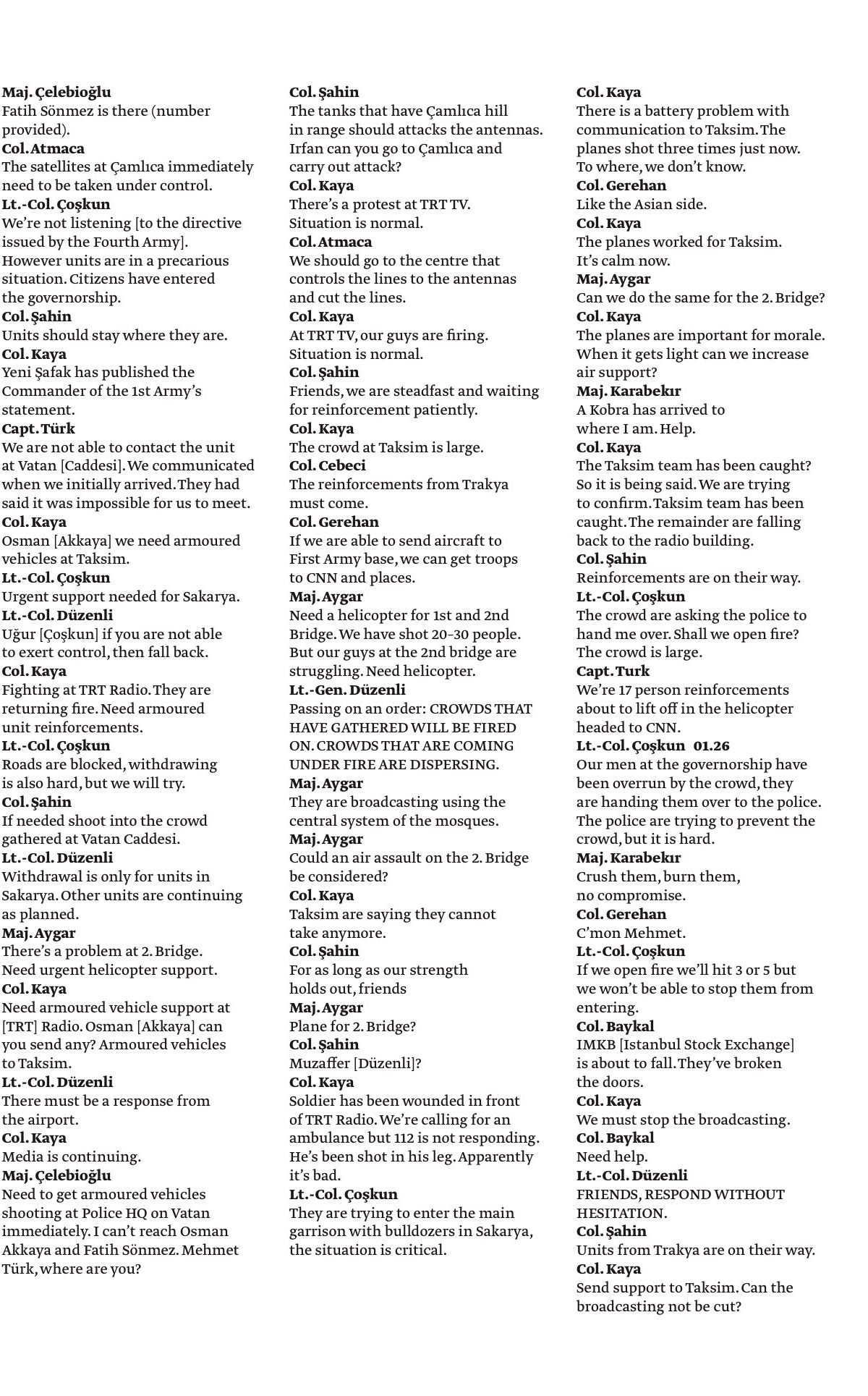

As I stood alongside a tank the day after a failed military coup in July 2016 and watched my twitter feed replay CCTV footage of helicopter gunships strafe and bomb civilians in the nation’s capital, the analogy between Hollywood fiction and reality was all too apparent. I took a walk the following afternoon to one of my favourite booksellers and passed municipality workers setting up for a ‘demokrasi’ festival – erecting huge soundstages and outdoor cinema screens to display mobile phone footage of the ‘heroic patriots’ who stood up to tanks the previous night.

I rifled through the bookseller’s second hand selection, my attention turned to some dust-covered boxes of Yeşilçam Street movie posters. My eye caught the rugged, thousand-yard stare of Cüneyt Arkin, shotgun in hand, standing up to men in uniform. The scene depicted paratroopers falling from the sky, helicopter gunships, mushroom clouds of explosions and tanks marauding through the streets. As I got out my wallet to pay, the bookseller pursed his lips and tutted while pointing to the illustration of Cüneyt Arkin. ‘That’s not Cüneyt Arkin,’ he said, ‘that is Tayyip Erdoğan.’

