In June 2025, India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated a new railway line that for the first time connects New Delhi to Kashmir. Carving through the Himalayas with its 36 tunnels and 943 bridges, it spans 272 kilometers of railway tracks. Officials hailed the project as an engineering triumph and and economic boost for the valley. But for many Kashmiris, the gleaming carriages symbolise something darker: an artery of military control and cultural assimilation.

REASI, JAMMU & KASHMIR: An indian married couple Kamal (58) and Rajbhadia (55) Badia are on a holiday trip to Kashmir. They have taken the train on the newly inaugrated line into Kashmir for the fables views and have turned their seats to face the window (which is a feature specific to the train), as they cross the Anji Khan Railway Bridge.

"This is an example of India's outstanding innovation," says Kamal Badia, first time passenger with his wife on the Vande Bharat Express, as banks of mist drift between the mountains. On the tape blaring from the speakers, an equally enthusiastic woman's voice sounds: "the bridge is even higher than the Eiffel Tower." The Chenab Rail Bridge on the new line is the highest railway bridge in the world at 359 metres.

JAMMU, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: A high speed train arrives at the platform at Jammu central station, before making its way to Katra, from where a similar train will transport travellers to Srinagar in Kashmir.

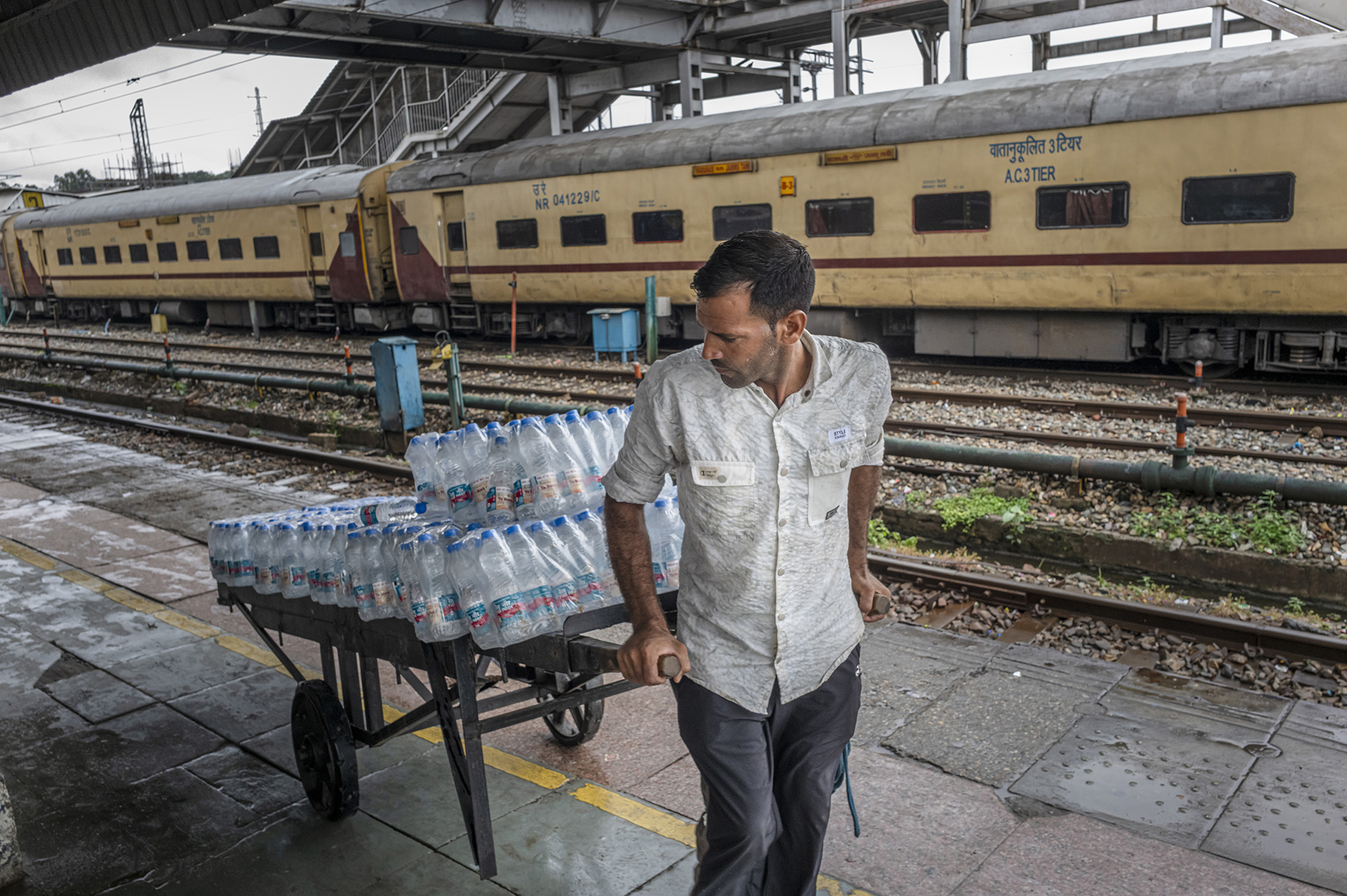

JAMMU, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: Workers at the Jammu central station ensure the supply of water is available during the hot and humid rainy season.

JAMMU, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: Diksha Chaudary (28) says goodbyes to her husband with their child Myvah (2) as the train leaves towards Kashmir from the Jammu central station.

Before the new railway opened there were only two ways to travel to Indian Kashmir. Either by air, too costly for most, or by road which was often impassable in rain and snow. The new train changes all that and aims to provide a weatherproof and affordable connection that can be used all year round. But this isn't its only purpose. The official government line is that there are also economic motives for building the train: improving job opportunities for Kashmiris, strengthening the valley's economy and stimulating tourism from other parts of India. Kashimiris see it in a very different light.

JUDDA, JAMMU & KASHMIR, INDIA: The train to Kashmir is heavily guarded by Indian security personnel, who stand guard between the carriages.

JAMMU, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: Commuters make their way through Jammu central station.

