Mads has been documenting the civil war in Colombia since 2010.

More than 50 years of conflict between the government army, guerrilla rebels and paramilitary groups have led to the the death of over 200,000 people and the internal displacement of 7 million citizens, leaving visible scars on the landscape and people of Colombia.

Colombia is the world's biggest producer of cocaine, fuelled by demand from the US and Europe.

The economics of this drug trade, intertwined with poverty and inequality, in a country with an ingrained history and culture of violence, has fed the cycle of unrest over the decades.

Astri Gisela Yunda Lopez (7) and Feryi Geraldin Yunda Lopez (9) stand in a field surrounded by their father's cannabis plants. Cultivating marijuana risks bringing armed conflict and drug abuse to the local community but, as their father Jesus Antonio Yunda explains, without the income from these illegal crops he is unable to pay for the girls' school uniforms and to put food on the table.

A group of youths harvesting coca leaves stand with the sacks they are filling. From left: Yorley Munoz Munoz (16), Sebastian Moreno Moreno (21), Adan Alberto Hernandez Moreno (15), Ariel Albeiro Munoz Munoz (19) and Fray Munoz Areiza (16). The coca picking starts at 5am in the morning, and during a working day a person usually collects two sacks of leaves weighing approximately 70 kilos each. For this they'll be paid 24,000 Pesos (GBP 6.15), about twice as much as they would receive harvesting coffee.

Mads' work shows the main actors in the conflict as well as ordinary citizens whose daily lives are caught in the middle of violence.

The civil war, the longest running in recent history, grew out of partisan conflicts in the 1920s.

By the 1960s it had escalated into an inextricably complex civil war pitting the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) against the Colombian Army and paramilitary groups often linked to drug cartels and domineering land owners.

For decades, thousands of highly motivated guerrilla fighters - many of them women - hid in jungle camps in Colombia's inaccessible interior.

When not engaged in bouts of fighting with government forces and right wing paramilitary groups FARC rebels raised money by taxing and controlling parts of the illegal drug trade.

President Juan Manuel Santos, elected in 2010, started secret negotiations with the FARC.

This led to an agreement that was eventually approved by both houses of parliament, despite much political opposition and an initial No vote in a referendum on the terms of the first version of the agreement.

While the agreement has been signed by all relevant parties, however, the implementation is fraught with difficulties and will take many years.

