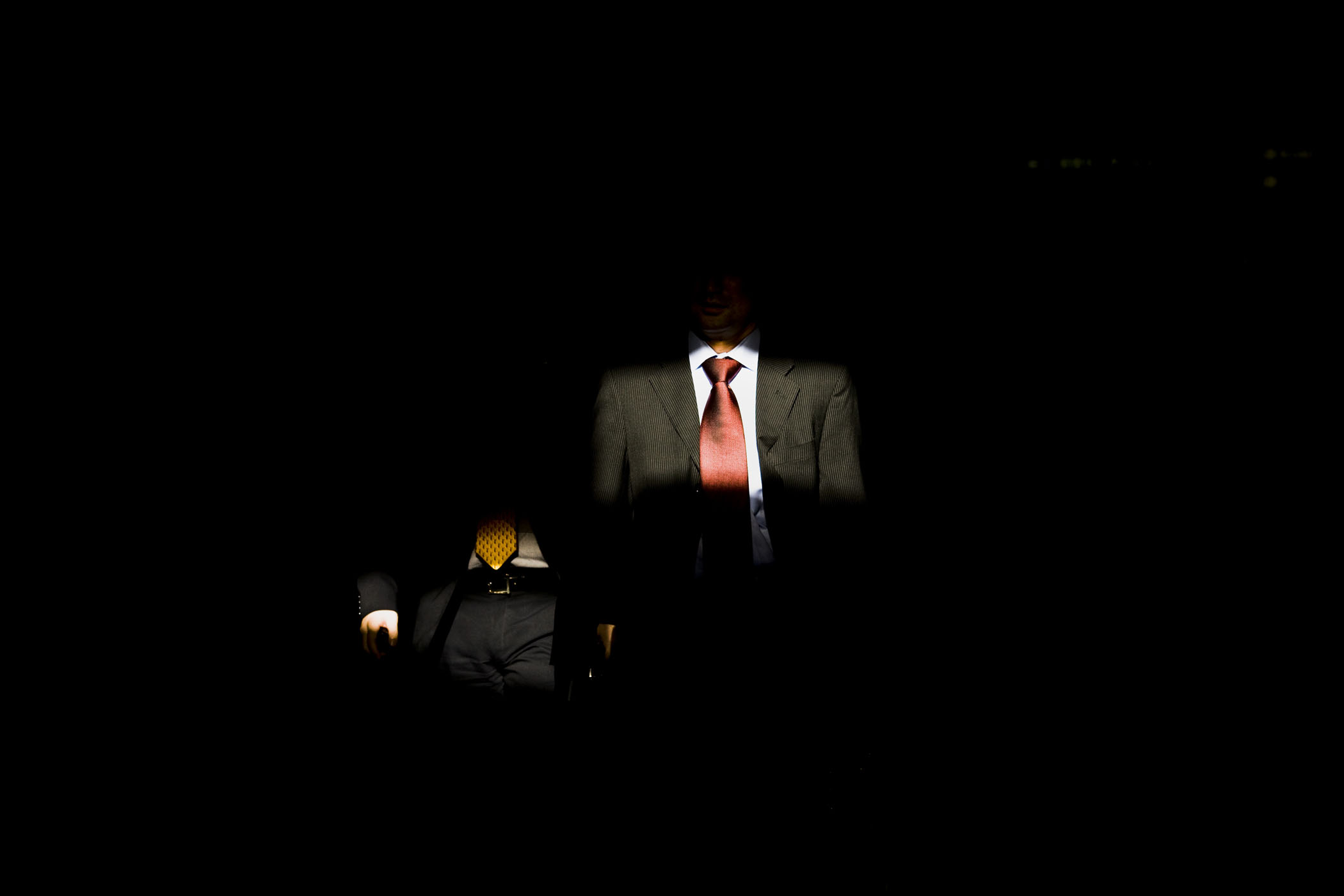

Two new words have entered the Japanese dictionary in the past decades:

karoshi

death due to brain or heart ailment caused by overwork.

karojishi

death as a result of suicide caused by depression and overwork.

