Since the discovery of the first South African diamond in 1867, the country's mining industry has generated extraordinary wealth for outsiders and elites, yet few of the benefits have trickled down to local communities in mining areas, which remain among the most marginalised in the country. Now the industry is in decline, leaving in its wake environmental destruction, more than 6,000 abandoned mines, and a vast population of disenfranchised young men who will do anything to support their families. In response, growing numbers are entering the brutal world of illegal mining to make ends meet, and to reclaim resources they feel have for too long been looted by outsiders. Locally, they are known as Zama Zamas - "those who take a chance".

An aerial view of the village of Duvha, which lies next to a coalmine and the coal fired Duvha power station, in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Mpumalanga, the heartland of the country's coal industry, has some of the worst rates of air pollution in the world according to a 2018 analysis of satellite data.

Illegal coal miners haul a wheelbarrow full of coal, weighing some 125kg, up a dirt track from an informal mine outside Ermelo, South Africa. The activity is considered illegal by police because the miners do not have a license, yet the town depends on their coal, and the economy surrounding it.

Illegal miners descend into the abandoned Golfview coal mine in Ermelo, South Africa. There are over 6,000 abandoned mines across South Africa. Amid widespread poverty and high rates of unemployment, these are now increasingly being taken over by so-called Zama Zamas, illegal miners willing to undertake great risks and hardships to support their families.

Artisanal miner Emmanuel Siyabonga slumps against a wall while suffering from fatigue and a severe headache after hauling a sack of coal out of the abandoned Golfview coal mine in Ermelo, South Africa. The arduous nature of the work, and particularly exposure to toxic gas underground, have had a severe impact on the Siyabonga and his colleagues. Two days after this photo was taken, the bodies of two miners were found by police here. They are presumed to have been killed by dangerous gases underground.

While mining companies routinely fail in their legal obligations toward local communities and the environment, it is the Zama-Zamas who find themselves targeted by the authorities, at times with extreme violence. As a result, they are forced to operate in the shadows, working in brutal, dangerous conditions without safeguards or support, for just a few dollars a day.

This project, shot over several years, explores the murky world of these outlaw miners who undertake extraordinary risks and extreme hardships, all the while being hounded by police. It looks at the deadly work of illegal coal mining in Mpumalanga province, illegal diamond mining in the deserts of Namaqualand, a deadly rush for chrome in North West Province, and a police siege in the town of Stilfontein that left over 90 illegal gold miners dead.

Themba Zimila, 27, photographed with his family at his home in the informal settlement of MNS in the coal mining town of eMalahleni, South Africa. The family lives next to a large colliery yet lacks electricity and other basic services. The main is looking to expand and is seeking to have the family relocated.

Derelict mining infrastrure is seen in a flooded section of the abandoned Golfview coal mine outside the town of Ermelo, South Africa. The mine declared bankruptcy in 2009 and never met its obligations to rehabilitate the area. It is now mined illegally by artisanal miners who undertake great risks to extract leftover coal.

Artisanal coal miners prepare to deliver a wheelbarrowful of coal to buyers at the abandoned Golfview mine in Ermelo, South Africa. Much of the local community relies on the coal produced by illegal mining at sites like this one.

Artisanal miners at work inside the abandoned Golfview coal mine in Ermelo, South Africa. The work is gruelling and hazardous, particularly in recent months after sections of the mine became filled with poisonous gas. But amid widespread unemployment, many say this is the only way they can continue to feed their families.

An artisanal miner displays a handful of coal at an illegal mining site in Ermelo, South Africa. Coal generates nearly 80% of South Africa's electricity, but it is also used by millions for cooking and heating, particularly in areas that still do not receive mains electricity. Much of this demand is met by artisanal miners, who go underground and work in tough conditions at considerable personal risk.

An aerial view of homes in the informal settlement of Enkanini, in Ermelo, South Africa. Enkanini, which loosely translates as "the place of the strong willed", lies on the site of an abandoned coal mine. The community is currently engaged in a class action lawsuit over the mining comnpany's failure to adeuqately rehabilitate the land after stopping operations.

