Across post-communist Eastern Europe, a number neo-nazi and right-wing extremist groups have sprung up in the past 25 years which variously rage against their governments, immigrants, liberalism or the loss of national identity.

In each country where these movements have gained traction the reasons and historical background differ, furnishing each group with different focal points and scapegoats. Many draw on the imagery and philosophy or Europe’s archetypal fascist state – Nazi Germany – or their country’s war-time governments that collaborated with the Nazis.

A relatively new element that is common across many of the groups is the condemnation of Islam and the rejection of Muslim immigrants and refugees which have been coming to Europe in ever larger numbers over the past years, driven by war and instability across the Middle East.

Hungary

Hungary’s right-wing parties such as Jobbik, the 64 Counties Youth Movement or a new outfit – Force and Determination – bemoan the Kingdom of Hungary’s loss of over two thirds of its territory after the First World War and see the large Roma minority as a threat to national identity. With over 20% of the vote in the 2014 parliamentary elections, Jobbik is the third biggest party in the country’s legislature. It campaigns against globalisation, wants to take Hungary out of the EU and perceives ‘Zionist’ meddling in domestic politics.

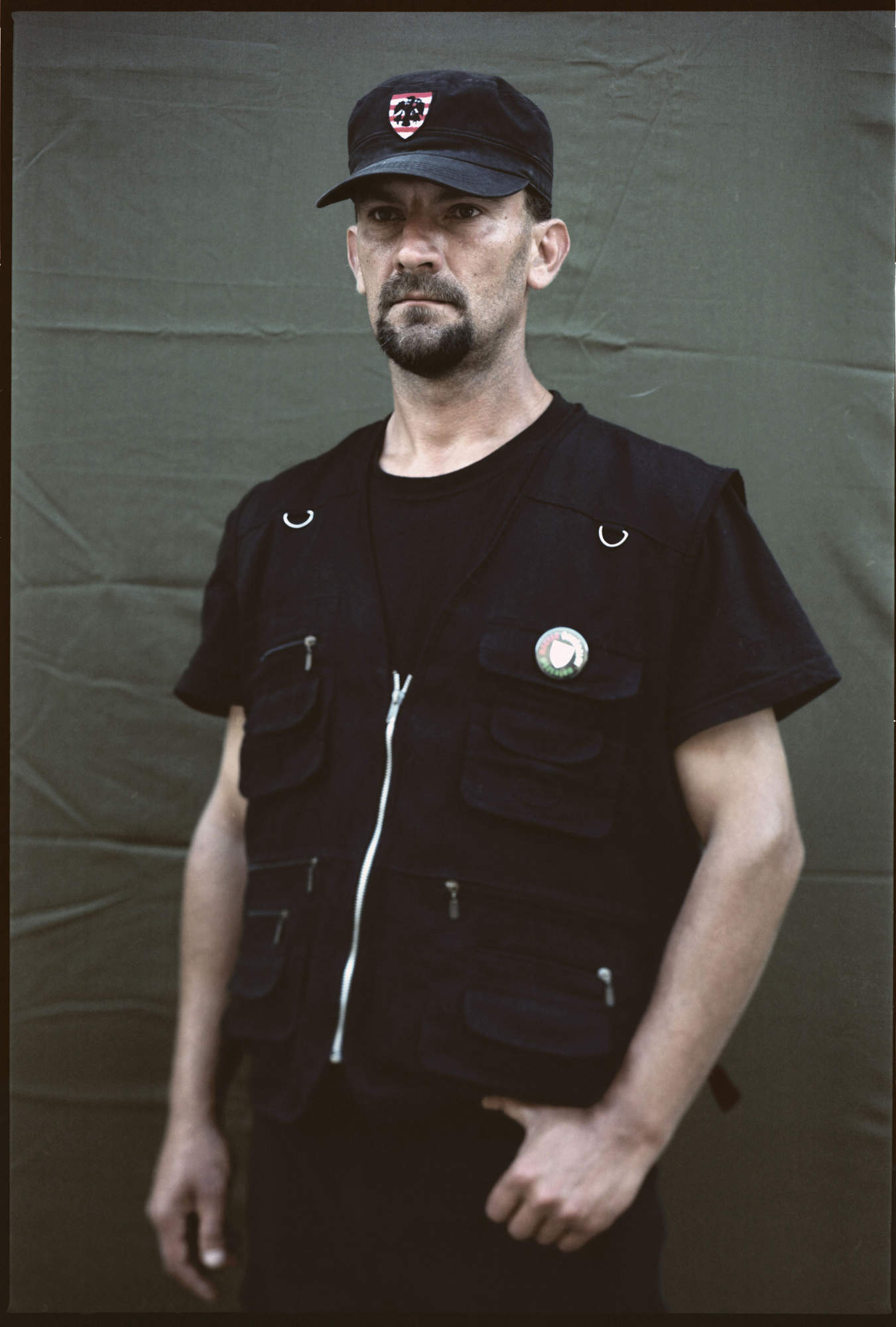

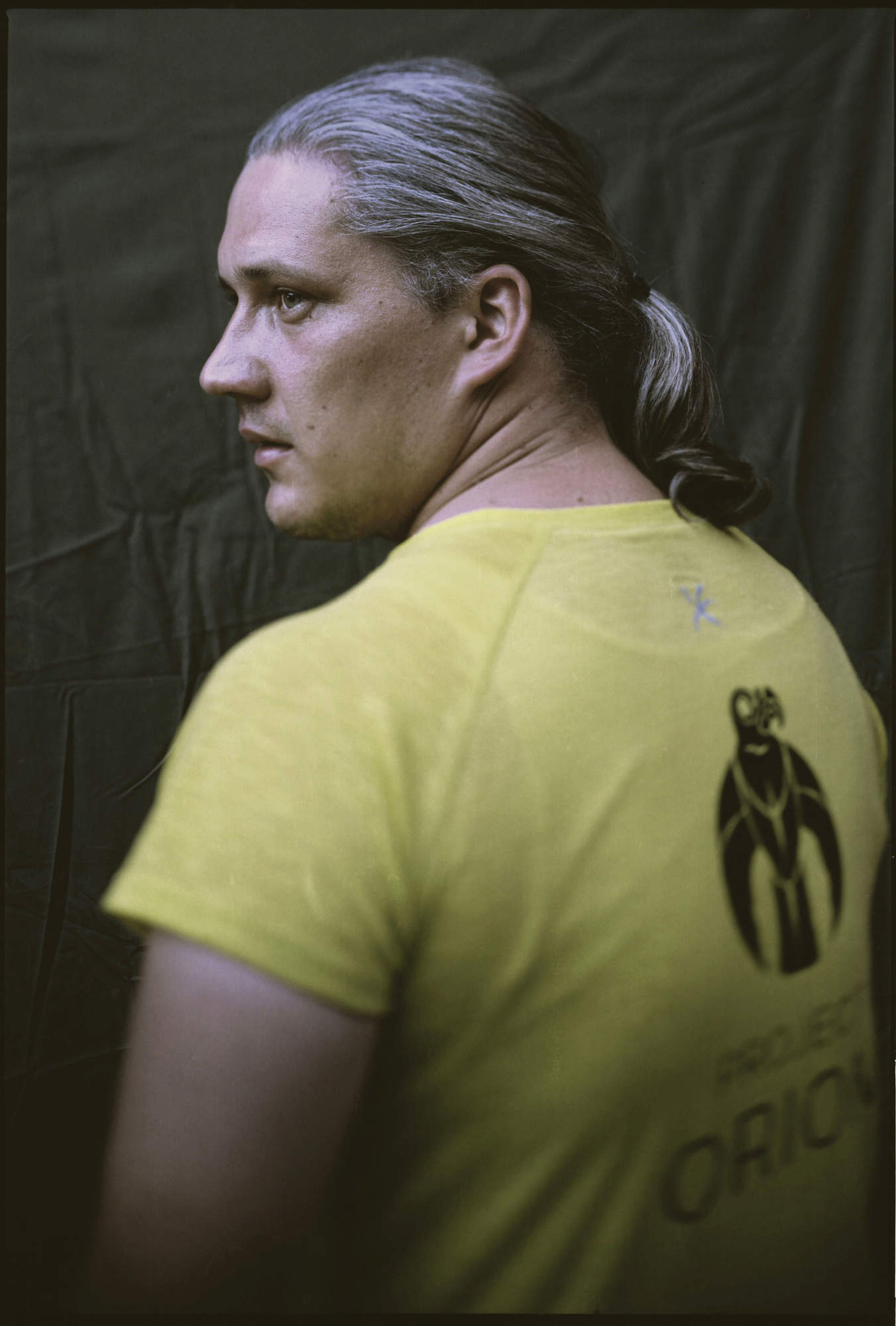

Roland (40), a regular at nationalist demonstrations.