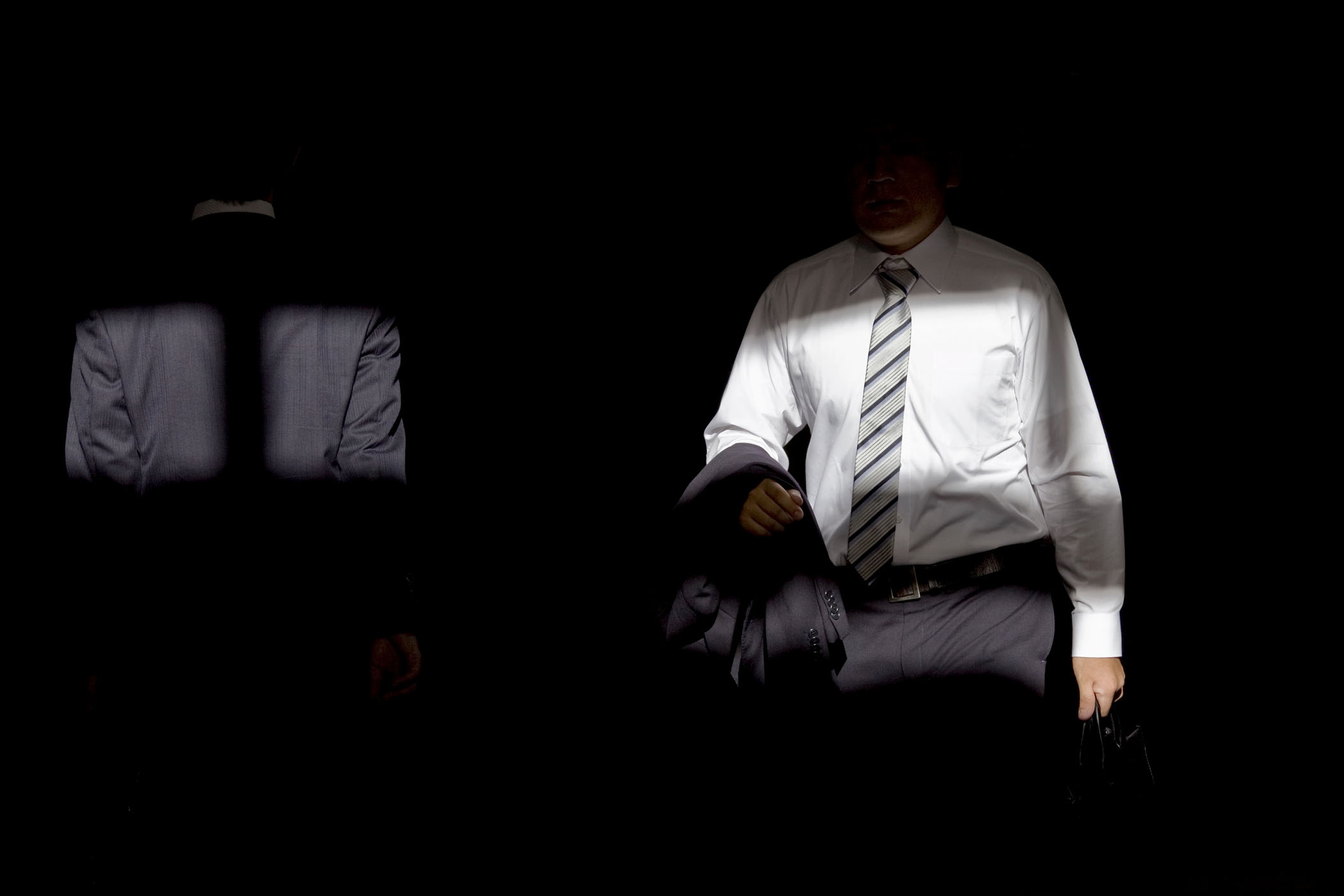

The recession of the 1990s forced many Japanese companies to rethink their employment policies, laying off tens of thousands and replacing costly full-time workers with low-paid temporary workers who have no benefits or job security. As a result, so-called ‘salarymen’ – those with longterm contracts and a level of job security – increasingly had to work longer hours for fear of losing their jobs to cheap replacements.

“Why do Japanese people work so much? The cause of my depression is definitely overwork”

Naoya Nishigaki, 27 - committed suicide by overdose on medication.

“Learning to work with depression is a true sign of professionalism.”