Albert Mkalat, an illegal coal miner originally from Mozambique, photographed outside an informal mine outside Ermelo, South Africa.

A waste dump at a coalmine looms over shacks in the township of Vosman in eMalahleni, South Africa. Residents of Vosman complain of numerous issues caused by the coalmine, from noise, dust and air pollution to disruption caused by reglar controlled blasts. For over a century, mining in South Africa has consistently failed to significantly improve the quality of life of local communities.

An illicit coal miner, known locally as zama zamas, walks through a landscape scarred by large scale mining at the abandoned Golfview mine in Ermelo, South Africa. Mining companies are required by law to rehabilitate their land after ceasing operations, yet in practice this rarely happens. Illegal coal mining, often on abandoned industrial mines, is rampant throughout Mpumalanga province, providing a livelihood, albeit an arduous and dangerous one, to thousands of unemployed men and women.

Coal is burned in the front yard of a home next to a large coal mine in eMalahleni, South Africa. Coal is used to generate most of South Africa's electricity needs, but many poor communities in the country's coal heartland still lack access to mains electricity. As a result, they are heavily reliant on coal for cooking and heating among other things.

Artisanal coal miners shovel coal onto a truck at Ding Dong mine outside Ermelo, South Africa.

A man is carried by paramedics to a waiting ambulance after being rescued from a disused mineshaft in Stilfontein, South Africa. A police operation to combat illegal mining aimed to force zama zamas to the surface to face arrest, but resulted in dozens starving to death underground.

A shaft at the abandoned Stilfontein Gold Mine in Stilfontein, South Africa. After the mine closed down, laying of thousands of workers, its remaining gold reserves became a magnet for unemployed young men from across the southern Africa region. In January 2024, a police operation designed to force illegal gold miners to resurface and face arrest led to the death by starvation of at least 87 people at the mine.

Zinzi Tom, 31, whose brother was among hundreds of zama zamas trapped underground for months during a police operation against ilegal mining, displays footage from the mine showing dozens of bodies wrapped in makeshift bodybags, as the government's rescue operation belatedly gets underway in Stilfontein, South Africa. Rescue efforts by the community and later the government extracted hundreds of living miners as well as 87 bodies. Tom's brother remains unaccounted for.

Minister of Mineral Resources, Gwede mantashe (centre) and Police Minister Senzo Mchunu (in checked shirt), laugh with their entourage as they visit the site of a rescue operation at a disused gold mine in Stilfontein, South Africa, where illegal miners had been trapped underground for months amid a police crackdown.

Zama zamas process gold in a backyard in Khuma, South Africa, where illegal gold mining is a major source of employment. This part of the township, known as Extension 6, is believed be under the control of a powerful Zama Zama cartel from Lesotho. It is home to many of those who became trapped by operation Vala Umgodi in Stilfontein.

A zama zama inspects a lump of gold and mercury amalgam in an illegal backyard gold operation in the township of Khuma near Stilfontein, South Africa. The amalgam will later be heated to evaporate the mercury.

Mametlwe Sebei of the legal non-profit, Lawyers for Human Rights addresses reporters during a government operation to rescue miners trapped underground at an abandoned gold mine in Stilfontein, South Africa. The miners were left stranded after a police operation cut off their supply of food, water and medicine. At least 87 bodies have so far been recovered from the mineshaft.

Patrick, an ilegal gold miner who spent months trapped underground in a mineshaft during Operation Vala Umgodi, embraces his mother at his home in the township of Khuma in Stilfontein, South Africa. Patrick escaped by undertaking a perilous climb up a nearby connected mineshaft, a journey that took him five days. He was then arrested by police and is currently out on bail awaiting trial.

The site of an abandoned mine shaft at the former Stilfontein Gold Mine in Stilfontein, South Africa. After the mine closed down, laying of thousands of workers, its remaining gold reserves became a magnet for unemployed young men from across the southern Africa region. In January 2024, a police operation designed to force illegal gold miners to resurface and face arrest led to the death by starvation of at least 87 people at the mine.