Ferenc (41), a member of a right-wing vigilante group.

Zsolt (38), a member of a right-wing vigilante group.

Construction worker, Bence (17), a self-proclaimed neo-nazi.

Slovakia

For a small country that only gained independence from Czechoslovakia in 1993 after a brief period of autonomy as a puppet state of Nazi Germany between 1939 and 1945, Slovakia has a number of nationalist, right-wing outfits ranging from the paramilitary Slovenskí Branci to the Slovak Revival Movement and the Slovak National Party which was in a government coalition from 2006 to 2010. More recently, however, another party – the People’s Party-Our Slovakia – has set alarm bells ringing both within Slovakia and amongst fellow members of the EU after taking over 8% of the vote in the 2016 parliamentary elections.

Founded in 2003 and led by Marian Kotleba, the party claims to build on the legacy of Jozef Tiso, a Roman Catholic priest and Slovakia’s wartime president who collaborated with Nazi Germany and was hanged for treason after the war. Kotleba’s party won the regional elections in the Banska Bystrica region and now serves as its governor. It campaigns for immigration control and the strengthening of Christian values while stridently criticising the country’s Roma minority. The party also wants to take Slovakia out of the EU, the Euro and NATO. Kotleba was feted by his supporters when he had the EU flag taken down after taking control of the Banska Bystrica townhall.

The leader of the paramilitary group Slovanski Branci, architecture student Peter Svrcek.

19 year old Barbara Bpackova, a member of the nationalist paramilitary Slovenski Branci.

A young female recruit to the nationalist paramilitary Slovenski Branci shows her identity tags while training in the forest.

Jan Doval, a member of the nationalist paramilitary group Slovenski Branci.

Russia

Right-wing, ultra-nationalist groups abound in Russia – more than 40, according to some estimates – many with their own newspapers, paramilitary training camps and public marches.

The aims and philosophies of the larger groups range from the more traditional nationalist aims espoused by parties like Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) to the more fringe groups such as the National Bolshevik Party, led by maverick Eduard Limonov, that was banned in by the Russian courts in 2007.

Other outfits, such as the Committee for Nation and Freedom (KNS) focus on martial arts and weapons training in readiness for any military threat to the ‘Russian people’ while the members of Straight Edge Father Frost Mode (PPDM) eschew drink, drugs and tobacco, extolling the virtues of a healthy lifestyle promoted by rituals such bathing in frozen lakes and rivers during the winter.

Right wing groups in Russia often vent their anger against immigrants from former Soviet Republics suspected of involvement in criminal activities, homosexuals and Jews. Under pressure from the West, with sanctions in place following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its support of the war in Eastern Ukraine, old notions of self-reliance in the face of demonisation by the outside world have been stoked by Vladimir Putin’s government keen to prop up its flagging popularity.

Ukraine

Ukraine‘s recent history has opened old fissures in the country and reignited debates about national identity that have been seized upon by various nationalist groups, some of whom have despatched volunteers to the war in the East of the country to fight against separatists and their Russian sponsors.

Ukrainian nationalists come in various guises, ranging from paramilitary groups that are actively fighting in the East of the country against separatists and Russian volunteers to mainstream political parties such as Svoboda (Freedom), founded in 1991 and often accused of being a fascist and anti-semitic organisation, a charge its leaders deny. Nationalists groups draw inspiration from anti-Soviet, nationalist leaders such as Symon Petliura who led a push for Ukrainian independence following the Russian Revolution and Stepan Bandera whose Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) temporarily collaborated with Nazi Germany to advance Ukraine’s breakaway from the Soviet Union.

Scenes from Evgenij Stojka’s life. Stojka is a self-proclaimed neo-Nazi. He says he became interested in the Nazi movement when he was 14. He lives in a small flat with his wife and daughter in Kiev.