Naoya Nishigaki's boss

“Why do Japanese people work so much? The cause of my depression is definitely overwork” Naoya Nishigaki, 27, a systems engineer, wrote on his blog. “I can’t do anything. I don’t feel like doing anything. I just feel irritated, exhausted, and disgusted. I try to suppress these feelings with medication, but I feel like my medication has become less and less effective lately. I’m so worried. What should I do?” Naoya overdosed on his medication in 2006.

His mother Michiyo Nishigaki, 67, found out later that 13 out of 74 of his coworkers either have taken extended leaves of absence or resigned. She was surprised when her son’s boss told her, “Everybody suffers from depression here. You have to work through it with medication. Learning to work with depression is true sign of professionalism.”

The word “karoshi” came into common use around 1990, when Japanese workers died from heart attacks or strokes due to long work hours. Over the past several years, the number of suicides brought on by excessive overwork – or “karojishi” – have increased rapidly.

Syota Nakahara

Syota Nakahara, 32, a former systems engineer, has been suffering from depression caused by overwork, sleep deprivation and stress for eight years. He described his working conditions as the “death march”— excessive overwork in order to achieve unrealistic goals. He sued his company for unpaid overtime and won a lawsuit in 2006, but is still unable to return to work.

“I used to work from 8:40 a.m. to 3 a.m. for nearly two years. I was psychologically on the edge. I could not register scenery around me. I couldn’t tell what day it was or which season. The only thing I could see was the entrance to the company and the computer on my desk. I could not hear any sounds around me and my vision was really narrow and blurred. I could not even hear my boss’s voice,” he said.

Even under the harsh working conditions, he hesitated to resign. “I was afraid that once I lost my full-time job, my life would be destroyed. It is really hard to get full-time positions. With low-paid temp work, I thought I would plunge into poverty and hit the bottom of the society. That’s the end of my life.” Nonetheless, he finally quit. “I came to the point where I had to choose between life or work.”

Koichi Nanbu

Koichi Nanbu, 58, disappeared from his family home and work and traveled nearly 300 miles west to the city of Nara where he used to live with his wife over 20 years before. On the morning of 11 February 2004 he left his bag in a locker, put on a matching watch he and his wife would wear on special occasions and put a small hand-written note in his shirt pocket. At 9:34am he went to the train station from where he could see the apartment where he and his wife had lived as newlyweds and jumped in front of a train.

The note in his pocket was filled with various scribbled apologies. “I can’t work anymore. I don’t know why. I’m really sorry about causing so much trouble for the company.” Mr Nanbu was a plant engineer for a small company where his long hours kept him away from his family. Many people apologise in their suicide notes, says his widow Setsuko Nanbu, 67. “I think he knew it was wrong, but he was in so much pain that he felt like death was the only way to escape and be relieved of it.“

Mrs Nanbu says she initially could not talk about her husband’s suicide and told neighbours that he had died of a heart attack. She thought that his suicide would dishonour him. But as time went by she started to chang her mind. “I realised that my lying about how he died was like denying how he lived.” Today, she works for a non-profit organisation for suicide prevention and speaks about her husband’s suicide at conferences and events.

65 year old Setsuko Nanbu holds her late husband's husband's jacket, briefcase and watch.

65 year old Setsuko Nanbu holds her late husband's husband's jacket, briefcase and watch.