Zama zamas drink at a bar in the Section 6 area of Khuma, near Stilfontein, South Africa. The area has high rates of unemployemnt and is home to many illegal gold miners.

A zama zama dances with a woman in abar in the Section 6 area of Khuma near Stilfontein, South Africa. Illegal gold mining is one of the few available sources of income for many in the community.

Jefferson Ncube, an informal diamond miner from Zimbabwe, works on his latest tunnel at a disused De Beers mine near Kleinzee, South Africa. The work is considered illegal by the government, and is completely unregulated. Accidents are common, with miners regularly losing their lives when tunnels collapse. But in region with few other economic opportunities, the mines are a major draw for unemploeyed people from all over southern Africa. Jefferson is a univeristy graduate, but has been unable to find employment.

Laundry belonging to illegal diamond miners hangs on a fence at a diamond mine in Namaqualand, South Africa.

Artisanal diamond miner Kim Cupito, photographed in her home, a derelict building left behind by De Beers at the Nuttabooi mine near Kleinzee, South Africa. The mine is now occupied by hundreds of artisanal miners deemed 'illegal' by the government. Cupito, however, does not recognise the government's claim to the area's mineral wealth. "This is God's ground" she says. "It's for everybody".

Artisanal diamond miners sort through gravel with a jig at an illegal dig site in Namaqualand, South Africa. The mine was formerly operated by DeBeers, who extracted and exported vast quantities of diamonds over several decades. Despite the extraordinary wealth extracted from its soil, the Namaqualand region remains plagued by extreme poverty, poor service delivery and chronic joblessness, all of which fuel illegal mining in the area.

Mishek Mugwire, 38, a former baker from Pretoria, climbs up a vertical mine shaft without ropes at an illegal diamond mine outside Kleinzee, South Africa. The work is hazardous in the extreme with tunnel collapses and cave-ins frequent, but Mugwire says he has little choice but to keep going in order to support his family. He prefers not to dwell on the risks of the job. "When you die, you die" he says.

Illegal diamond miners sift through sand at gravel at an abandoned mining site outside Kleinzee, South Africa.

Zimbabwean migrant diamond miners sift through gravel and rocks in a makeshift bar in a squatter camp at an abdoned diamond mine in Namaqualand, South Africa. Over the past few years, many Zimbabweans have turned to the dangerous but lucrative work of illegal mining in South Africa, driven by widespread unemployment, inflation and poverty in their home country.

An illegal diamond miner from Lesotho stands outside his makeshift shelter in a mining camp in the desert near Kleinzee, South Africa. The area has been the scene of widespread illegal mining since De Beers pulled out a decade ago.

Mishek Mugwire, 38, a former baker from Pretoria, hacks away at the sandy soil with a piece of sharpened rebar in a newly dug tunnel at an illegal diamond mine near Kleinzee, South Africa.

An illegal diamond miner checks his phone on top of a pile of gravel in a mining camp at the site of an abandoned De Beers mine near Kleinzee, South Africa. Before a series of recent police raids, the camp was home to thousands of people from across the region.

