Countless former day labourers who worked on building sites across Japan in the 70s and 80s find themselves trapped in an economic void, too old to work and too young to claim benefits.

Kamagasaki, a neighbourhood of Osaka, used to be the biggest day labourer town in Japan. Today, it is home to about 25,000 mostly elderly former workers, some 1,300 of whom are homeless. Alcoholism, street death, suicide, TB and loneliness prevail. Without family ties, they live and die alone as social outcasts from the mainstream “salary man” culture. With unemployment rising, even among the young and educated, it is a hopeless situation for the graying men who helped build modern Japan.

“There’s no work now. If big companies like Toyota are firing people, why should there be any work here for us? If big banks in the U.S. collapse, why should there be any work here for us?” says Hiroshi Nakao, 59, a former construction worker who currently survives by picking through garbage and selling what he can. He is one of the thousands of graying men in Kamagasaki who have been washed up by the rapidly changing labour market and the stagnating economic fortunes of the country.

Kamagasaki used to be called a “labourer’s town”. Today it is known as a “welfare town” – a dumping ground for old men. Labour towns like Kamagasaki are on the verge of extinction in Japan. According to a recent government report, Japan’s economy, the world’s third largest, is in its worst state since the oil crisis of the 1970s. Youth unemployment and lay-offs at big corporations like Toyota, Nissan, Canon, Sharp, Panasonic, NEC, Hitachi, and TDK are rising sharply.

“I’m mentally prepared that I will never get another job for the rest of my life, but I really want to work.”

64 year old former carpenter who sleeps in a park

The graying men of the construction industry, former labourers who flocked to the big cities during Japan’s long building boom, are at the bottom of the pile. “I’m mentally prepared that I will never get another job for the rest of my life, but I really want to work.” says a 64 year old former carpenter who sleeps in a park.

The average age of the workers here is 58, below 65, the official age when people become eligible for government assistance. “They are stuck in the middle. They are too old for this work but too young to get government assistance. No work, nowhere to go, and nobody to rely on. Some guys just kill themselves. I understand the feeling.” says Yasuo Miyake, 65, a former construction worker who is now living on government assistance.

There used to be plenty of work for construction workers, carpenters and other tradesmen who could earn a little extra through doing odd jobs. Now, because of the recession and their age, there is hardly any work, save the odd government sponsored job mopping the floors at the job center where they once looked for decent paying jobs.

An elderly, unemplyed man in Kamagaski.

79 year old Kenji Yamaguchi, who survives by collecting cans and cardboard boxes.

An unemployed ex-convict who now volunteers at a soup kitchen.

64 year old Satoshi, who used to work for a cabaret.

An unemployed man who is addicted to drugs stands in the rain in Kamagasaki.

64 year old Syunsuke Fujii, an unemployed carpenter.

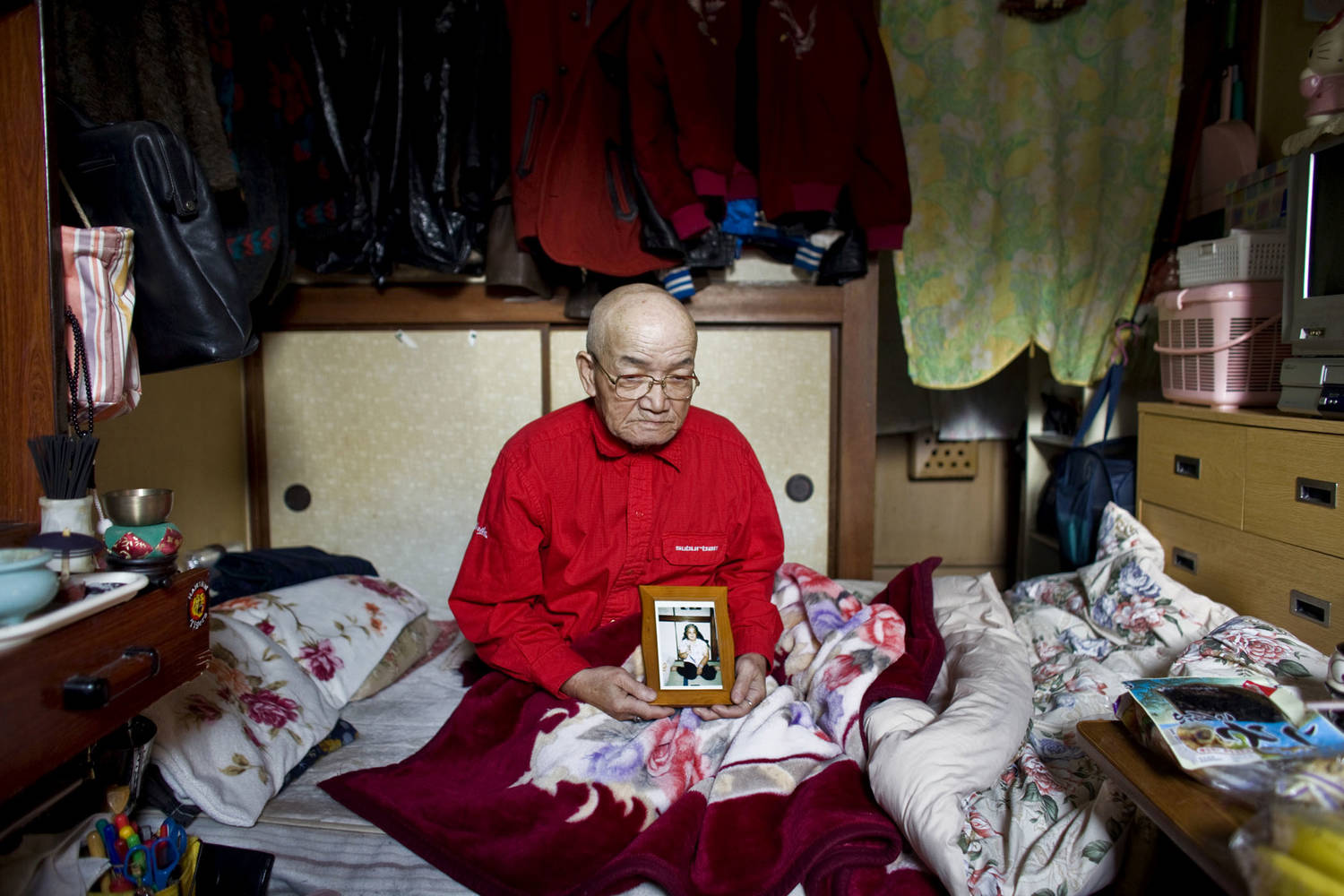

65 year old Tamiichi Kuwata depends on welfare to live.

65 year old Tamiichi Kuwata depends on welfare to live.

“Everyday is a matter of life and death. When it gets cold, I see somebody frozen to death almost every day. They drink cheap sake and lay down and die. The only comfort I have is that I’m not going to starve to death because of charity.”

Toshio Fukushima, 73

A bathroom in a park in Kamagasaki which many homeless people use.

A man drinks at a makeshift bar in Kamagasaki.

A rubbish bin with a smiley face drawn on it at a laundrette in Kamagasaki.

A picture of Mt. Fuji hangs on a fence beneath a highway in Kamagasaki.

A pair of slippers t the bottom of the stairs at a cheap motel for former day labourers.

A sumo wrestler shown on a communal television screen in a in Kamagasaki park where many homeless people sleep.