Masayoshi Shimamura

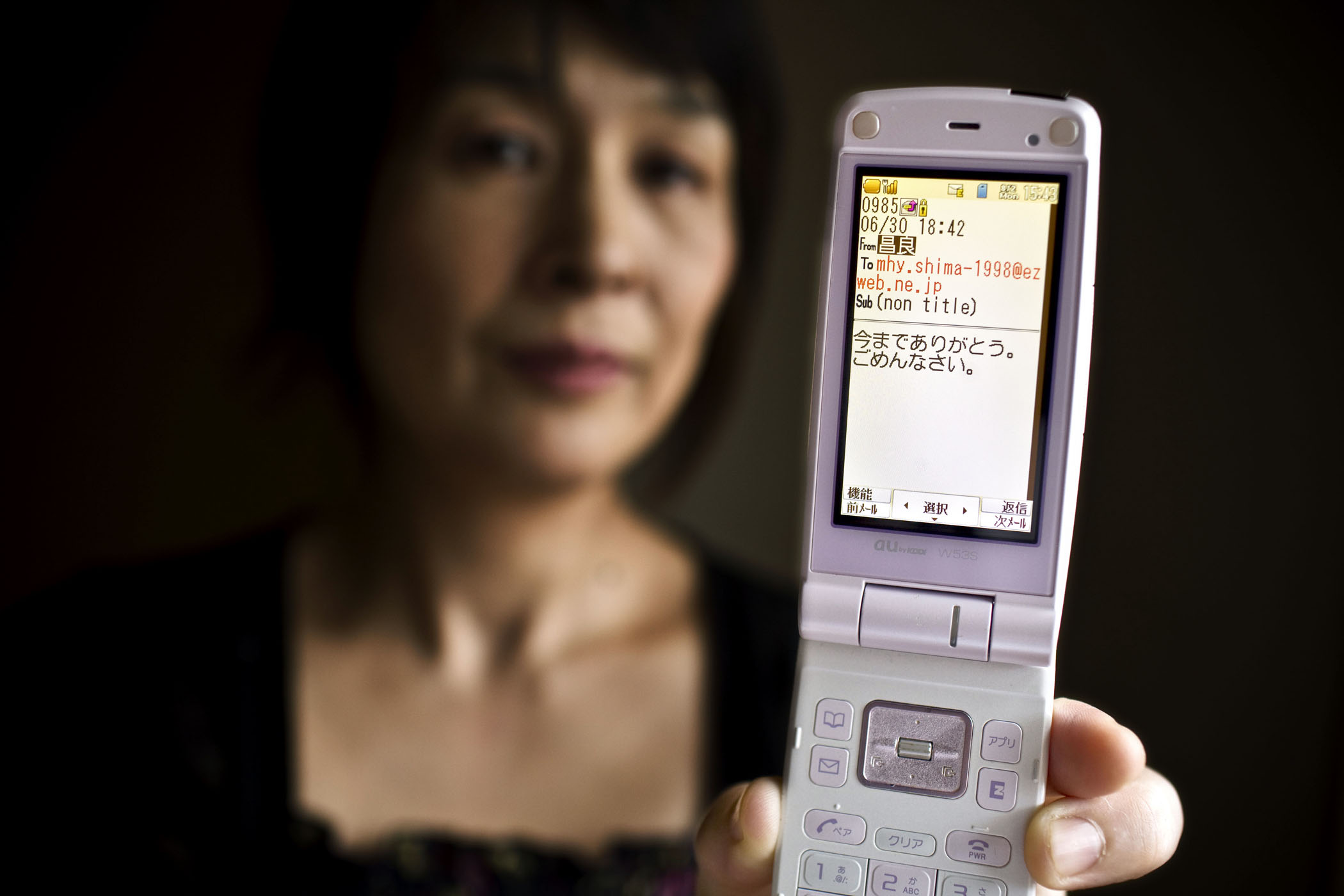

In an attempt to hide their violation of labour laws on working hours or harassment some companies accuse the deceased of causing financial damage to the company. Masayoshi Shimamura, worked for an automobile company as a salesman for 26 years. He battled with depression for six years but ultimately took his own life due to the pressures of work.

When his wife Hideko Shimamura, 50, called his company about his suicide two of his bosses immediately visited her and asked her whether he had said anything about the company or left a note or a diary. She suspects that their curiosity was because one of his bosses had been bullying him. The company declared that it would not be paying his retirement benefits as he had “caused damage to the company” and his former bosses threatened to sue his widow. “It was really cruel for them to threaten us with a penalty. We had just lost a loved one and had no idea how to survive from one day to the next” she says.

48 year old Hideko Shimamura shows the last email from her late husband on her mobile phone.

Hideko and Masayoshi Shimamura's wedding rings.

Isolation, survivor’s guilt and regret are just the tip of the iceberg for many of the bereaved family members. After a husband’s suicide a mother may be left with small children and debts. If he had jumped onto a train track, a train company can demand a fine for disruption of service. If he jumped from a building, the building management often charges a “cleaning fee”. Very few of the bereaved ever file compensation claims against companies. The majority of widows are overwhelmed by the financial difficulty of losing their sole bread winner. Most can barely afford their daily expenses, let alone pay for legal fees.

Japan has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. More than 30,000 people a year on average have taken their own lives since 1997. Still, the stigma associated with suicide remains strong and many family members can’t speak about their loved one’s suicide for fear of being ostracised from their communities.

The Last Conversation

The widows of men who have committed suicide due to overwork and work-related stress tell of the last conversations they had with their husbands.