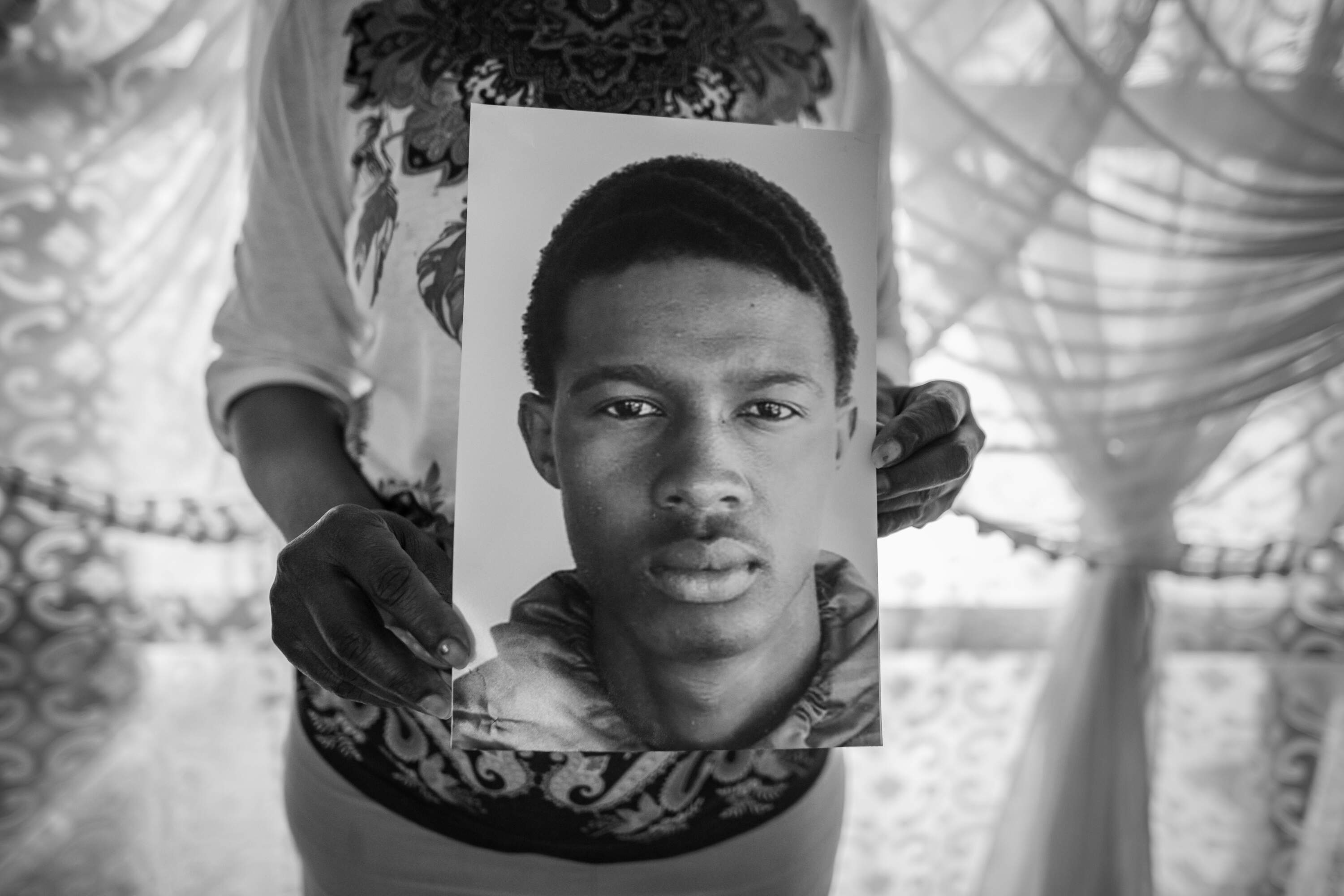

Margaret Ditshwana holds a photo of her son, Thabang, who died at the age of 30 in an accident at an illegal chrome mine in Witrandjie, South Africa. Thabang and another man were killed by falling debris while collecting chrome in March 2023.

Chrome pickers search for chrome-bearing rocks on top of a towering waste dump outside Witrandjie, South Africa. Illegal mining accounts for as much as 10% of all South Africa's chrome exports.

A chrome miner walks along the dirt road to the village of Witrandjie, South Africa, which is surrounded by dozens of unlicensed chrome mines.

36-year-old Godfrey Molwana pictured near his home in the village of Witrandjie, South Africa. Molwana says the quality of life in the village has been drastically reduced since the onset of massive scale illegal chrome mining, turning bucolic grazing lands into a mine-scarred wasteland and sowing divisions and violence in a community that was once peaceful and united.

A derelict building stands at the top of a set of steps leading to a section of the former Golfview coal mine in Ermelo, South Africa. At times, hundreds of artisanal miners worked illegally inside the old mine, many driven by poverty and the lack of alternative job opportunities.