As social media assumes an increasingly influential role in contemporary conflict, new ‘virtual battlefields’ on mobile, computer and television screens have become as relevant as the physical ones. The Parallel State strives to address the complexity of capturing ‘authentic’ moments while confronted with media-conscious subjects acutely aware of how to stage a narrative for easiest consumption.

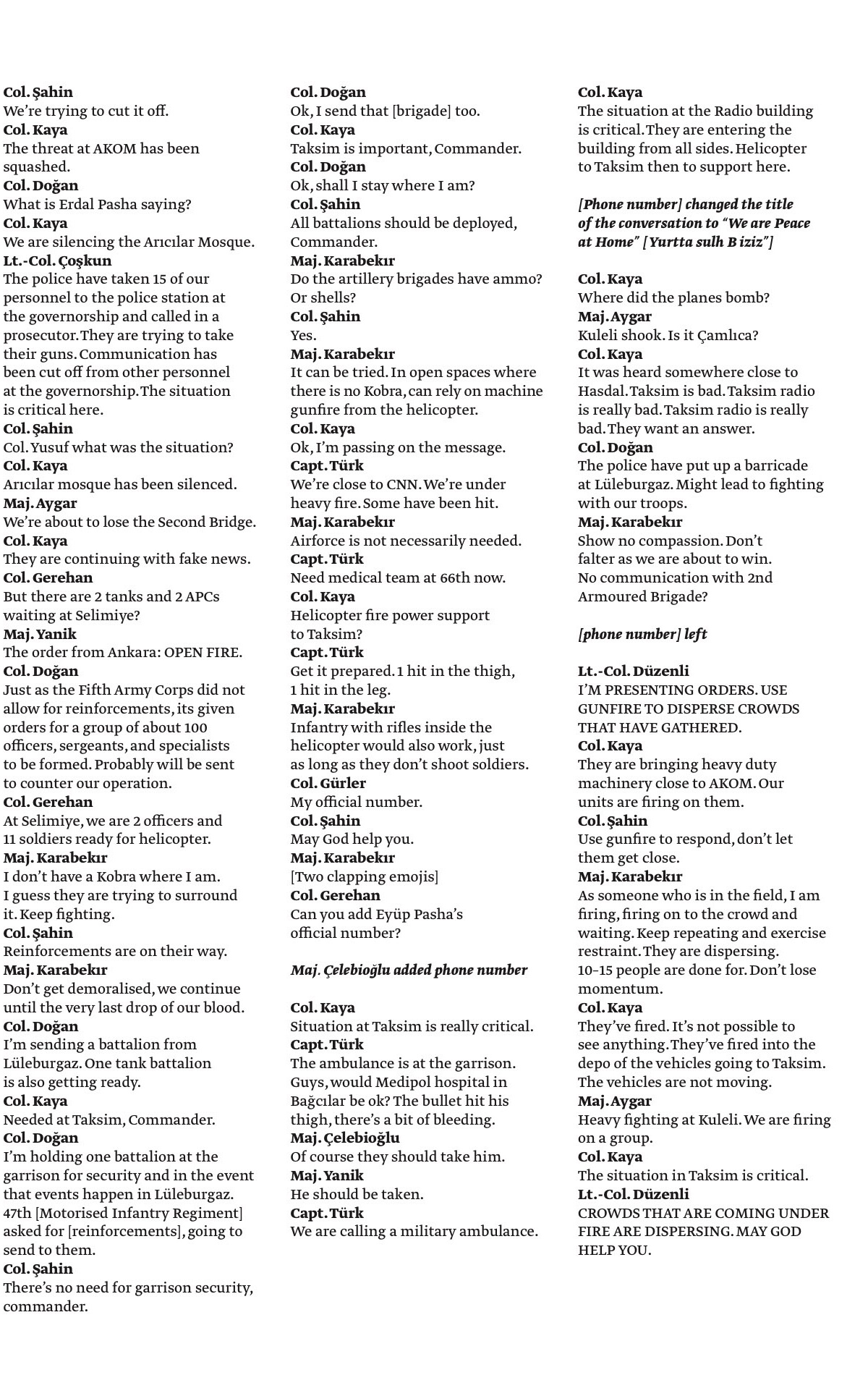

Acknowledging the danger in any individual claiming the status of ‘truth-teller,’ The Parallel State serves as a timely vision of how authoritarianism thrives in a society plagued by doubt and divisive falsehoods, segregated into heroes and villains, and deprived of access to facts.