JUDDA, JAMMU & KASHMIR, INDIA: Kashmiri train attendants and conductors staff the train that connects Kashmir to other regions in India.

JAMMU, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: Gurjeet Singh (53) , a luggage attendant, helps to tag a communter's bag at the Jammu railway station. Baggage attendants at the railway station in Jammu work to tag and administer the bags coming through the station every day.

BAKAL, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: A view of the Chenab river, with the Chenab Railway Bridge in the distance - the highest railway bridge in the world.

REASI, JAMMU & KASHMIR, INDIA5: The son, daughter, and niece of Nitul Kakati (42) and Priti Mahanta (38) are sleeping on the train towards Kashmir. They are on a holiday trip and have taken the train for the fables views and have turned their seats to face the window - a specialist feature of the train.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Communters and tourists arrive at the railway station in Srinagar, Kashmir.

Kashmir is India’s only Muslim-majority region. It has its own distinct culture and language. Many residents seek the ability to practice their religion and maintain their cultural traditions. But these freedoms have long been threatened by decades of war and a strong presence of India's security forces. The regions is one of the most militarised aresas in the world. It is estimated that there is one police officer or soldier for every thirty Kashmiris.

SALLAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: The lack of customers drives some to desperation. Further down the valley, a taxi driver lashes out at a colleague, landing a blow to his jaw. A sharp decline in tourism after an April 22nd terrorist attack on a group of tourists, has meant less income for the Kashmiri’s dependent on tourism.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: A view of the old center of Srinagar. Srinagar’s old quarter, is a warren of narrow lanes, centuries-old shrines and bustling bazaars along the Jhelum River. Its two- and three-story houses, built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, bear both Kashmiri detail and traces of European influence.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Locals cross a busy street in Srinagar in India’s Kashmir valley which unlike the rest of India has a predominantly muslim population.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Students in Srinagar from Ladakh enjoy a day of cycling by the lake and eat lotus flower seeds.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Women pray together at the Friday afternoon prayers at the largest mosque of Srinagar: the Dargah Hazrathbal Shrine.