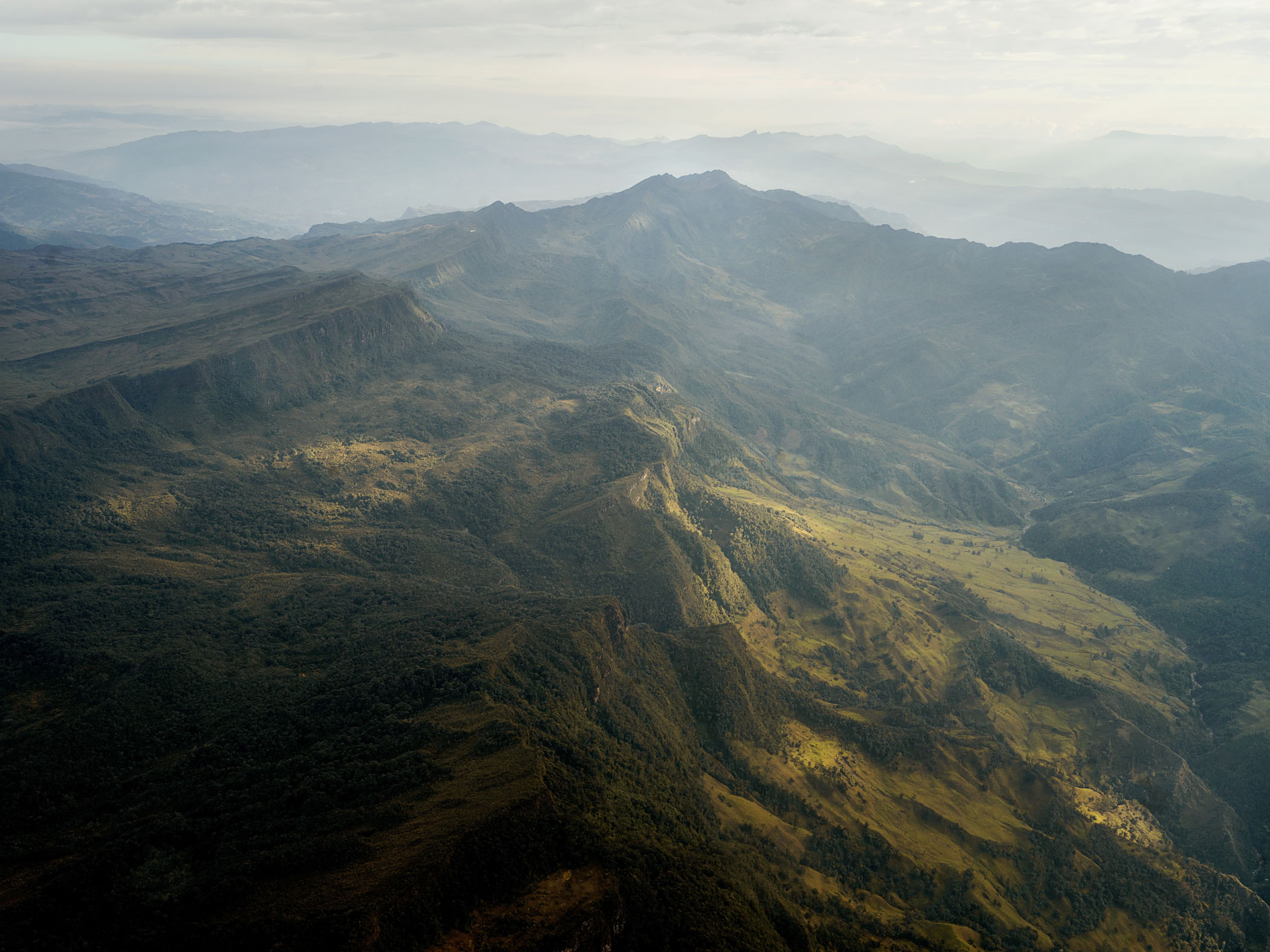

With the conflict winding down in rural and remote parts of the country, scientists have started to gain access to formerly no-go areas where they are discovering new plant species

Illustrations by Lisa Anzellini

"I landed in Aeropuerto El Dorado in mid October 2016 and stepped foot on shaky ground.

In civil war the front lines are always intertwined; a Gordian knot in chains. But after fifty-two years of fighting in Colombia, they were suddenly unravelling. Anything could happen.

The peace agreement, meant to have ended the longest running civil conflict in the world, had unexpectedly been felled in a plebiscite a few weeks prior to my arrival in the country. For four years, the Colombian government had negotiated fiercely with one of the world’s largest and most tenacious guerrilla movements, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), prominent on Western terror lists.

According to the agreement, the FARC were to give up their military functions and relinquish control of all the land they had taken. More than seven thousand seasoned guerrilla soldiers were to hand over their weapons and phase back into civilian life with personal finances, households and ordinary jobs; a scary thought for the many soldiers who had fought in the ranks since they were teenagers.

In return, the FARC were to be spared long prison sentences, removed from the terror lists and would be able to run as a political party for ten earmarked seats in Congress at the next two elections.

The agreement also contained a series of political breakthroughs such as a comprehensive system for truth, justice and reparation, as well as an extensive rural reform which, among other things,

provided more rights to the millions of Colombians who had been robbed and driven off their farmland. They should now be able to return home and reclaim their lands without fear of reprisals, chicanery and murder.

Another focal point of the agreement was the country's cocaine production.

Cocaine had been key to financing the armed groups of the conflict. Impoverished coca farmers were to receive government subsidies to grow legal crops and no longer be under military attack. Was a time of optimism in Colombia.

Nonetheless, the long suffering Colombian population rejected the agreement. So, what happened? Were the political demands unacceptable to the elite? Or were the feelings of hatred too recent and raw and all the trust in tatters?

The body of Gerson Acosta is carried to a grave. The murders of local civil society leaders pose a serious risk to the peace process in Colombia. Governor, prominent Indigenous leader and member of Consejo Regional Indigena del Cauca (CRIC), Gerson Acosta, 35, was the 31st leader to be killed since the implementation of the peace accords in December 2016. His community in Kite Kiwe suspects a right-wing paramilitary group to be behind the assassination.

The coffin of Gerson Acosta, draped in the colours of the Consejo Regional Indigena del Cauca, the indigenous group he led, and mourners at his funeral.