PAHALGAM, KASHMIR, INDIA: A Kashmiri working in Pahalgam earns a living from his horses that take up tourists into the Himalayas - particularly during the yearly Amarnath Yatra, a Hindu pilgrimage to a holy cave housing a sacred ice stalagmite (Shiva Lingam) in the mountains. On April 22nd, a terrorist attack killed 26 tourists in the valley, triggering a sharp decline in tourism in the Kashmir valley.

PAHALGAM, KASHMIR, INDIA: Indian Yatra (the yearly Amarnath Yatra, a Hindu pilgrimage to a holy cave housing a sacred ice stalagmite in the mountains) tourists come to the Pahalgam valley to do their pilgrimage to a holy site in the Kashmiri mountains.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: At Srinagar's Dal Lake - a popular tourist destination - boat driver Mohammed Mukbool (62) sails his boat with tourists over the lake every day. Business is down since the April 22 2025 attack from a militant group killed 26 people in nearby Pahalgam.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: At Srinagar's Dal Lake - a popular tourist destination - a family has travelled to enjoy a day on the lake. On the right, Nitul Kakati (42) and Priti Mahanta (38) with their 4-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: A local fisherman fishes in the large Dal Lake, under watch by Indian military forces. Another local resident enters into a discussion with another soldier on patrol. Riot police and Indian military patrols control the streets in Srinagar with countless checkpoints and patrols throughout the city. The region is one of the most militarized in the world.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Riot police and Indian military patrols control the streets in Srinagar with countless checkpoints and patrols throughout the city. The region is one of the most militarized in the world, with one in thirty residents Indian military or police, patrolling a predominantly muslim society (which forms a minority in India, but a majority in Kashmir for now).

Since the partition of British-ruled India in 1947, the Kashmir valley has stood at the center of one of the world’s most enduring conflicts between India and Pakistan. Some Kashmiris long for unity with Pakistan, while others have continued to push for independence. Protests in 2019, when India stripped the region from its semi-autonomous status, were crushed violently: the internet was shut down, movement was restricted, and many dissenting voices were either jailed or silenced.

In April of 2025, armed militants attacked a group of Indian tourists in Pahalgam, which led to a resurgence of violence between the two nuclear powers. India and Pakistan traded missile strikes and drone attacks in the region that killed scores of civilians on both sides of the line of control. In the aftermath, India reinforced its troop deployments in the Kashmir valley and tightened security measures even further, extending checkpoints, patrols, and restrictions on movement.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Police and Indian military patrols control the streets in Srinagar with countless checkpoints and patrols throughout the city. The region is the most militarized in the world, with one in thirty residents being Indian military controlling a predominantly muslim society.

PAMPORE, KASHMIR, INDIA: In Pampore, near Srinagar, Sarah Begum (68) and her grandson Amar (5) sit by a window in their house.

BAKAL, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA5: Buburam (50) ascends the mountain surrounding the valley in which he lives with his family, together with his livestock, for them to graze. Buburam worked on the construction of the Chenab Rail bridge. They say officials promised his family - and they hoped for - a station in the valley, so they could sell artifacts and food to travellers, but this was never realized.

BAKAL, JAMMU & KASMIR, INDIA: In the mountains between Jammu and Kashmir, children at a local middle school play cricket. Cricket is a deeply shared cultural passion and a significant sport for both Indian, Kashmiri and Pakistani people, originating from British colonial rule.

PAHALGAM, KASHMIR, INDIA: Kashmiri girls walk home from school in the Pahalgam valley.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Local Kashmiris in Srinagar doing their grocery shopping at a local marketplace by a mosque in the old center of the city.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: A car passes through a checkpoint at the outskirts of Srinagar. Police and Indian military patrols control the streets in Srinagar with countless checkpoints and patrols throughout the city. The region is the most militarized in the world, with one in thirty residents being Indian military controlling a predominantly muslim society.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Riot police and Indian military patrols control the streets in Srinagar. The Indian military presence is large in Kashmir. It is one of the most militarized regions in the world with one out of thirty residents are military or police. The military presence is mostly non-muslim Indian, whereas the local inhabitants of Kashmir are predominantly muslim.

SRINAGAR, KASHMIR, INDIA: Throughout Kashmir - one of the most militarized region in the world - military bases lie scattered throughout the region.