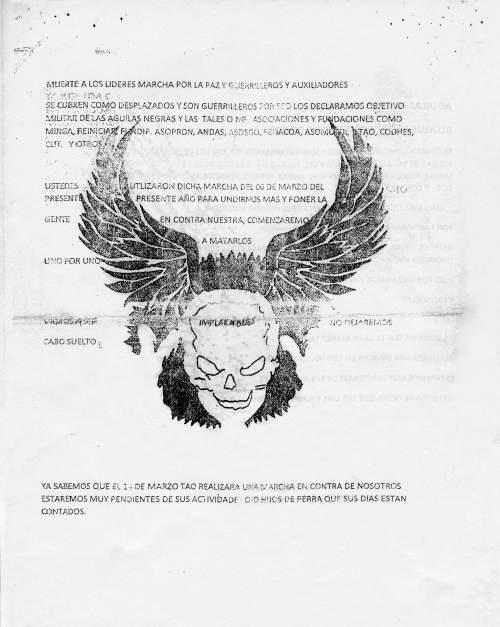

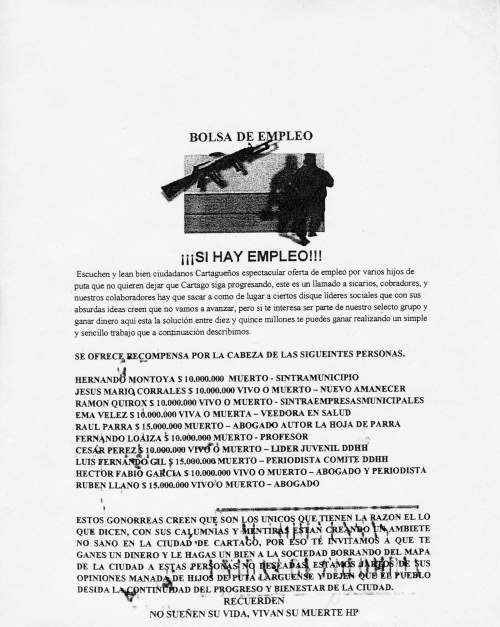

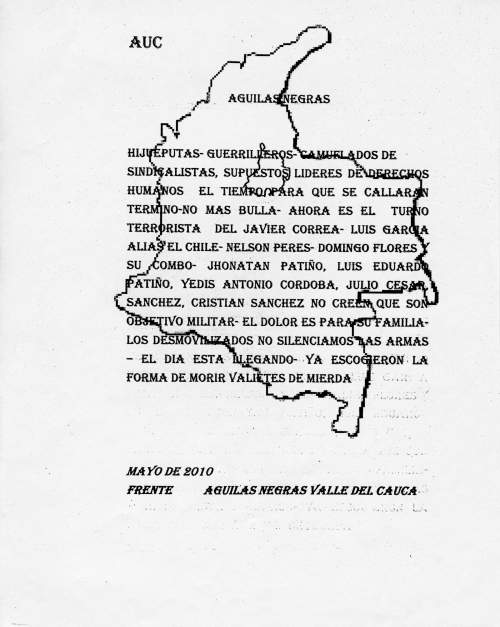

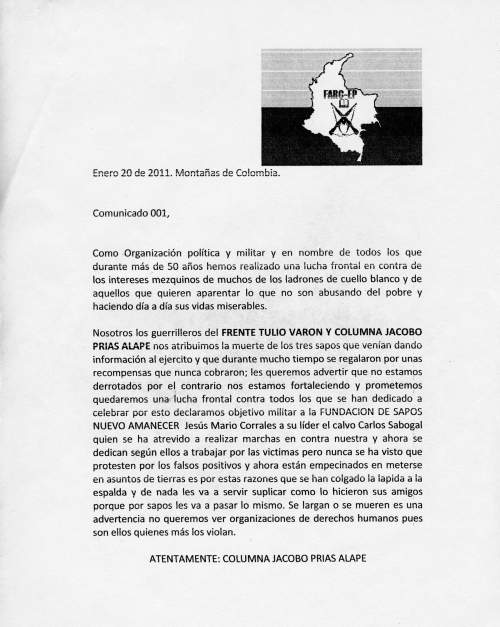

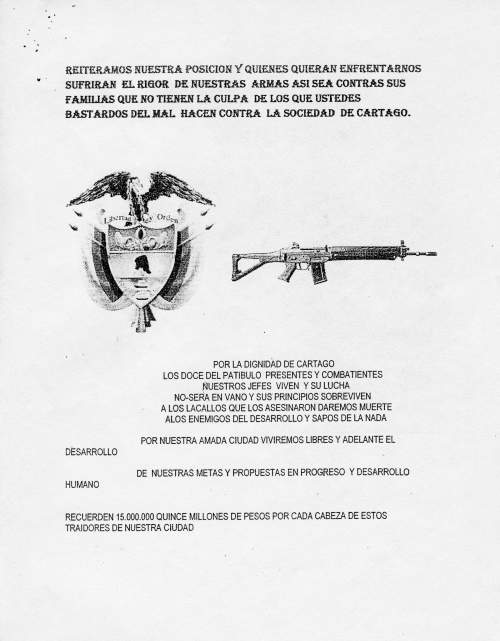

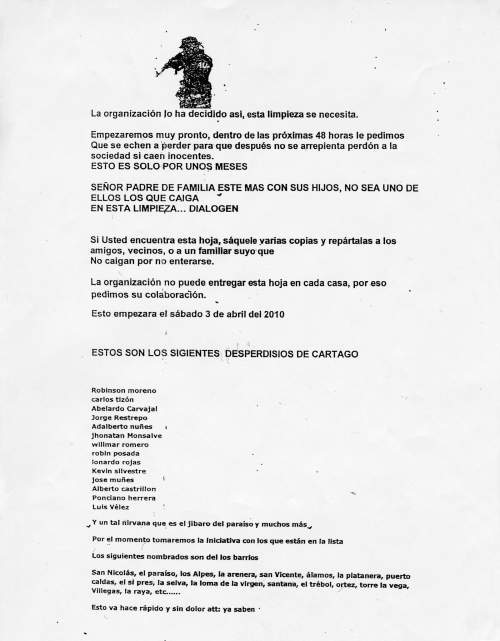

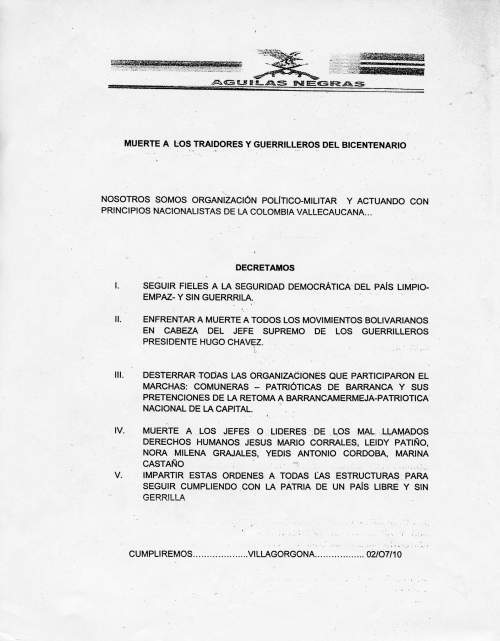

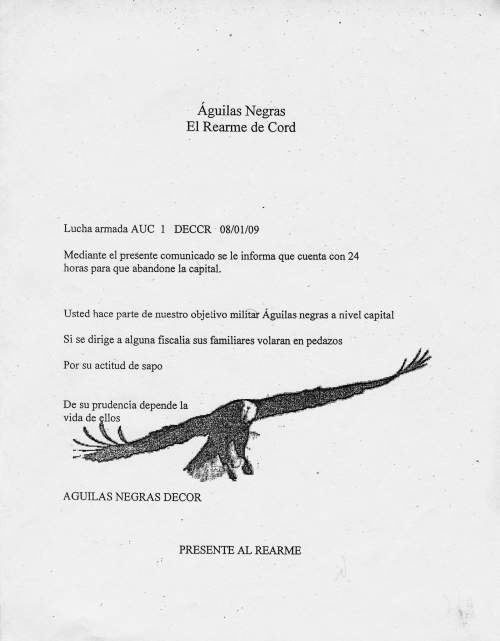

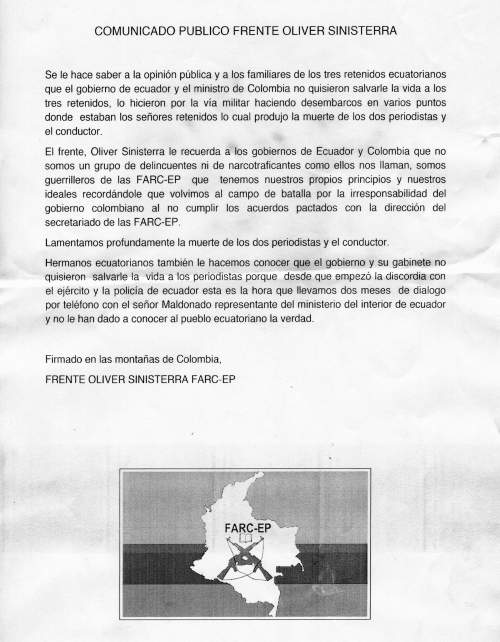

Propaganda leaflets distributed to communities and individuals in regions of rebel activity.

Reconciliation was no easy task: 220,000 people had been killed during the conflict and few countries have a history as steeped in violence as Colombia.

The violence runs from the war of independence in the early 19th century through La Violancia, a bitter struggle between the Conservative and Liberal Parties marked by massacres and torture which claimed the lives of 300,000 people in the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1964, a group of farmers who had survived a government massacre decided to found the FARC, a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla. Their declared aim was to topple the government and bring freedom to the people.

But freedom was a long time coming and as the decades and battles passed by, more and more armed groups joined the fray until 1970, when a new player joined the fray: the Medellin and Cali drug cartels.

Using ruthless brutality and political alliances, especially to ring wing militia groups, the drug cartels quickly changed the dynamic of the conflict.

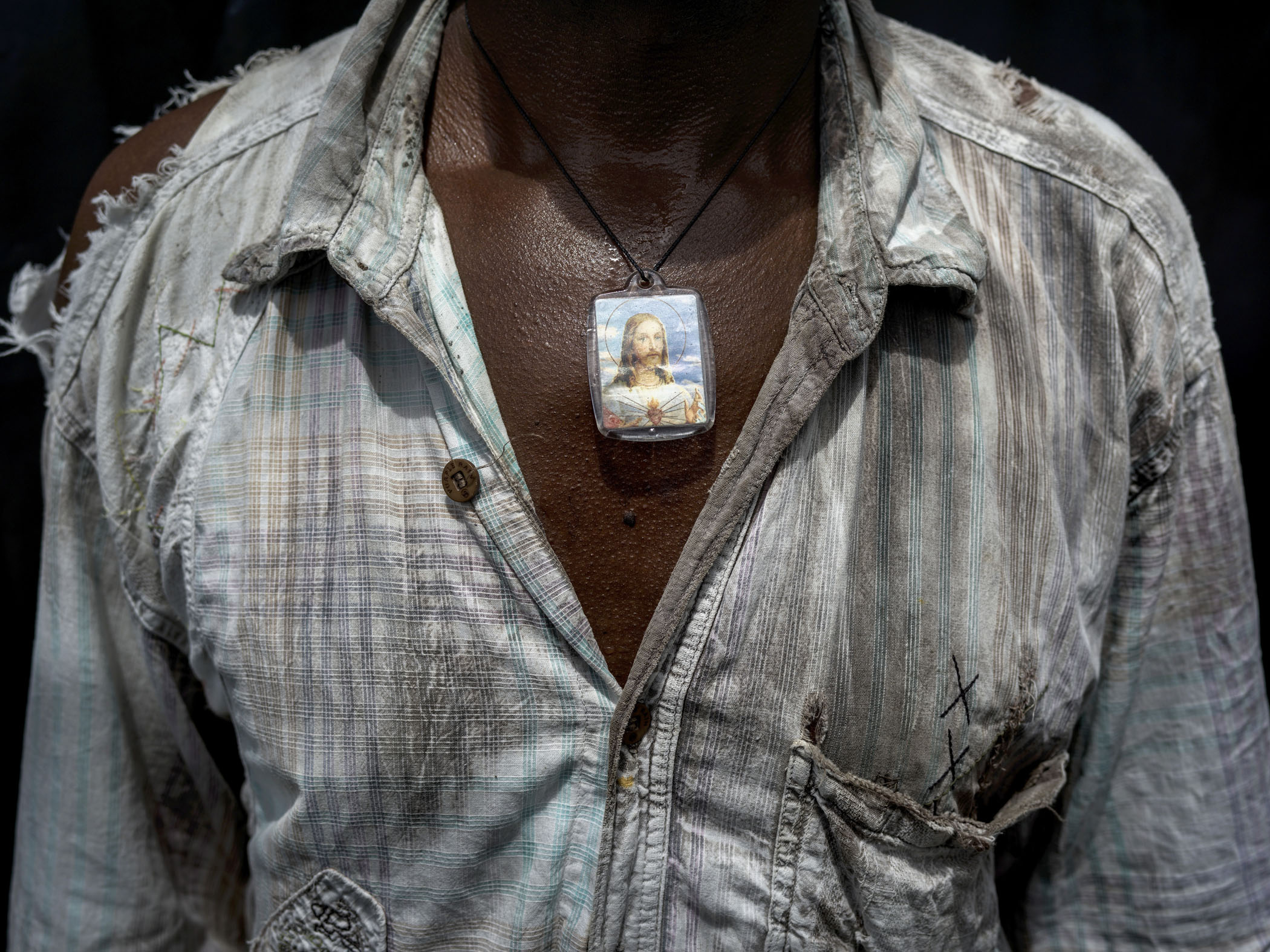

The situation festered, especially in the countryside, where farmers were caught between changing victors who each demanded complete loyalty.

In the middle of the 1980s, the FARC took a stab at parliamentarism and created the left-wing Union Patriotic party. But before long, the slaughter started and thousands of party members and candidates were murdered.

The FARC continued the armed struggle and in the 2000s had an army that numbered around 20,000 soldiers and controlled up to one third of the country.

As so often in Colombia, violence was fought with even more violence.

New right-wing armed groups such as the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) and the Aguilas Negras (Black Eagles) appeared on the scene with modern weaponry and solid support from large parts of the political establishment, tasked with carrying out the dirty work.

The warn burned ever hotter, leaving seven million desplazados (displaced) in its wake who gathered in urban slums such as Soacha and Ciudad Bolivar in Bogota and Puente Nayero in the coastal city of Buenaventura.

With American military and financial support, the government launched campaigns both against drug producers and the FARC, often conflating the two, throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

Abuses occurred on both sides of the frontline.

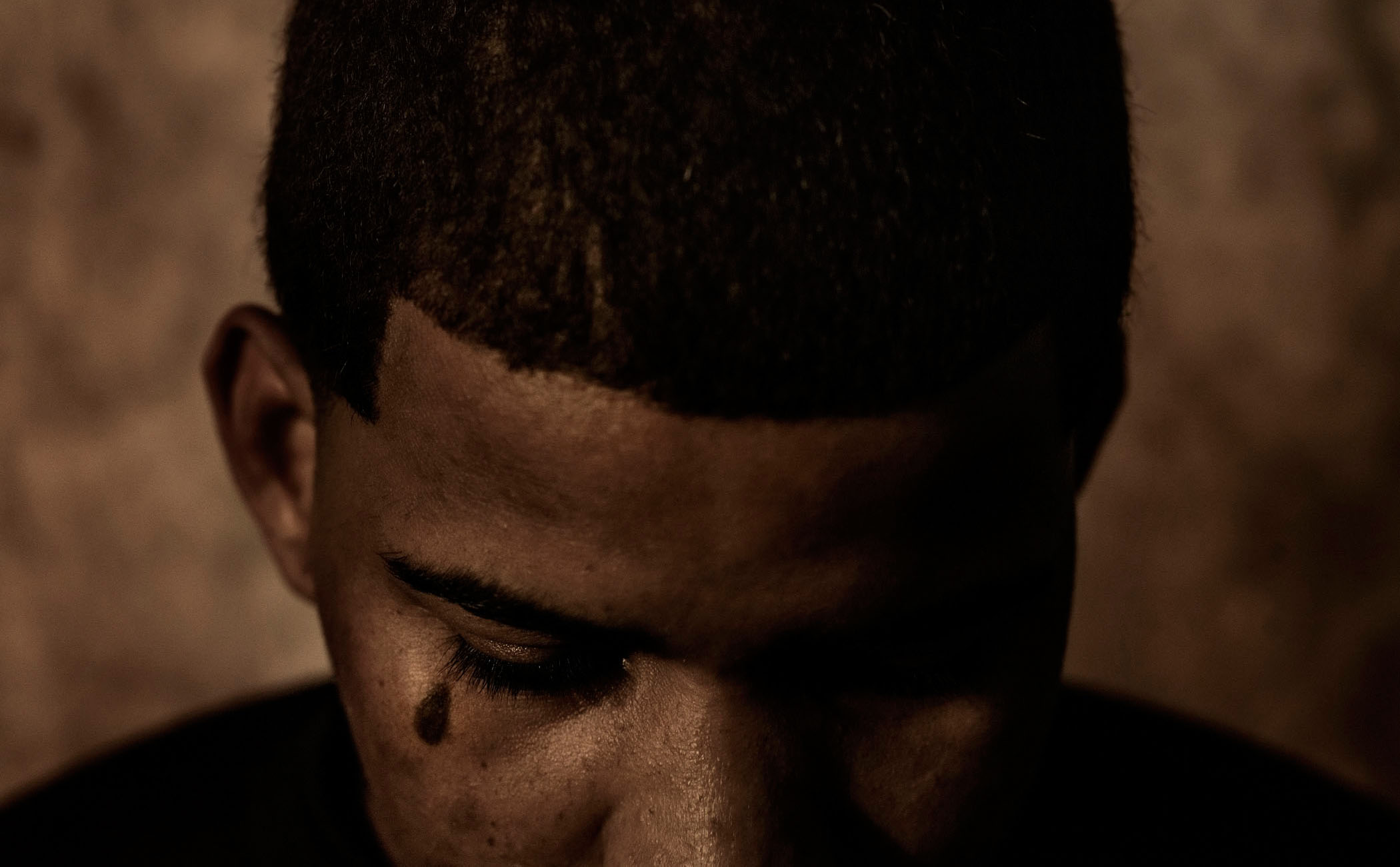

The FARC recruited minors, kidnapped civilians and maintained a harsh rule in the areas they controlled. The Army, on the other hand, murdered thousands of civilians in what were known as ‘false positives’ campaigns. During these, primarily young men from poor neighbourhoods were kidnapped and executed whereupon soldiers staged scenes of combat with weapons and fake guerrilla uniforms in order to claim victories and get promotions.

The Minister of Defence at the time was Juan Manuel Santos.

As the FARC leaders and guerrillas were felled, one by one, his popularity rose and in 2010 he was elected president on the strength of his promise to bring the weakened rebels to the negotiating table and sign and enduring peace.

President Juan Manuel Santos in his office at the Palacio de Narino, the official home and principal workplace of the President of Colombia. October 2016

The former leader of the FARC Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, known by his noms de guerre Timoleón Jiménez or Timochenko, studies newspapers with his girlfriend Johanna Castro and dog Winny. He ran for the presidency at the head of the newly formed Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Comun in 2018 but had to drop out of the race due to a heart attack.

The agreement became a reality and was signed by President Santos and the Timoshenko, the then FARC Commander-in-Chief. Symbolically clad in white for the occasion, the former mortal enemies shook hands with the world as their witness. Finally, peace had come to Colombia – or so most thought – until the plebiscite shortly thereafter, when it all fell apart again.

A few days later, President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize nonetheless for his efforts and as an endorsement for the next round of peace talks.

It was in these weeks of complete turmoil that the work of this book began.

It took another three months to iron out further disagreements between the parties to the agreement for a final deal could be signed in November 2016.

As agreed, the FARC soon moved from their secret jungle outposts into camps monitored by the United Nations. A total of 17 shipping containers of weapons and ammunition were discretely destroyed and what had been the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia became the Fuerze Alternativa Revolutionaria del Comun, or FARC.

President Santos once declared that "making war is easy, making peace is much more difficult". And so it seems.

In many previously FARC controlled areas, other armed groups are now moving in and a growing number of FARC dissidents are rearming and returning to their former way of life.

Since the adoption of the peace process, both previous FARC members and almost 300 social leaders and human rights activists have been murdered while millions of internally displaced have yet to get the land back that was taken from them.

Social problems persist – Colombia ranks among the 10 least equal societies in the world – and two thirds of farm land is controlled by just 0.4% of farmland holdings.

And the coca and marijuana plantations continue to flourish on the hillsides as never before..."